Thrombocytopenia is when you have too few platelets in your blood. This can cause bleeding problems. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a type in which your immune system attacks and destroys platelets by mistake. What is the first line treatment for thrombocytopenia? Understand the ITP medical abbreviation and the crucial, powerful first line treatments for this condition.

The first treatment for ITP is corticosteroids. They help stop the immune system from attacking platelets. This increases the platelet count. The ASH guidelines say corticosteroids should be the first treatment for ITP.

Prednisone and dexamethasone are often used corticosteroids. New guidelines suggest a short steroid course. This is safer and works just as well.

Key Takeaways

- Corticosteroids are the recommended first-line treatment for ITP.

- Prednisone and dexamethasone are commonly used corticosteroids.

- A short course of steroids is preferred for its safety profile.

- The goal is to increase platelet counts and reduce bleeding risks.

- ASH guidelines support the use of corticosteroids as initial therapy.

Understanding ITP Medical Abbreviation and Thrombocytopenia Basics

It’s important to understand thrombocytopenia and one of its main types, known by theITP medical abbreviationImmune Thrombocytopenia(ITP). Thrombocytopenia means your blood has fewer platelets than it should. ITP happens when your immune system attacks platelets.

Definition and Classification of Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is when your platelet count is under 150 × 10^9/L. It’s divided into types based on why it happens. Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) is when your immune system destroys platelets.

What Does ITP Stand For?

ITP means Immune Thrombocytopenia. It’s when your immune system attacks and destroys platelets. This makes it hard for your blood to clot, raising the risk of bleeding.

Epidemiology and Incidence Rates

ITP is a rare condition, affecting 2 to 5 people per 100,000 each year. It can happen to anyone, but how it’s treated changes with age. Knowing about ITP helps doctors treat it better.

Pathophysiology of Immune Thrombocytopenia

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a complex autoimmune disorder. It causes low platelet counts because of immune attacks and poor production. This condition, also known as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, happens when the body attacks its own platelets.

Autoimmune Mechanisms in ITP

The autoimmune nature of ITP involves antibodies against platelets. These antibodies mark platelets for destruction, mainly in the spleen. There, immune cells destroy the antibody-coated platelets. This greatly lowers the platelet count, causing ITP symptoms.

ITP’s autoimmune mechanisms are complex. Autoantibodies against platelet surface glycoproteins are a key factor. These autoantibodies can destroy platelets in several ways, including complement activation and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis.

Platelet Destruction Processes

Platelet destruction in ITP mainly happens in the spleen. The spleen is where antibody production and platelet removal occur. The spleen’s role is critical in ITP’s pathophysiology, as it’s the main site of platelet destruction.

Other mechanisms, like complement activation and cytotoxic T cells, also play a role in platelet destruction. Knowing these processes helps in finding effective treatments.

Role of Impaired Platelet Production

While platelet destruction is a key feature of ITP, impaired production also plays a big part. Autoantibodies can target megakaryocytes, the bone marrow cells that make platelets. This reduces platelet output.

The bone marrow’s ability to make more platelets to replace those destroyed is often impaired in ITP. This makes the thrombocytopenia worse in patients.

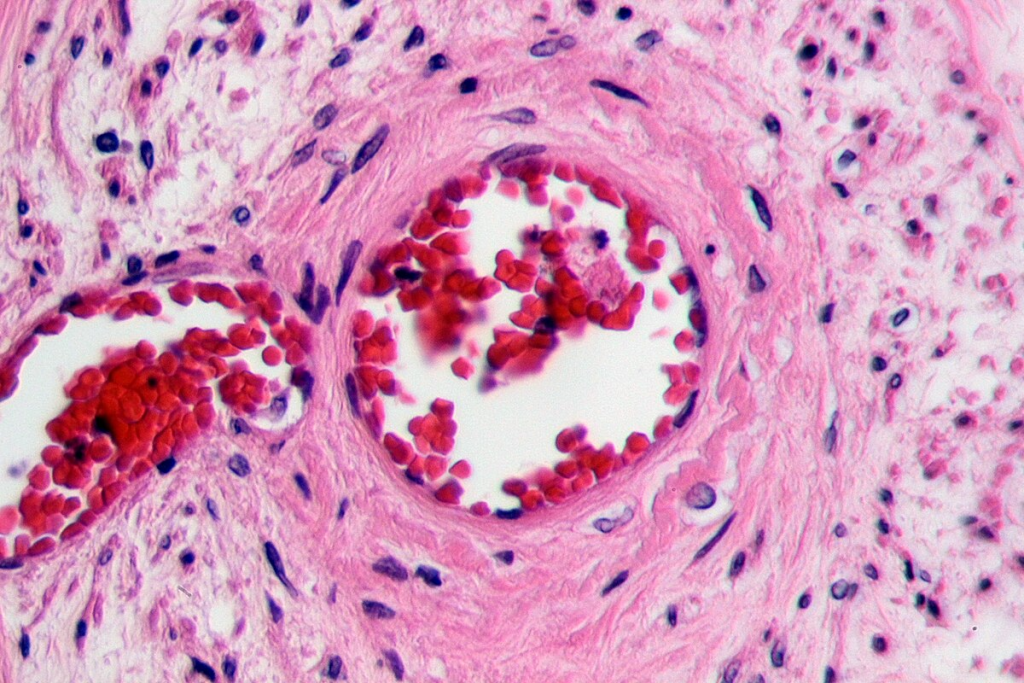

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia

Diagnosing thrombocytopenia involves both clinical signs and lab tests. People with thrombocytopenia might show signs like petechiae, purpura, or mucosal bleeding. It’s key to look for any underlying causes or factors.

Common Signs and Symptoms

Signs include easy bruising and bleeding that doesn’t stop. Some people might not show any symptoms but are found to have it during blood tests.

Doctors say the symptoms of ITP can range from mild to severe. It helps in treating the condition effectively.

Diagnostic Approach and Criteria

To diagnose thrombocytopenia, other causes of low platelets are ruled out. A detailed medical history and physical exam are key.

- Looking for signs of bleeding or bruising

- Checking medication history for possible causes

- Checking for underlying conditions that might cause thrombocytopenia

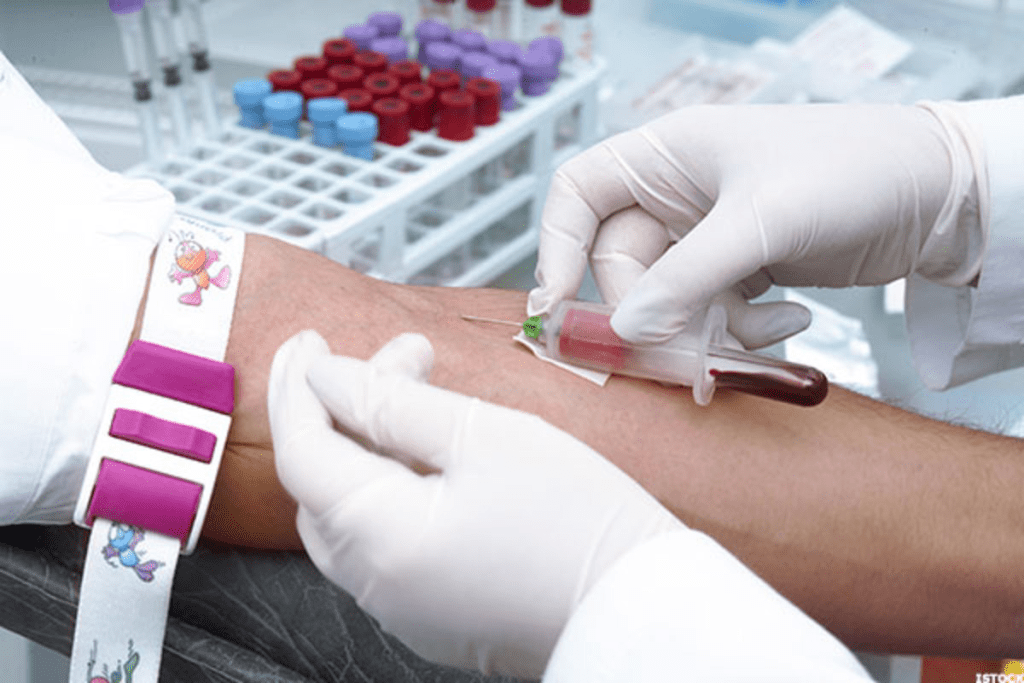

Laboratory Evaluation and Testing

Labs play a big role in diagnosing thrombocytopenia. A complete blood count (CBC) is usually the first test. It checks the platelet count. Other tests might include:

- Peripheral blood smear to look at the platelet shape

- Bone marrow exam in some cases to check platelet production

- Tests to rule out other causes, like infections or autoimmune disorders

By using both clinical evaluation and lab tests, doctors can accurately diagnose thrombocytopenia. This helps in creating the right treatment plan.

Corticosteroids as First-Line Treatment for Thrombocytopenia

In treating ITP, corticosteroids are key. Corticosteroids help by reducing how the immune system attacks platelets. They might also help make more platelets.

Prednisone Therapy

Prednisone is often given at 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg/day. This dose helps many patients by raising their platelet counts. The flexibility in dosing lets doctors adjust treatment for each patient.

Dexamethasone Protocols

Dexamethasone is given at 40 mg/day for 4 days as an alternative. This shorter treatment is good for some patients. Dexamethasone is a quick option for starting treatment.

Mechanism of Action in ITP

Corticosteroids reduce platelet destruction and might boost platelet production. Knowing how they work shows why they’re a top choice for starting treatment.

Optimal Duration of Steroid Treatment

How long to use corticosteroids has been debated. New guidelines say a short course (≤6 weeks) works well and has fewer side effects. This way, patients get the benefits without long-term steroid use.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) in Thrombocytopenia Management

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a helpful treatment for patients with thrombocytopenia. It’s great when you need platelets to come back fast. It works best in severe cases or when you need platelets quickly before surgery.

Clinical Indications for IVIG Use

IVIG is best for those with severe thrombocytopenia or who need platelets quickly. Doctors decide to use IVIG based on how bad the symptoms are and the risk of bleeding.

- Severe thrombocytopenia with significant bleeding risks

- Need for rapid platelet count increase before surgical procedures

- Patients are unresponsive to first-line treatments like corticosteroids

Dosing Strategies and Administration

For IVIG, doctors usually give 1 g/kg/day for 1 to 2 days. The exact amount and time can change based on how the patient responds and their health.

Key considerations for IVIG administration include:

- Monitoring the patient’s vital signs during infusion

- Adjusting the infusion rate based on patient tolerance

- Pre-medication to prevent infusion-related reactions

Efficacy Compared to Corticosteroids

IVIG can quickly raise platelet counts, but how well it works compared to steroids varies. It’s often used with steroids or as an alternative for those not responding to steroids. The choice between IVIG and steroids depends on the situation, the patient, and the treatment goals.

Potential Adverse Effects

IVIG is usually safe, but side effects can happen. These might include reactions during infusion, headaches, and, rarely, blood clots.

Common adverse effects to monitor:

- Infusion-related reactions (fever, chills)

- Headache and fatigue

- Rare but serious risks like thromboembolic events

Evaluating Treatment Response in ITP Patients

Checking how ITP patients react to treatment is key. It helps doctors decide if the treatment should stay the same or change.

International Working Group Response Criteria

The International Working Group set up rules for checking treatment results in ITP patients. These rules help doctors see if treatments work and talk about them easily.

Complete Response (≥100 ×10^9/L)

A complete response means the platelet count goes up to ≥100 ×10^9/L. This shows the treatment is working well and the patient is getting better.

Partial Response (≥30 ×10^9/L and at least double baseline)

A partial response is when the platelet count hits ≥30 ×10^9/L and is at least double the starting count. This shows the treatment is helping, even if the platelet count isn’t back to normal.

Monitoring Protocols During Treatment

It’s important to keep checking platelet counts and how the patient is feeling during treatment. This helps see if the treatment is working and if it needs to be changed.

We keep a close eye on our patients’ treatment results. We adjust the treatment as needed to get the best results. Using the International Working Group’s rules helps us make sure we’re doing the right thing for our patients.

Management of Refractory or Persistent Thrombocytopenia

When first treatments for ITP don’t work, doctors look for other options. Patients with hard-to-treat thrombocytopenia need a detailed treatment plan. This plan should meet their specific needs.

Second-Line Treatment Options

For those who don’t get better with corticosteroids or IVIG, second-line treatments are key. These treatments target specific ways ITP works.

Rituximab and Other Immunomodulators

Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is often used next. It helps by getting rid of B cells, which makes fewer autoantibodies against platelets. The ASH-ITP Guidelines say rituximab can help some patients with hard-to-treat ITP.

Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) like eltrombopag and romiplostim help make more platelets. They are good for managing hard-to-treat ITP. These drugs aim to boost platelet counts in a targeted way.

Surgical Interventions: Splenectomy Considerations

Splenectomy, or taking out the spleen, is another choice for hard-to-treat ITP. The spleen destroys a lot of platelets. Taking it out might raise platelet counts. But this choice should be thought over carefully, weighing the risks and benefits.

We mix different treatments to manage hard-to-treat thrombocytopenia well. The right treatment depends on the patient’s situation and how they’ve reacted to other therapies.

Special Patient Populations with Thrombocytopenia

Managing thrombocytopenia in special groups like pregnant women and children is challenging. We need to tailor our care to meet their specific needs.

Pregnancy-Associated ITP Management

Pregnancy with ITP needs careful handling to protect both mom and baby. Close monitoring is key to avoiding pregnancy and delivery issues. Guidelines stress the importance of teamwork between obstetricians and hematologists.

We usually start with a cautious approach. We treat only when platelet counts are very low. This helps prevent bleeding, which is a big risk during delivery.

Pediatric Thrombocytopenia Approach

Kids with ITP often get better on their own. Observation is the first step, with treatment for severe cases or when they bleed.

For treatment, we might use corticosteroids or IVIG. The choice depends on how sick the child is and their overall health.

Geriatric Considerations

Older adults with ITP face extra challenges due to other health issues and medicines. We must weigh the risks and benefits of treatments carefully. This ensures the treatment is safe and effective for them.

“Geriatric patients with ITP require a thorough evaluation to find the best treatment,” say experts.

Emergency Management of Severe Bleeding

Severe bleeding needs quick action, often with IVIG and platelet transfusions. We aim to stabilize the patient and prevent more harm.

- Give IVIG to quickly boost platelet levels.

- Use platelet transfusions for severe bleeding.

- Keep a close eye on the patient for any signs of improvement or problems.

Managing thrombocytopenia in special groups requires a personalized approach. We must consider each person’s unique situation and needs.

Conclusion

We’ve looked into immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), a condition with low platelet counts. Managing ITP involves several steps. First, treatments like corticosteroids and IVIG are used. Then, we check how well these treatments work and consider other options for those who don’t respond well.

New research and guidelines are changing how we manage ITP. It’s key to understand the condition’s causes, symptoms, and how to diagnose it. As we learn more, we’ll have more ways to help people with ITP.

Healthcare teams should take a detailed approach to treating ITP. This can lead to better results and a better life for patients. We also stress the need for more research and treatment plans tailored to each patient’s needs.

FAQ’s:

What is Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP)?

ITP is a condition where the immune system attacks and destroys platelets. This leads to a low platelet count. It can cause bleeding problems.

What are the first-line treatments for ITP?

The first treatment for ITP is corticosteroids like prednisone and dexamethasone. They help the immune system stop attacking platelets. This increases the platelet count.

How do corticosteroids work in treating ITP?

Corticosteroids reduce the immune system’s attack on platelets. They might also help increase platelet production. This helps raise the platelet count.

What is the optimal duration of steroid treatment for ITP?

New guidelines suggest a short steroid treatment (≤6 weeks) is best. It’s as effective as longer treatment but has fewer side effects.

When is Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) used in ITP management?

IVIG is used for severe thrombocytopenia or when a quick increase in platelet count is needed. It blocks the spleen’s Fc receptors, reducing platelet destruction.

How is treatment response evaluated in ITP patients?

Treatment success is judged by the International Working Group’s criteria. A complete response is a platelet count of ≥100 ×10^9/L. A partial response is ≥30 ×10^9/L and at least double the baseline count, without bleeding.

What are the second-line treatment options for ITP?

Second-line treatments include rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, and thrombopoietin receptor agonists like eltrombopag and romiplostim. Splenectomy, the removal of the spleen, is also an option.

How is ITP managed in special populations?

Managing ITP in special groups like pregnant women, children, and the elderly requires careful consideration. Treatment must be adjusted as needed to ensure safety and effectiveness.

What is the incidence of ITP?

ITP is rare, affecting 2 to 5 per 100,000 people yearly. It can happen in both children and adults.

How is ITP diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a clinical evaluation and lab tests. A complete blood count (CBC) checks the platelet count. A peripheral blood smear examines platelet shape and rules out other conditions.

References

- Arnold, D. M., et al. (2017). Management of newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Advances, 1(20), 2069-2077.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5737126/

- Cuker, A. (2021). Corticosteroid overuse in adults with immune thrombocytopenia. Current Opinion in Hematology, 28(5), 379-386.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2475037922014509