Restrictive airway disease in children refers to a pattern of breathing difficulty that occurs when the lungs or chest wall limit full expansion, so the child cannot take a deep breath as easily as usual. This restrictive lung physiology reduces lung volumes and can make everyday activities, sleep, and play more tiring or difficult.

LivHospital provides pediatric respiratory care for people from around the world. Reactive airway disease (RAD) is a non‑specific term sometimes used when children have asthma‑like symptoms such as coughing and wheezing but a clear diagnosis has not yet been established; clinicians may use it as a provisional label while they run tests and monitor symptoms.

Key Takeaways

- Restrictive airway disease (restrictive lung physiology) limits lung expansion and reduces lung volumes in children.

- Reduced lung volumes can cause shortness of breath, exercise limitation, and disrupted sleep.

- Reactive airway disease (RAD) is an umbrella term for asthma‑like wheeze and cough used during early evaluation.

- Early recognition of causes, symptoms, and appropriate tests helps guide treatment and improve outcomes.

- Specialized pediatric respiratory teams can coordinate care for international patients and families seeking a second opinion.

Understanding Restrictive Airway Disease in Children

Understanding restrictive airway disease helps parents and clinicians recognize problems with a child’s breathing early. In many cases this describes restrictive lung physiology — when the lungs or chest wall limit full expansion — which lowers lung volumes and can affect growth, activity, and overall health.

Definition and Basic Characteristics

“Restrictive airway disease” is often used in lay descriptions, but clinicians more commonly refer to restrictive lung disease or restrictive physiology. The hallmark is reduced total lung capacity and other measures on lung function testing. Spirometry and tests that measure lung volumes are used to identify a restrictive pattern and guide further evaluation.

Some population studies report that a minority of children show features consistent with restrictive physiology; prevalence estimates vary by setting and cause, so cite local or study-specific data when possible. Many children with mild restrictive findings experience improvement over time, particularly when underlying causes are treatable — early detection and tailored follow-up matter for long-term outcomes.

Prevalence and Statistics

Reported prevalence of restrictive patterns in pediatric populations varies widely depending on how studies define restrictive physiology and the populations they examine. Where available, use study citations to back any specific percentage (for example, community vs. clinic-based samples). Clinicians should interpret prevalence figures in context and counsel families that prognosis depends on the underlying cause.

Because some causes are congenital or progressive while others are transient (post-infectious or related to growth/nutrition), many children may show improvement in lung function with appropriate care and as they mature; others require long-term monitoring and management.

How It Differs from Obstructive Airway Diseases

Knowing the difference between restrictive and obstructive conditions is essential for correct management. In obstructive conditions like asthma, the problem is narrowed or inflamed airways that limit airflow — often producing wheeze and a helpful response to bronchodilators. By contrast, restrictive disease reduces lung volumes without primary airway narrowing; the lungs cannot expand fully due to issues in the lung tissue, chest wall, or supporting muscles.

Asthma and reactive airway disease are distinct concepts: asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disorder characterized by variable airflow obstruction and airway hyperresponsiveness, while reactive airway disease is sometimes used as a provisional label when asthma‑like symptoms occur but a definitive diagnosis is pending. Accurately identifying whether symptoms reflect airway inflammation versus restriction determines appropriate tests and treatments.

For clarity in patient-facing content, prefer the terms “restrictive lung disease” or “restrictive physiology” and explain any less-precise terms used in clinical practice. Where appropriate, include examples of common causes (chest wall disorders, neuromuscular disease, interstitial lung disease) and note that each cause has different implications for prognosis and therapy.

(Suggested internal links for the rewrite: spirometry glossary, pediatric pulmonology services, differences between obstructive vs restrictive lung disease.)

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Multiple factors can contribute to restrictive lung physiology in children. Understanding these helps clinicians identify an underlying cause, tailor testing, and give parents practical steps to reduce risk where possible.

Low BMI and Underweight Concerns

A persistently low weight or low BMI can be associated with poorer lung growth and reduced respiratory muscle strength, which may worsen restrictive patterns. Addressing nutrition and growth with a pediatrician or dietitian can support lung development and overall health.

Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy

Maternal smoking and significant prenatal smoke exposure are linked to altered lung development and lower lung function in childhood. Avoiding tobacco and secondhand smoke during pregnancy and after birth is a key prevention strategy to protect developing lungs and reduce the chance of later breathing problems.

Underlying Health Conditions

Certain medical conditions can cause restrictive physiology because they affect lung tissue, the chest wall, or the muscles that power breathing. Examples include congenital chest wall disorders (for example, severe scoliosis), neuromuscular diseases (such as muscular dystrophy), and interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis. These are distinct from airway conditions like asthma, which primarily involve inflamed, narrowed airways.

Other contributors include significant early-life respiratory infections (for example, severe bronchiolitis or pneumonia) that may impact lung growth, environmental exposures (prolonged secondhand smoke, indoor air pollutants), and, in some studies, lack of breastfeeding as an associated factor — associations vary by study and do not always prove causation.

Allergic conditions and repeated allergic reactions (including severe allergies or allergic reaction to inhaled triggers) more commonly produce obstructive symptoms like wheeze, but they can coexist with or complicate restrictive conditions; careful clinical assessment distinguishes the predominant problem.

Practical prevention and next steps

- Encourage smoke‑free environments: pregnant people and household members should avoid smoking and secondhand air.

- Promote good nutrition and monitor growth; refer to pediatric nutrition if BMI is low.

- Keep up to date with routine vaccinations to lower risk of severe respiratory infection.

- If a child has recurrent breathing problems or poor growth, ask the pediatrician about further evaluation (lung function tests, imaging, or referral to a pediatric pulmonologist).

Recognizing Wheezing and Other Symptoms

Early recognition of wheezing and related signs helps families get the right care sooner. Wheeze is a common audible clue that something is affecting a child’s breathing, but not all breathing problems sound the same—knowing what to listen and look for improves triage and outcomes.

Characteristic Breathing Patterns

Children with airway problems may make a high-pitched wheezing or whistling sound when they breathe out, especially during activity or at night. Parents often describe it as a noise that can sound like a whistle or a faint musical tone. In some cases, wheezing may be intermittent and triggered by infections, exercise, or allergens.

Other breathing changes include faster breathing, shallow breaths, or a feeling that the child “can’t catch their breath.” Watch for breathing that seems labored or uneven—these are important cues to seek evaluation.

Physical Signs to Watch For

Look beyond the sound: physical signs that suggest more serious breathing difficulty include

- retractions (skin pulling in around the ribs or neck with each breath)

- fast breathing or unusually slow breathing

- nasal flaring or use of neck and chest muscles to breathe

- pale or bluish lips/face (cyanosis)

- poor feeding, decreased urine output, or extreme drowsiness in infants

Common accompanying symptoms include cough, chest tightness, or a prolonged cough after a respiratory infection.

Behavioral Changes in Children

Reduced energy, refusal to play, increased fussiness, or becoming unusually tired during or after activity are important behavioral clues that a child’s breathing is affected. Parents may notice sleep disturbance or nighttime coughing that wakes the child.

When to Seek Medical Attention

If a child has persistent or recurrent wheezing, frequent coughing, or ongoing trouble breathing, seek prompt medical evaluation — early assessment can change the course of treatment and improve outcomes. For urgent or emergency signs (call emergency services or go to the nearest ER):

- severe difficulty breathing, gasping, or inability to speak or feed

- blue or gray lips/face

- markedly reduced consciousness, extreme sleepiness, or poor responsiveness

- severe retractions or very fast breathing

For non-emergency but concerning symptoms, contact your pediatrician. Primary care can often triage: if symptoms are mild and stable they may recommend home measures, controller treatment trials, or a referral. If symptoms are severe, worsening, or unclear, your pediatrician may refer you to a pediatric pulmonologist or recommend immediate evaluation.

How to Describe Symptoms to Clinicians

When you call or see a clinician, describe:

- When the wheeze or cough started and how often it happens

- what the wheezing sound is like (whistling, musical, constant or intermittent)

- What seems to trigger it (exercise, cold air, infections, foods, or allergens)

- any red-flag signs (difficulty feeding, blue lips, very fast breathing)

You can mention whether symptoms improve with a brief bronchodilator or inhaler (if previously tried) — clinicians may ask whether the child has used a rescue inhaler and whether it helped.

At-Home Steps and Exercises

While awaiting evaluation, keep the child calm, maintain a smoke‑free environment, and ensure they get adequate fluids and rest. In older children with a known diagnosis, clinician‑recommended breathing exercises and pulmonary physiotherapy can help improve ventilation and comfort — ask for specific instructions from a pediatric respiratory therapist.

If you notice any emergency signs above, seek immediate care. Otherwise, schedule an appointment with your pediatrician and be prepared to request lung function tests or a referral to a specialist if symptoms persist or recur.

Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches

Evaluation and management of restrictive lung physiology in children require a stepwise, multidisciplinary approach. Specialized pediatric respiratory clinics and pediatric pulmonology teams coordinate evaluation, establish the underlying cause, and design individualized treatment and follow‑up plans.

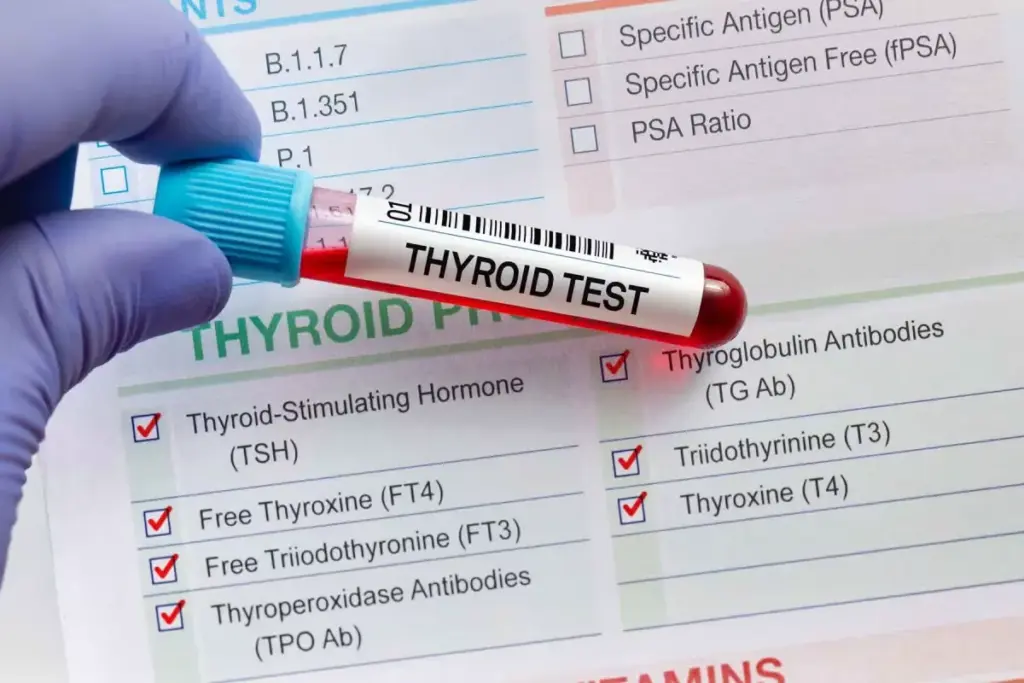

Common Diagnostic Methods

Diagnosis begins with a careful clinical history and physical exam to distinguish restrictive patterns from obstructive airways disease, such as asthma. Objective testing commonly includes:

- Spirometry with flow‑volume curves (useful first-line test; may suggest restriction but requires lung volume measurement to confirm)

- Lung volume measurement (body plethysmography or gas dilution techniques) to quantify reduced total lung capacity

- Chest imaging (X‑ray or CT) when structural lung, chest wall, or parenchymal disease is suspected

- Targeted blood tests or genetic testing if a systemic or congenital disorder is suspected

Clinicians may also review growth metrics, feeding history, and past severe infections (for example, a history of severe bronchiolitis or pneumonia) to identify contributing factors. If initial testing is inconclusive, referral to a pediatric pulmonologist for comprehensive assessment is appropriate. Accurate coding (for example, using appropriate ICD‑10 codes for the confirmed diagnosis rather than the provisional term reactive airway disease) should follow the diagnostic clarification.

Treatment Options for Children

Treatment depends on the underlying cause. Not all restrictive physiology responds to standard asthma therapies; however, some children have mixed features and clinicians may prescribe bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids when airway inflammation or reversible obstruction coexists. Typical management components include:

- Targeted medical medications as indicated — for example, short‑acting bronchodilators as a rescue inhaler for reversible obstruction, or anti‑inflammatory inhaled medicines when airway inflammation is present. Clinicians will explain whether a given inhaler is likely to help.

- Supportive measures and symptom control — oxygen support for severe cases, nutritional optimization for children with low BMI, and vaccinations to prevent severe respiratory infection.

- Non‑pharmacologic therapies — chest physiotherapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and breathing exercises or respiratory muscle training to help open airways and improve ventilation where appropriate.

Because many causes of restriction are structural or neuromuscular, management can include surgical, orthopedic, or neurology input as part of multidisciplinary care.

Innovative Treatments and Multidisciplinary Care

Specialized centers bring pulmonologists, respiratory therapists, nutritionists, and other pediatric subspecialists together to deliver coordinated care. Newer approaches focus on precision diagnosis and targeted treatments for specific underlying disorders rather than one‑size‑fits‑all therapy. In mixed obstructive‑restrictive presentations, clinicians may prescribe short trials of bronchodilators or inhaled medications to assess reversibility.

Practical steps for families: discuss a stepwise plan with your pediatrician, ask about referral for lung function tests if symptoms persist, and request a pediatric pulmonology consultation when the diagnosis is unclear or the child is not improving. Maintaining a smoke‑free environment, following immunization schedules, optimizing nutrition, and following prescribed pulmonary physiotherapy or breathing exercises are important parts of ongoing care.

Conclusion

Early recognition and appropriate care for restrictive lung physiology can meaningfully improve a child’s quality of life. This article reviewed what restrictive patterns mean, common risk factors, how they can present (including wheezing or other breathing changes), and the typical diagnostic and management steps clinicians use.

If your child has ongoing breathing concerns, discuss a clear plan with your pediatrician—ask whether spirometry or other tests are appropriate and whether a referral to a pediatric pulmonologist is needed. Treatment may include targeted medications when airway inflammation or reversible obstruction is present, plus supportive measures such as nutrition optimization, vaccinations, pulmonary physiotherapy, and home environmental changes.

Where to get help: start with your primary care provider or local pediatric clinic; they can coordinate testing, short trials of inhalers if indicated, and referrals to specialized centers or multidisciplinary teams when necessary. Early, tailored care leads to better outcomes for children and peace of mind for families.

FAQ

What is restrictive airway disease in children?

Restrictive patterns in children describe a problem with lung expansion: the lungs or chest wall limit full inhalation so total lung capacity is reduced. This leads to smaller lung volumes and can cause shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, or difficulty feeding in infants.

How does restrictive airway disease differ from obstructive airway diseases like asthma?

Obstructive diseases such as asthma primarily narrow or inflame the airways, producing wheeze and airflow limitation that often improves with bronchodilators. Restrictive physiology reduces the space the lungs can hold (reduced lung volumes) and is usually caused by problems in the lung tissue, chest wall, or respiratory muscles rather than airway narrowing.

What are the risk factors for developing restrictive airway disease in children?

Risk factors and causes include congenital or structural conditions (for example, severe scoliosis), neuromuscular disorders, interstitial lung disease, a history of severe early-life respiratory infections (such as bronchiolitis or pneumonia), prolonged exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy or childhood, and poor growth/low BMI. Associations such as not being breastfed have been reported in some studies but do not prove direct causation.

What are the common symptoms of restrictive airway disease in children?

Children may have increased work of breathing, reduced exercise tolerance, recurrent cough, or less commonly wheeze. Behavioral changes (excessive tiredness, reduced play) and poor growth may also be present. The exact symptoms depend on the underlying condition.

How is restrictive airway disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis uses clinical assessment plus lung function tests. Spirometry can suggest a restrictive pattern, but confirmation usually requires lung volume measurement (e.g., body plethysmography). Chest imaging and targeted blood or genetic tests may be needed to find the underlying cause.

What are the treatment options for restrictive airway disease in children?

Treatment targets the underlying cause and symptoms. Options include targeted medications when airway inflammation or mixed obstruction is present (clinicians may prescribe bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids in those cases), nutritional support, surgical or orthopedic interventions for structural causes, pulmonary physiotherapy and breathing exercises, and preventive measures such as vaccinations to reduce severe respiratory infections.

What is reactive airway disease, and is it related to restrictive airway disease?

Reactive airway disease (RAD) is an imprecise term often used when children have asthma‑like wheeze or cough before a definitive diagnosis. RAD and restrictive physiology describe different mechanisms and are not the same; however, a child can have mixed or evolving features that require careful evaluation.

Can restrictive airway disease be prevented?

Not all causes are preventable, but risk reduction helps. Practical steps include avoiding prenatal and secondhand smoking, ensuring good nutrition to prevent low BMI, keeping vaccinations up to date to reduce severe respiratory infections, and reducing indoor air pollutants. Early treatment of respiratory conditions can also limit long-term damage.

When should I seek emergency care for my child’s breathing?

Seek emergency care immediately for severe breathing difficulty, blue lips or face, very fast or very slow breathing, difficulty feeding or extreme drowsiness. For non‑emergency but ongoing concerns (recurrent wheezing or persistent cough), contact your pediatrician to arrange evaluation and possible referral for tests.

Where can I get specialized care for my child?

Start with your child’s primary care provider or pediatric clinic. If needed, they can refer you to a pediatric pulmonologist or a multidisciplinary respiratory center for comprehensive evaluation, diagnostic testing, and management plans tailored to your child’s condition.

References

- Martinez-Pitre, P. J. (2023, July 24). Restrictive lung disease. StatPearls.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560880/