Myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when the blood flow to the heart is severely blocked, causing damage to the heart muscle. Understanding the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction is crucial for early detection and effective treatment.

We recognize that myocardial infarction pathophysiology involves a complex series of events. Recent studies have outlined the key steps involved, including endothelial dysfunction, plaque buildup, thrombotic occlusion, ischemia, cellular necrosis, inflammation, and scar formation.

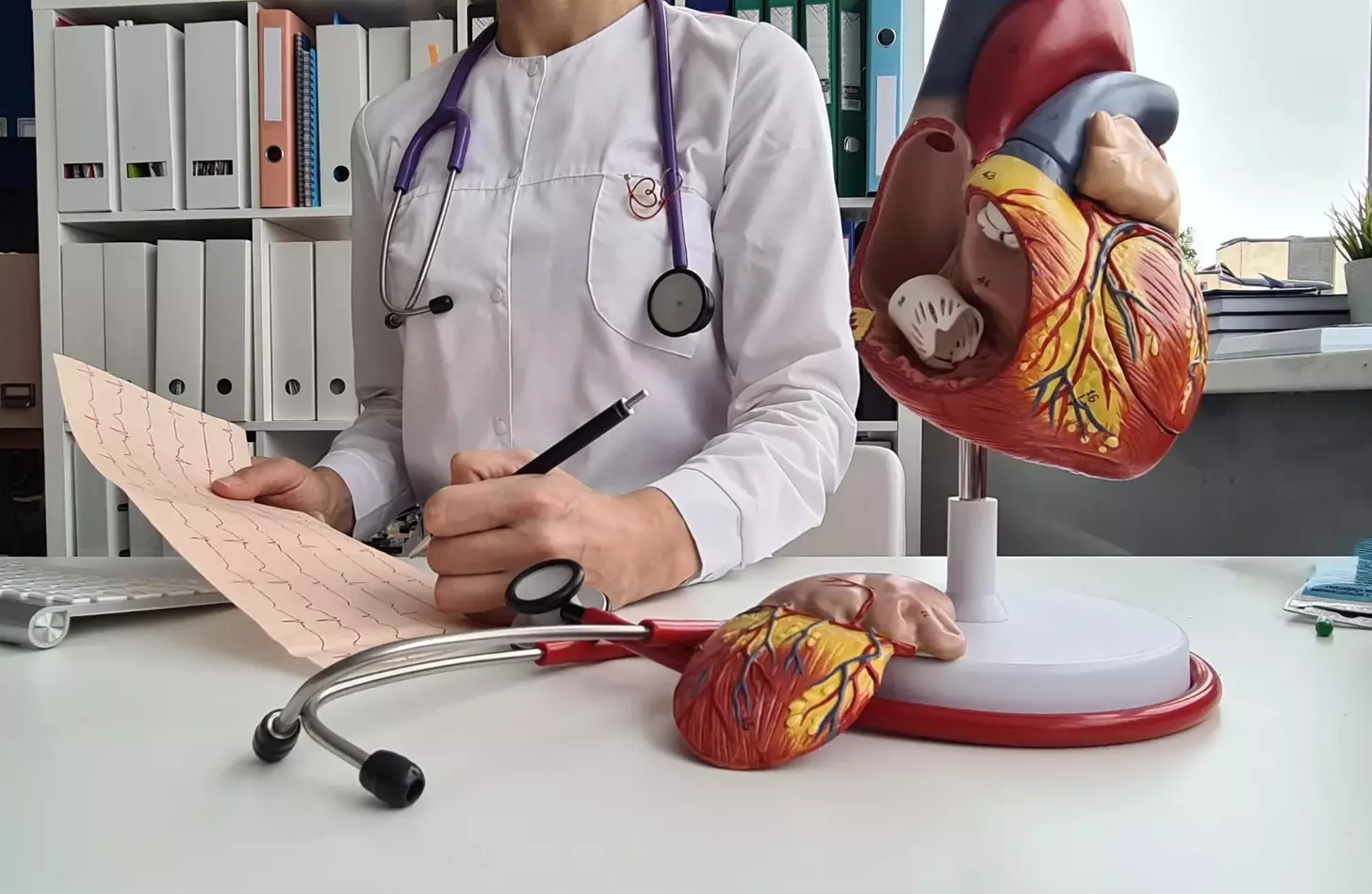

At Liv Hospital, we are committed to providing world-class cardiac care. Our team of experts is dedicated to delivering evidence-based treatments and support to patients undergoing myocardial infarction treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction is vital for early detection.

- Myocardial infarction occurs due to blocked coronary arteries.

- The primary cause is atherosclerotic plaque rupture leading to thrombus formation.

- Key steps in MI pathophysiology include endothelial dysfunction and scar formation.

- Liv Hospital provides patient-centered cardiac care.

Understanding Myocardial Infarction: Definition and Overview

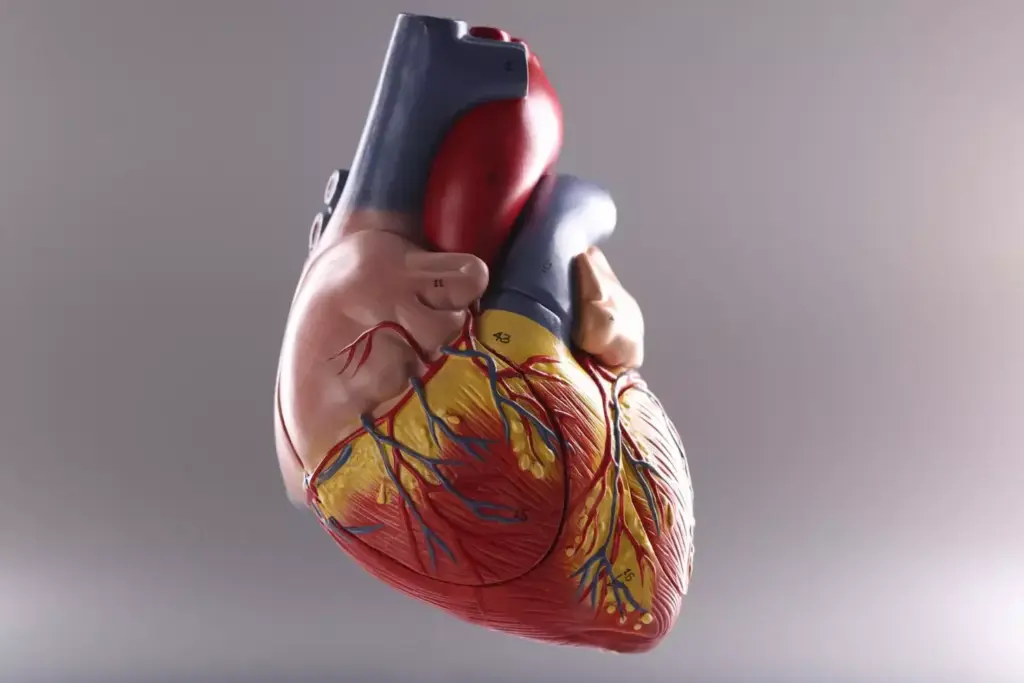

The term myocardial infarction refers to the damage caused to the heart muscle due to a lack of blood supply, often resulting from a blockage in the coronary arteries. Myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when the blood flow to the heart is obstructed, leading to heart muscle damage.

What is Myocardial Infarction?

Myocardial infarction is a serious medical condition that arises when the blood flow to the heart is severely blocked, causing damage to the heart muscle. According to the American Heart Association, MI is defined as a condition where the blood flow to the heart is obstructed, leading to heart muscle damage. This obstruction is typically caused by a blood clot that forms on a patch of atherosclerosis (plaque) inside a coronary artery.

Types of Myocardial Infarction

There are several types of myocardial infarction, classified based on the location and severity of the damage, as well as the underlying cause. The main types include:

- ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI): A STEMI occurs when a coronary artery is completely blocked, and a significant portion of the heart muscle is unable to receive blood.

- Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI): An NSTEMI occurs when a coronary artery is partially blocked, and the heart muscle is damaged, but not to the same extent as in a STEMI.

- Coronary Artery Spasm: Also known as variant or Prinzmetal’s angina, this type occurs when the coronary arteries spasm, causing a temporary reduction in blood flow to the heart.

Understanding the different types of myocardial infarction is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment and management plan.

| Type of MI | Description | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| STEMI | Complete blockage of a coronary artery | ST elevation on ECG, significant heart muscle damage |

| NSTEMI | Partial blockage of a coronary artery | No ST elevation on ECG, less severe heart muscle damage |

| Coronary Artery Spasm | Temporary spasm of a coronary artery | Temporary reduction in blood flow, often associated with variant angina |

Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Myocardial Infarction

Understanding the epidemiology of myocardial infarction is crucial for identifying risk factors and developing effective prevention strategies. Myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow to the heart is severely blocked, leading to damage or death of heart muscle tissue.

Global Burden of CAD Myocardial Infarction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major risk factor for MI, and its global burden is significant. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, with MI being a substantial contributor.

Studies have shown that the incidence of MI varies geographically, with higher rates observed in certain regions due to factors such as diet, lifestyle, and genetics. For instance, a study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology highlighted the varying incidence rates of MI across different countries.

“The global burden of cardiovascular disease is substantial, and myocardial infarction is a significant component of this burden.”

We must consider these epidemiological trends when developing strategies for MI prevention and management.

Modifiable and Non-modifiable Risk Factors

Risk factors for MI can be categorized into modifiable and non-modifiable factors. Modifiable risk factors include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and hyperlipidemia. Non-modifiable risk factors include age, gender, and family history of CAD.

| Risk Factor | Category | Impact on MI Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Modifiable | Increases risk due to vascular damage |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Modifiable | Elevates risk through metabolic dysregulation |

| Smoking | Modifiable | Significantly increases risk through vascular injury |

| Age | Non-modifiable | Risk increases with advancing age |

| Family History | Non-modifiable | Genetic predisposition to CAD and MI |

Understanding these risk factors is essential for developing targeted interventions to reduce the incidence of MI. By addressing modifiable risk factors, we can significantly impact the global burden of CAD and MI.

The Patho of MI: Foundation of Coronary Artery Disease

The pathophysiology of myocardial infarction (MI) is intricately linked with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD), primarily through the process of atherosclerosis. We will explore how atherosclerosis develops and the critical role inflammation plays in plaque formation, setting the stage for MI.

Atherosclerosis Development

Atherosclerosis is a complex process involving the accumulation of lipids, inflammatory cells, and fibrous elements in the large and medium-sized arteries. It begins with endothelial dysfunction, followed by the infiltration of lipids and inflammatory cells into the arterial wall.

Key steps in atherosclerosis development include:

- Endothelial injury and dysfunction

- Lipid accumulation and oxidation

- Inflammatory cell recruitment

- Smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation

- Extracellular matrix deposition

Role of Inflammation in Plaque Formation

Inflammation plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of atherosclerotic plaques. Inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and T lymphocytes, contribute to the destabilization of plaques, making them more susceptible to rupture.

| Inflammatory Component | Role in Atherosclerosis |

|---|---|

| Macrophages | Engulf lipids, become foam cells, and secrete inflammatory cytokines |

| T Lymphocytes | Modulate inflammatory response, influence plaque stability |

| Cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) | Promote inflammation, contribute to plaque instability |

Understanding the role of inflammation in atherosclerosis is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies to prevent MI. By targeting inflammatory pathways, we can potentially reduce the risk of plaque rupture and subsequent MI.

Step 1: Endothelial Dysfunction and Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation

The development of myocardial infarction begins with endothelial dysfunction, a critical step in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Endothelial dysfunction refers to the impaired ability of the endothelium to maintain vascular homeostasis, leading to an imbalance in vasodilation and vasoconstriction. This imbalance is often caused by various risk factors, including hypertension, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Mechanisms of Endothelial Injury

Endothelial injury can be triggered by several mechanisms, including hemodynamic stress, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress. These mechanisms can lead to the disruption of the endothelial layer, making it more susceptible to the accumulation of lipids and inflammatory cells.

- Hypertension causes hemodynamic stress, damaging the endothelial cells.

- Smoking and high cholesterol levels contribute to oxidative stress and inflammation.

- Diabetes mellitus can also impair endothelial function through various metabolic pathways.

Progression from Fatty Streak to Atherosclerotic Plaque

The progression from a fatty streak to an atherosclerotic plaque involves several stages. Initially, the accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) forms fatty streaks. Over time, these fatty streaks can evolve into more complex lesions through the recruitment of smooth muscle cells and the deposition of extracellular matrix.

- Fatty streak formation: Lipid accumulation in macrophages.

- Plaque progression: Smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation.

- Plaque complication: Calcification, ulceration, and thrombosis.

Understanding the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and the progression to atherosclerotic plaque formation is crucial for the prevention and treatment of myocardial infarction. By addressing the risk factors and utilizing appropriate therapeutic strategies, we can potentially reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events.

Step 2: Plaque Rupture and Thrombosis in MI Pathogenesis

Plaque instability leading to rupture is a key factor in the onset of myocardial infarction (MI). This critical step in the pathogenesis of MI involves the disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque, leading to the formation of a thrombus that can occlude the coronary artery.

Vulnerable Plaque Characteristics

Vulnerable plaques are atherosclerotic lesions prone to rupture. Characteristics of these plaques include a thin fibrous cap, a large lipid core, and increased inflammation. Research has shown that these features contribute to the instability of the plaque, making it more susceptible to rupture.

The thin fibrous cap is particularly significant as it is more likely to rupture under stress. The large lipid core also plays a crucial role, as it can lead to a more significant thrombus formation upon rupture.

| Characteristics | Description | Impact on Plaque Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Thin Fibrous Cap | A fibrous cap less than 65 μm thick | Increased risk of rupture |

| Large Lipid Core | A core rich in lipids and macrophages | Contributes to inflammation and instability |

| Increased Inflammation | Presence of inflammatory cells | Weakens the fibrous cap |

Mechanisms of Plaque Rupture

The mechanisms behind plaque rupture involve a complex interplay of factors, including mechanical stress and inflammation. The fibrous cap is subjected to various forces that can lead to its disruption.

Mechanical Stress: The constant pulsatile blood flow and pressure can cause fatigue and eventual rupture of the fibrous cap.

Inflammatory Processes: Inflammation within the plaque can weaken the cap by degrading the extracellular matrix and promoting apoptosis of smooth muscle cells.

Thrombotic Cascade Activation

Upon plaque rupture, the highly thrombogenic lipid core is exposed to the bloodstream, triggering the thrombotic cascade. This cascade involves the activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade, leading to thrombus formation.

The thrombus can partially or completely occlude the coronary artery, resulting in myocardial ischemia or infarction. Understanding the thrombotic cascade is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies to prevent or treat MI.

Step 3: Coronary Occlusion and Myocardial Ischemia

Coronary occlusion is a critical step in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction, leading to myocardial ischemia. When a coronary artery becomes occluded, the downstream myocardium is deprived of oxygen and nutrients, leading to cellular injury and potentially cell death.

We will explore the nuances of coronary occlusion and its impact on myocardial tissue. Understanding the differences between complete and partial occlusion, the ischemic cascade, and the wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death is crucial for grasping the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction.

Complete vs. Partial Occlusion

Coronary occlusion can be either complete or partial, each having different implications for myocardial ischemia. Complete occlusion results in severe ischemia, often leading to transmural infarction, whereas partial occlusion may cause less severe ischemia, potentially resulting in subendocardial infarction.

Complete occlusion typically occurs when a thrombus completely blocks a coronary artery. This can lead to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a condition requiring immediate medical attention.

Partial occlusion, on the other hand, may occur due to a non-occlusive thrombus or severe stenosis. This can result in non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina.

Ischemic Cascade in Myocardial Infarction Pathophysiology

The ischemic cascade refers to the series of events triggered by reduced blood flow to the myocardium. This cascade includes a sequence of metabolic, functional, and structural changes that ultimately lead to myocardial necrosis.

- Initial reduction in blood flow leads to decreased oxygen delivery.

- Cells switch to anaerobic metabolism, resulting in lactic acid accumulation.

- Contractile dysfunction occurs due to lack of ATP.

- Eventually, cell death ensues if the ischemia is not reversed.

Wavefront Phenomenon of Ischemic Cell Death

The wavefront phenomenon describes how ischemic cell death progresses from the subendocardium to the subepicardium over time. This phenomenon is crucial for understanding the temporal and spatial patterns of myocardial infarction.

Studies have shown that the severity of ischemia and the duration of occlusion determine the extent of myocardial damage. Early reperfusion can significantly limit the infarct size by salvaging the ischemic myocardium at risk.

Step 4: Cellular Response to Ischemia and Myocardial Injury

Myocardial infarction triggers a complex cellular response to ischemia, which is pivotal in the progression of myocardial injury. When the heart muscle is subjected to ischemia, a series of metabolic changes are initiated that can lead to cellular injury.

Metabolic Changes During Ischemia

During ischemia, the heart’s metabolic profile undergoes significant changes. The shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism results in a decrease in ATP production, leading to an accumulation of lactate and other metabolic byproducts. This shift is critical because it impairs the cell’s ability to maintain homeostasis.

We observe that the cellular response to ischemia involves several key metabolic changes, including:

- Reduced ATP production due to impaired oxidative phosphorylation

- Increased anaerobic glycolysis leading to lactate accumulation

- Disruption of ion homeostasis, particularly potassium and calcium

Transition from Reversible to Irreversible Injury

The transition from reversible to irreversible injury is a critical step in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. Initially, ischemic injury can be reversible if blood flow is restored promptly. However, prolonged ischemia leads to irreversible injury, characterized by cellular necrosis.

Research has shown that the duration and severity of ischemia are key determinants of the transition from reversible to irreversible injury. The table below summarizes the key differences between reversible and irreversible ischemic injury:

| Characteristics | Reversible Injury | Irreversible Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Changes | Swelling, mild mitochondrial damage | Severe mitochondrial damage, membrane disruption |

| Metabolic State | Impaired ATP production, lactate accumulation | Severe ATP depletion, ionic imbalance |

| Outcome | Recovery with reperfusion | Necrosis, cell death |

Understanding the cellular response to ischemia and the metabolic changes that occur during myocardial infarction is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. By targeting the mechanisms underlying the transition from reversible to irreversible injury, we can potentially reduce the extent of myocardial damage.

Step 5: Myocardial Necrosis and Cell Death Mechanisms

Myocardial necrosis, a result of severe ischemia, is a pivotal aspect of myocardial infarction pathology. When the heart muscle is deprived of oxygen and nutrients for an extended period, it leads to cell death and tissue damage. We will explore the mechanisms behind this critical step in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction.

Types of Cell Death in Pathology of Acute Myocardial Infarction

In the context of acute myocardial infarction, various types of cell death occur, including apoptosis and necrosis. Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that can be triggered by ischemia, while necrosis is a result of more severe ischemic injury. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing effective treatments.

Studies have shown that both apoptosis and necrosis contribute to the overall damage caused by myocardial infarction. The extent of cell death can vary depending on factors such as the duration of ischemia and the presence of underlying heart disease.

Histological Markers of Myocardial Necrosis

Histological examination of the heart tissue after myocardial infarction reveals specific markers of necrosis. These include the presence of dead cells, inflammation, and scarring. The histological changes can provide valuable information about the extent and timing of the infarction.

Some of the key histological markers of myocardial necrosis include:

- Nuclear changes, such as pyknosis and karyolysis

- Loss of cellular striations

- Infiltration of inflammatory cells

- Presence of granulation tissue and fibrosis

These changes are essential for diagnosing myocardial infarction and understanding its pathology. By examining the histological markers, we can gain insights into the underlying mechanisms of myocardial necrosis and its impact on the heart.

Step 6: Inflammatory Response and Debris Clearance

After a myocardial infarction, the inflammatory response plays a crucial role in clearing debris. This complex process is essential for initiating the healing process and preparing the affected area for scar formation.

Acute Inflammatory Phase

The acute inflammatory phase is characterized by the immediate response to myocardial injury. Within hours of MI, neutrophils are recruited to the site of injury, where they play a key role in clearing dead cells and debris.

This initial response is crucial for preventing infection and setting the stage for the subsequent healing phases. The neutrophils’ activity is tightly regulated to prevent excessive damage to the surrounding tissue.

Role of Neutrophils and Macrophages

Neutrophils are the first line of defense, arriving early in the inflammatory process. They are followed by macrophages, which are essential for the resolution of inflammation and the promotion of tissue repair.

Macrophages engulf apoptotic neutrophils and debris, facilitating the transition from the inflammatory phase to the reparative phase. This process is vital for the clearance of dead cells and the initiation of healing.

Cytokine Signaling in Post-MI Inflammation

Cytokine signaling plays a pivotal role in regulating the inflammatory response after MI. Various cytokines are released, including pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, which orchestrate the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells.

The balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals is crucial for optimal healing. An imbalance can lead to either inadequate healing or excessive inflammation, both of which can have adverse outcomes.

In conclusion, the inflammatory response and debris clearance are critical steps in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. Understanding these processes can provide valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets for improving outcomes after MI.

Step 7: Scar Formation and Cardiac Remodeling

The final step in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction involves scar formation and cardiac remodeling, crucial for understanding long-term outcomes. After a myocardial infarction, the heart undergoes a healing process that ultimately leads to the formation of a scar. This process is complex and involves various cellular and molecular mechanisms.

Fibroblast Activation and Collagen Deposition

Fibroblast activation is a key event in the scar formation process. Upon activation, fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts, which are responsible for producing extracellular matrix proteins, including collagen. The deposition of collagen is essential for forming a strong scar that can withstand the mechanical stresses of the heart.

Collagen deposition is a tightly regulated process, involving the coordinated action of various growth factors and cytokines. The resulting scar tissue is composed primarily of type I and III collagen, which provides the necessary strength and structure to the infarcted area.

Ventricular Remodeling Processes

Ventricular remodeling refers to the changes in the size, shape, and function of the heart after MI. This process can involve both the infarcted and non-infarcted regions of the ventricle. Ventricular remodeling is influenced by the extent of scarring, as well as by hemodynamic factors such as blood pressure and volume overload.

The remodeling process can lead to either adaptive or maladaptive changes. Adaptive remodeling helps to maintain cardiac function, while maladaptive remodeling can result in further deterioration of heart function, potentially leading to heart failure.

| Remodeling Process | Description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Remodeling | Compensatory changes to maintain cardiac output | Preserved cardiac function |

| Maladaptive Remodeling | Progressive changes leading to ventricular dilatation | Deterioration of heart function |

Long-term Consequences of Scarring

The long-term consequences of scarring after MI are significant. The scar tissue formed during the healing process is not contractile and can lead to reduced cardiac function. The extent of scarring and the resulting ventricular remodeling determine the patient’s long-term prognosis.

Understanding the mechanisms of scar formation and cardiac remodeling is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at improving outcomes in patients with MI. By targeting the processes involved in scar formation and ventricular remodeling, it may be possible to mitigate the adverse effects of MI and improve cardiac function.

Conclusion: Clinical Implications of MI Pathophysiology

Understanding the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction (MI) is crucial for developing effective clinical strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Research has shown that knowledge of MI pathophysiology informs clinical practice, guiding the development of new therapeutic approaches.

We have explored the complex processes involved in MI, from endothelial dysfunction to scar formation. The clinical implications of this understanding are significant, enabling healthcare providers to tailor treatments to individual patient needs and improve outcomes.

By grasping the intricacies of MI pathophysiology, we can better appreciate the importance of timely intervention and the role of various therapeutic strategies in managing cardiac infarction. This knowledge ultimately enhances patient care and supports the development of innovative treatments.

As we continue to advance our understanding of MI pathophysiology, we can expect to see improvements in clinical practice, leading to better patient outcomes and enhanced quality of life for those affected by cardiovascular disease.

What is myocardial infarction?

Myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow to the heart is severely blocked, causing damage to the heart muscle due to lack of oxygen.

What are the main types of myocardial infarction?

The main types are ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) and Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI), differentiated by electrocardiogram (ECG) findings and the level of cardiac biomarkers.

What is the role of atherosclerosis in myocardial infarction?

Atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in the arteries, is a key underlying process in the development of myocardial infarction, as it can lead to plaque rupture and subsequent thrombosis.

How does inflammation contribute to the pathophysiology of MI?

Inflammation plays a crucial role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis, contributing to plaque instability and increasing the risk of plaque rupture.

What are the modifiable risk factors for myocardial infarction?

Modifiable risk factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and physical inactivity, which can be addressed through lifestyle changes and medical treatment.

What is the significance of endothelial dysfunction in MI pathophysiology?

Endothelial dysfunction is an early step in the development of atherosclerosis, leading to impaired vasodilation, increased adhesion molecule expression, and enhanced permeability, facilitating the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

How does plaque rupture lead to myocardial infarction?

Plaque rupture exposes highly thrombogenic lipid-rich material to the bloodstream, triggering the activation of the thrombotic cascade, which can result in occlusive thrombosis and subsequent myocardial infarction.

What is the difference between complete and partial coronary occlusion in MI?

Complete occlusion results in STEMI, with more extensive myocardial damage, while partial occlusion may lead to NSTEMI or unstable angina, depending on the degree of ischemia.

What is the ischemic cascade in the context of myocardial infarction?

The ischemic cascade refers to a series of events initiated by ischemia, including metabolic changes, electrical dysfunction, and eventually, cell death, which progresses in a wavefront pattern from the subendocardium to the subepicardium.

How does the inflammatory response contribute to post-MI healing?

The inflammatory response is crucial for clearing necrotic debris and initiating the healing process, involving the coordinated action of neutrophils, macrophages, and various cytokines.

What are the long-term consequences of scar formation after MI?

Scar formation leads to ventricular remodeling, which can result in changes to the heart’s structure and function, potentially leading to heart failure, arrhythmias, and other complications.

How does understanding the pathophysiology of MI improve patient outcomes?

Understanding the pathophysiology of MI informs clinical practice, enabling healthcare providers to develop targeted therapeutic strategies, improve risk stratification, and enhance patient care.

References:

• Mechanic, O. J., Gavin, M., Grossman, S., & Ziegler, K. (2023). Acute myocardial infarction. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459269/

• Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. (n.d.). Consensus. https://consensus.app/questions/pathophysiology-of-myocardial-infarction/

• Myocardial infarction. (n.d.). StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537076/