Last Updated on November 27, 2025 by Bilal Hasdemir

When you read a medical report that mentions “thoracic aortic ectasia,” it’s natural to feel uneasy. The aorta is the body’s largest artery and the main pathway for blood leaving the heart. Any mention of widening or enlargement can sound alarming. However, thoracic aortic ectasia does not always mean there is an immediate danger. Understanding what this term means and how it differs from an aneurysm can help patients take the right steps for their heart and vascular health.

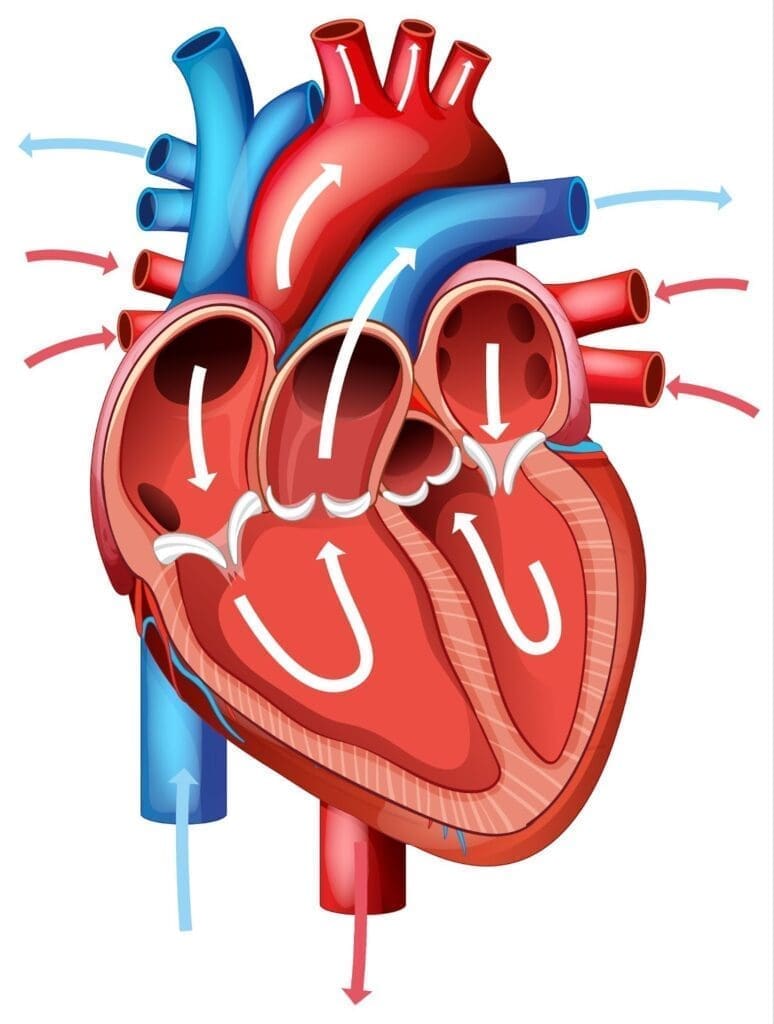

Understanding the Thoracic Aorta

The thoracic aorta is the section of the aorta that runs through the chest, starting from where it leaves the heart. It has several important parts: the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the descending thoracic aorta. It delivers oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body, making it essential for every organ’s proper function.

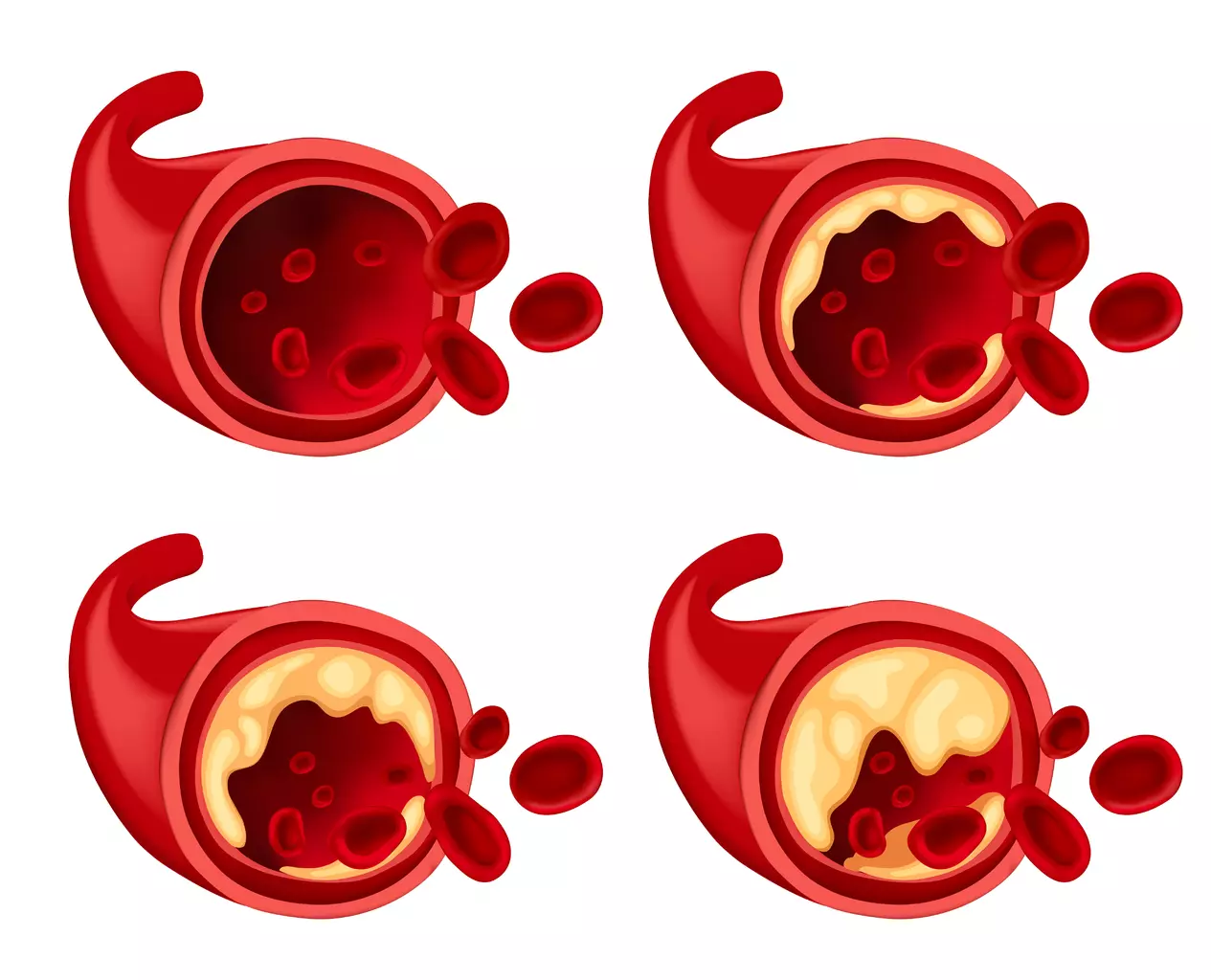

The wall of the aorta is made up of three layers that must remain strong and flexible. Over time, certain conditions can cause these layers to weaken, leading to changes in shape or size. When the aorta starts to widen but does not yet reach the size of an aneurysm, it is called ectasia.

What Is Thoracic Aortic Ectasia?

Thoracic aortic ectasia refers to a mild, uniform widening of the thoracic aorta that is less than 50 percent greater than its normal diameter. In simpler terms, it means that the aorta is slightly larger than usual but not large enough to be called an aneurysm.

A typical adult’s ascending aorta measures up to about 3.7 centimeters in diameter. Ectasia is usually diagnosed when the measurement falls between 3.7 and 4.0 centimeters, depending on body size and age. Because it does not meet the definition of an aneurysm, ectasia is considered an early or mild form of dilation. It often appears on imaging scans that were done for unrelated reasons, such as chest CTs or MRIs.

When a report says that the “aorta is mildly ectatic,” it means that this gentle widening has been observed. Most of the time, the patient has no symptoms, and the finding is simply noted for future monitoring.

Ectasia vs. Aneurysm: What’s the Difference?

The main difference between aortic ectasia and an aortic aneurysm lies in the degree of enlargement. An aneurysm is defined as an increase in the aorta’s diameter by 50 percent or more compared to what is considered normal for that section. For the ascending aorta, an aneurysm is typically diagnosed when the diameter exceeds 4.5 to 5.0 centimeters.

Ectasia, on the other hand, refers to smaller, more gradual widening that does not reach aneurysmal proportions. While both conditions involve a weakened arterial wall, ectasia poses a lower immediate risk of rupture or dissection. However, both require monitoring since ectasia can progress into an aneurysm over time.

Causes and Risk Factors

Several factors can contribute to thoracic aortic ectasia. The most common causes include:

- Aging: As people age, the aortic wall naturally loses some of its elasticity. This can lead to mild enlargement over time.

- High blood pressure (hypertension): Constantly elevated blood pressure increases stress on the aortic wall, promoting dilation.

- Atherosclerosis: Plaque buildup inside the arteries weakens the wall and makes it more likely to expand.

- Connective tissue disorders: Conditions such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome affect the structural proteins in the arterial wall, leading to weakness and widening.

- Bicuspid aortic valve: People with this congenital heart condition often develop changes in the ascending aorta, including ectasia or aneurysm.

- Inflammation and infection: Rarely, inflammatory conditions or infections of the aorta (aortitis) can cause ectatic changes.

- Trauma: Injury to the chest or aorta may result in wall damage that later contributes to dilation.

Symptoms and Detection

Most people with thoracic aortic ectasia do not experience symptoms. The condition is usually discovered incidentally through imaging such as echocardiography, CT, or MRI scans performed for other reasons. In some cases, patients may notice vague symptoms like mild chest discomfort, but these are not specific to ectasia.

Routine screening is not recommended for everyone. However, patients with known risk factors—such as connective tissue disease, bicuspid aortic valve, or family history of aortic aneurysm—should undergo periodic imaging to check the size and stability of the aorta.

How Serious Is Thoracic Aortic Ectasia?

The seriousness of thoracic aortic ectasia depends largely on its size, rate of growth, and underlying causes. Mild ectasia, especially when stable, often does not pose an immediate danger. However, because the aorta is a high-pressure vessel, even small weaknesses can worsen over time.

Doctors typically become more concerned if the aortic diameter increases by more than 0.5 centimeters per year or approaches aneurysmal thresholds. This is why regular monitoring is crucial. If detected early, lifestyle and medical interventions can help slow or prevent progression.

Diagnosis and Imaging

Accurate diagnosis requires high-quality imaging. The most common methods include:

- Echocardiography (Echo): Often used as a first-line tool, especially to measure the ascending aorta near the heart.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides detailed cross-sectional images, helping visualize the entire thoracic aorta.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Offers precise measurement without radiation exposure, making it ideal for long-term follow-up.

Radiologists measure the diameter of the aorta at specific points. These measurements are then compared to standardized values based on age, sex, and body size.

Treatment and Monitoring

For patients with mild thoracic aortic ectasia, the primary approach is medical management and surveillance rather than surgery. The main goals are to reduce strain on the aortic wall and prevent further enlargement. Treatment usually includes:

- Blood pressure control: Keeping blood pressure within a healthy range (ideally under 120–130 mm Hg) is vital. Medications such as beta-blockers or ACE inhibitors are often prescribed.

- Lifestyle changes: A heart-healthy lifestyle plays a major role in preventing progression. This includes regular exercise (as approved by a doctor), a diet low in saturated fats and sodium, quitting smoking, and managing stress.

- Regular imaging follow-up: Depending on the size and stability of the ectasia, imaging may be recommended every 6 to 12 months.

- Treatment of underlying causes: If ectasia is related to a genetic condition or inflammatory disease, addressing the root cause is essential.

Surgery is not typically recommended unless the aorta reaches aneurysm size or the patient has high-risk factors, such as rapid enlargement or strong family history of dissection.

Prevention and Long-Term Outlook

Preventing thoracic aortic ectasia centers on maintaining vascular health. Managing blood pressure, avoiding tobacco, eating a balanced diet, and keeping cholesterol under control all help preserve the aorta’s strength. For those with inherited conditions, regular medical checkups and early interventions can make a significant difference.

The long-term outlook for patients with mild ectasia is generally positive when the condition is detected early and managed properly. Many people live full, active lives without ever needing surgery.

Liv Hospital’s Approach to Thoracic Aortic Care

At Liv Hospital, cardiovascular specialists apply the latest scientific evidence and clinical guidelines to manage conditions like thoracic aortic ectasia. Their patient-centered approach ensures that each individual receives personalized care, from accurate diagnosis to long-term follow-up.

The hospital’s cardiovascular surgery department emphasizes collaboration between cardiologists, radiologists, and surgeons to deliver comprehensive care. This multidisciplinary model allows for early detection, precise monitoring, and preventive strategies that protect patients from complications. Liv Hospital’s mission—to set international standards in patient safety, ethics, and innovation—is reflected in its commitment to continuous quality improvement and advanced care in thoracic and cardiovascular medicine.

Conclusion

Thoracic aortic ectasia represents an early stage of aortic enlargement that requires attention but not alarm. It differs from an aneurysm mainly in degree, not in kind. With careful monitoring, medical management, and lifestyle modifications, most patients can keep their aortic health stable and avoid serious complications. Understanding the condition empowers patients to take preventive steps, and with expert guidance from specialized teams such as those at Liv Hospital, long-term outcomes can remain excellent.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Baptist Health. (n.d.). Aortic aneurysm and enlarged aorta: Causes and symptoms. Retrieved from https://www.baptisthealth.com

National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2020). Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: Pathophysiology and management. PMC7413567. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7413567

NHS. (2023). Abdominal and thoracic aortic aneurysm overview. Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm