Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a blood disorder that affects children, causing a low platelet count. It’s a condition that can be concerning for parents, but the good news is that many children recover from it. Do kids recover from ITP? Yes! Learn about low platelets thrombocytopenia in children and the amazing spontaneous recovery rate. Powerful and positive facts.

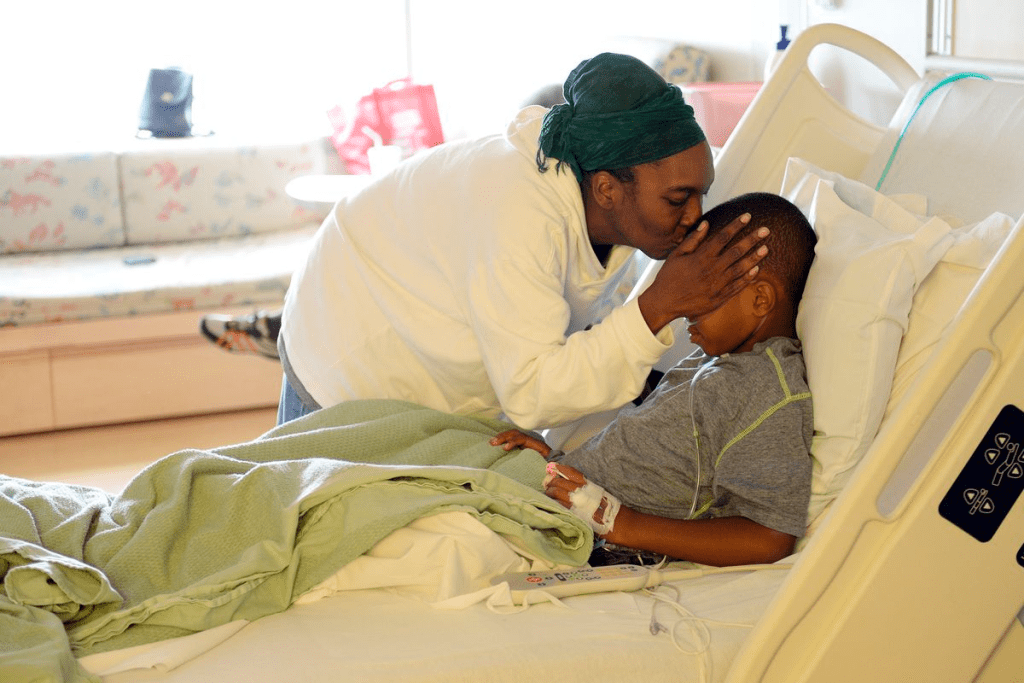

Seeing your child diagnosed with ITP can be distressing. But, studies show that about 80% of children with ITP recover within 6-12 months. This condition is often a self-limiting disorder, meaning it typically resolves on its own with proper care and monitoring.

As we explore the facts and outcomes of ITP in children, it’s essential to understand the latest research guiding ITP care. This knowledge helps us provide the best possible support for children affected by this condition.

Key Takeaways

- ITP is a common blood disorder in children characterized by a low platelet count.

- About 80% of children with ITP recover within 6-12 months.

- ITP is often a self-limiting condition that resolves on its own.

- Proper care and monitoring are key for children with ITP.

- The latest research guides ITP care, improving outcomes for children.

What Is Childhood ITP? Understanding the Condition

ITP, or Immune Thrombocytopenia, is when the immune system attacks platelets in kids. This leads to low platelet counts, causing bruising and bleeding. Knowing about ITP helps parents and doctors manage it well.

Definition and Pathophysiology

Childhood ITP happens when the immune system destroys platelets, often due to a virus. The body sees platelets as enemies and attacks them. This lowers platelet counts, raising the chance of bleeding.

“The pathophysiology of ITP involves a complex interplay between the immune system and platelet production,” as noted in recent studies. The exact mechanisms are not fully understood, but it is clear that both antibody-mediated and cell-mediated immunity play roles.

Acute vs. Chronic Classification

ITP in children can be acute or chronic. Acute ITP is common and usually goes away in six months. Chronic ITP lasts longer, needing ongoing care.

- Acute ITP: Typically resolves on its own within a few weeks to six months.

- Chronic ITP: Persists beyond six months, requiring long-term monitoring and treatment.

Prevalence in Pediatric Populations

ITP is common in kids worldwide. Studies show it affects about 4-5 per 100,000 children each year. Knowing this helps in spreading awareness and improving diagnosis.

Understanding ITP is essential for managing it. Early recognition by parents and doctors leads to better care for kids with ITP.

Recognizing the Signs of Low Platelet Thrombocytopenia in Children

ITP, or Immune Thrombocytopenia, in children shows up in certain ways. Parents and caregivers need to know these signs. Spotting them early helps get the right treatment fast.

Common Symptoms and ITP Bruising Patterns

Children with ITP might get bruising. This shows up as purple or red spots on the skin. These spots happen because the blood can’t clot well due to low platelets.

Petechiae, or small spots, can also appear. They often show up on the legs, arms, and chest. Nosebleeds (epistaxis) can happen too because of the low platelet count.

Differences Between Childhood and Adult Presentation

ITP symptoms can look similar in all ages, but kids show them differently. Kids often get symptoms quickly, while adults might notice them slowly.

Also, kids with ITP usually don’t have other health problems like adults do. This can change how the condition is treated.

When to Seek Medical Attention

If your child bruises a lot, has nosebleeds, or spots, see a doctor. A pediatrician can check the platelet count and decide what to do next.

If your child’s platelet count is very low, get them checked right away. This is important to avoid serious problems.

Getting a diagnosis and treatment early can really help kids with ITP. Knowing the signs helps parents take a big role in their child’s health.

Diagnosis and Initial Evaluation

When a child might have ITP, a detailed check is key to confirming it. This includes both a doctor’s assessment and lab tests. These steps help find out why the platelets are low.

Laboratory Tests and Platelet Count Thresholds

The first step is a complete blood count (CBC) to check the platelet count. A count under 100,000/μL is seen as thrombocytopenia. Counts under 20,000/μL are very low. The CBC also checks for other blood issues.

More tests might include blood smears to look at platelet and blood cell shapes. These are important to spot other possible problems.

Ruling Out Other Causes of Extremely Low Platelets

To diagnose ITP, other reasons for extremely low platelets must be ruled out. This includes leukemia, aplastic anemia, and bone marrow issues. A detailed medical history and physical check are vital.

Tests like viral serologies and autoimmune markers might be done. They help find other conditions that could causelow platelet thrombocytopenia.

Bone Marrow Examination: When Is It Necessary?

A bone marrow test is not always needed for ITP. But it might be considered in some cases. This includes unusual symptoms, not responding to treatment, or suspecting bone marrow failure or leukemia, nd low platelet count.

Deciding on a bone marrow biopsy depends on each case. It’s about weighing the benefits against the risks and discomfort to the child.

Recovery Statistics for Pediatric ITP

Pediatric ITP recovery rates are key to managing the condition well. Knowing these stats helps doctors and parents make better treatment choices.

Spontaneous Remission Rates Within the First Year

About 80% of kids with ITP get better on their own within 6 to 12 months. This means most kids don’t need ongoing treatment. The chance of getting better on their own is a big factor in how ITP is first treated in kids.

Age-Related Recovery Patterns

Age affects how kids with ITP get better. Younger kids are more likely to get better without treatment than older kids. This age difference is important when figuring out a child’s ITP prognosis.

For example, kids under 10 often get better faster than teens. This shows why age matters when planning treatment for ITP.

Predictors of Acute vs. Chronic Course

Knowing if a child’s ITP will be short-term or long-term is key. Several things can tell us this, like the first platelet count and how well the child responds to treatment.

Kids who quickly respond to treatment and have a high platelet count usually have a short-term ITP. But kids who don’t respond well or have other health issues might have a long-term ITP. Knowing this helps doctors tailor treatment to each child’s needs.

Factors Influencing Recovery from Childhood ITP

Recovery from Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) in children depends on several key factors. Knowing these elements is key to predicting outcomes and managing the condition well.

Impact of Age at Diagnosis

The age at diagnosis with ITP greatly affects recovery chances. Younger children tend to have higher recovery rates, with those under 10 showing the best results. Research shows that kids in this age group are more likely to get better on their own.

For example, kids under 5 are more likely to recover from ITP within a year after diagnosis. This shows how important age is when looking at a child’s prognosis.

Role of Preceding Viral Infections or Vaccinations

Having had a viral infection or vaccination recently can affect ITP in children. Children who get ITP after a viral infection often have a better chance of getting better. This is because their condition might resolve on its own.

Viral infections can cause ITP, but they can also lead to spontaneous recovery. Vaccinations can also trigger ITP, but the risk is low, and the condition usually doesn’t last long.

Initial Platelet Count and Disease Severity

The platelet count at diagnosis and the severity of symptoms are key in determining outcomes for children with ITP. Children with very low platelet counts are at a higher risk of bleeding complications, which can affect their recovery.

But the severity of ITP at diagnosis doesn’t always mean the long-term outcome. Some children with severe thrombocytopenia might recover on their own, while others with milder symptoms might develop chronic ITP.

Genetic and Immunological Considerations

Genetic and immunological factors also play a role in recovery from ITP in children. Research shows that certain genetic predispositions and immune system dysfunctions can influence recovery chances and the risk of chronic ITP.

Understanding these genetic and immunological factors helps doctors tailor treatments to each patient. This can improve outcomes for children with ITP.

Treatment Approaches and Their Effect on Recovery

Managing ITP in kids needs a deep understanding of when to watch and when to act. The choice depends on several things. These include how bad the symptoms are, the risk of bleeding, and the side effects of treatment.

Observation vs. Intervention Strategies

For kids with mild ITP and no big bleeding, watching closely might be the best plan. This lets doctors keep an eye on the child without starting treatment right away. But if the symptoms are worse or there’s a lot of bleeding, doctors need to act fast. They do this to quickly raise platelet counts and lower the risk of serious bleeding.

First-Line Therapies: IVIG, Anti-D, Corticosteroids

First treatments for ITP are intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), anti-D immunoglobulin, and corticosteroids. These aim to quickly boost platelet counts by stopping the immune system from destroying them. IVIG is often first because it works fast. Corticosteroids are also common because they’re good at raising platelet counts. Anti-D is for Rh-positive patients who haven’t had their spleen removed.

- IVIG: Blocks Fc receptors in the spleen, reducing platelet destruction.

- Corticosteroids: Lower antibody production against platelets and slow down platelet clearance.

- Anti-D: Targets RhD antigen on red blood cells, reducing platelet destruction.

Second-Line Options for Persistent ITP

For kids who don’t get better with first treatments or have ongoing ITP, second-line options are considered. These include rituximab, a B-cell-targeting antibody, and thrombopoietin receptor agonists like eltrombopag or romiplostim. These stimulate platelet production. The right second-line treatment depends on how bad the disease is, the child’s health, and the treatment’s side effects.

Novel Treatments and Clinical Trials

New treatments for ITP are being studied in clinical trials. These include new thrombopoietin receptor agonists, Syk inhibitors, and other targeted therapies. These aim to offer better and safer treatments for kids with ITP. Joining clinical trials might give kids with hard-to-treat ITP access to new treatments that could help them get better.

Understanding the different treatments and their effects helps doctors tailor care for kids with ITP. This makes care better and improves outcomes.

Managing Chronic ITP in Children

Managing chronic ITP in kids is a long-term effort. It needs careful planning and teamwork among doctors, patients, and families. A good care plan covers medical needs, lifestyle changes, and emotional support.

Long-term Monitoring Protocols

Keeping an eye on chronic ITP is key. This means:

- Regular blood tests to check platelet counts

- Changing treatment plans as needed based on counts and symptoms

- Watching for signs of bleeding or other problems

Doctors and families work together to set up a monitoring plan. They aim to be careful without disrupting the child’s life too much.

Activity Restrictions and Lifestyle Considerations

Kids with chronic ITP might need to make some lifestyle changes. This could be:

- Staying away from contact sports or high-risk activities

- Being careful to avoid falls or bumps

- Knowing the signs of bleeding and when to get help

While these changes are important, it’s also key to let kids enjoy activities that make them happy. This helps them feel normal.

Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Care

As kids with chronic ITP grow up, they need to switch to adult care. This involves:

- Getting to know adult healthcare providers

- Learning about their condition, treatment, and how to manage it

- Ensuring their medical records and care plans are transferred smoothly

A smooth transition helps keep care consistent. It also helps young adults take charge of their health.

Psychological Support for Children with Chronic ITP

Chronic ITP can affect kids emotionally and psychologically. It’s important to offer psychological support. This can include:

- Counselling or therapy to help with anxiety, fear, or other feelings

- Support groups for kids and families to share and get advice

- Learning about the condition to reduce fear and uncertainty

By focusing on the emotional side of chronic ITP, healthcare providers can help kids and their families deal better with the condition.

Potential Complications and Their Frequency

Parents and doctors need to know about ITP complications in kids. ITP is usually not serious, but low platelet counts can be a problem. We need to manage these risks well.

Risk Assessment for Bleeding Events

Bleeding is a big worry for kids with ITP. The chance of bleeding goes up when platelet counts go down. Even with counts below 20,000/μL, serious bleeding can happen. Kids might see spots on their skin, have nosebleeds, or have other bleeding issues.

But, more serious bleeding, like in the belly or bladder, is rare. It’s very important to get help right away if this happens.

Intracranial Hemorrhage: Incidence and Prevention

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is a scary but rare complication of ITP. It happens in less than 1% of kids with ITP. Children with very low platelet counts and a history of bleeding are at higher risk.

To prevent ICH, we avoid head injuries and keep platelet counts safe. Quick treatment of ICH is key to avoiding lasting brain damage.

Impact on Quality of Life and Development

ITP can really affect a child’s life and growth. They might have to go to the doctor a lot and could even need to stay in the hospital. It’s also important to help kids deal with the stress and feeling left out that comes with chronic illness.

Also, ITP can slow down a child’s development. This is because they might not be able to do things that other kids do.

Distinguishing ITP from Leukemia and Low Platelet Count

Telling ITP apart from leukemia or other low platelet issues is key. Leukemia can also cause low platelets. A bone marrow test might be needed to check for leukemia or other problems.

Getting the right diagnosis is very important. It helps us know how to treat and manage the condition properly.

Conclusion: The Positive Outlook for Children with ITP

Children with Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) often have a good prognosis. Most see their platelet counts go back to normal within a year. This shows a bright future for those recovering from ITP.

For kids with chronic ITP, the right care lets them stay active. Knowing the condition and its signs is key. We focus on giving top-notch care and support, aiming to help every child with ITP.

Thanks to new treatments, kids with ITP can live better lives. We’re dedicated to caring for them with kindness and expertise. Our goal is to help them recover fully and thrive.

FAQ’s:

What is ITP in children?

ITP, or Immune Thrombocytopenia, is a condition where the immune system attacks platelets. This leads to low platelet counts. Children with ITP often bruise easily and bleed more than usual.

How common is ITP in pediatric populations?

ITP is rare in kids, affecting about 1 in 100,000 each year. It can happen at any age, but some ages are more common.

What are the symptoms of ITP in children?

Symptoms include bruising, small red spots on the skin, nosebleeds, and bleeding gums. Some kids might also feel tired or unwell.

How is ITP diagnosed in children?

Doctors use a few steps to diagnose ITP. They check the child’s health, do blood tests, and sometimes a bone marrow test. This helps find out if the platelet count is low for a good reason.

Can ITP be cured in children?

Many kids with ITP get better on their own, often within a year. How likely they are to recover depends on their age and how low their platelet count is.

What factors influence recovery from ITP in children?

Several things can affect how well a child recovers from ITP. These include their age, platelet count, any recent illnesses, and their immune system.

What are the treatment options for ITP in children?

Treatment varies based on how severe the ITP is. Mild cases might just need watching. For more serious cases, doctors might use IVIG or steroids. There are also other treatments for kids who don’t get better.

How is chronic ITP managed in children?

Managing chronic ITP means keeping an eye on the child’s health and making sure they stay safe. They might need to avoid certain activities and get support for their lifestyle. It’s also important to plan for when they’ll move to adult care.

What are the possible complications of ITP in children?

One big worry is bleeding, like in the brain. ITP can also affect a child’s quality of life and how they develop.

How does ITP differ from leukemia in terms of low platelet count?

Both can have low platelet counts, but they’re different. Leukemia is a cancer in the bone marrow. ITP is when the immune system attacks platelets. Tests can tell them apart.

What is the outlook for children diagnosed with ITP?

Most kids with ITP do well and get better on their own. But they need good care and support to have the best outcome.

References

- Jung, J. Y., et al. (2016). Clinical course and prognostic factors of childhood immune thrombocytopenia. Annals of Laboratory Medicine, 36(5), 487“493.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5014913/

- Neunert, C., Terrell, D. R., Arnold, D. M., Buchanan, G., Cines, D. B., Cooper, N., … & Vesely, S. K. (2020). American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Advances, 3(23), 3829-3866.https://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/3/23/3829/465037/American-Society-of-Hematology-2019-guidelines-for