The twelve cranial nerves are key parts of our brain’s structure. Ten of these nerves start right from the brainstem. At Liv Hospital, we use deep knowledge of anatomy to help our patients. We focus on treating problems with these important nerve paths.where are the cranial nerves locatedWhat is the Platelet Count of Cancer Patients? Dangerous

The brainstem links our brain to our spinal cord. It controls things like breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. Knowing where the cranial nerves are on the brainstem helps us diagnose and understand how our body works.

Key Takeaways

- The brainstem is key for controlling automatic functions.

- Ten of the twelve cranial nerves start from the brainstem.

- Understanding cranial nerves is vital for diagnosing neurological conditions.

- Liv Hospital provides detailed care for conditions affecting cranial nerves.

- Accurate diagnosis is key to effective treatment outcomes.

The Fundamental Role of Cranial Nerves in Neuroanatomy

Learning about cranial nerves is key to understanding neuroanatomy. These nerves control many body functions, like feeling sensations and moving muscles. They are very important in medicine because problems with them can cause many neurological issues.

Definition and Classification of the Twelve Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves come in twelve pairs, each with its own name and number. They start at the head and go down to the tail. The first two, the olfactory and optic nerves, come from the brain. The rest come from different parts of the brainstem.

The names of the twelve cranial nerves are: Olfactory (I), Optic (II), Oculomotor (III), Trochlear (IV), Trigeminal (V), Abducens (VI), Facial (VII), Vestibulocochlear (VIII), Glossopharyngeal (IX), Vagus (X), Accessory (XI), and Hypoglossal (XII). Each one has its own job and area it covers.

Functional Categories: Sensory, Motor, and Mixed Nerves

Cranial nerves are divided into three groups: sensory, motor, and mixed. Sensory nerves send information about what we feel. Nerves I, II, and VIII deal with smell, sight, and hearing/balance.

Motor nerves make muscles move. Nerves III, IV, VI, XI, and XII control eye and facial movements, and tongue actions.

Mixed nerves have both sensory and motor parts. Nerves V, VII, IX, and X are mixed. For example, the trigeminal nerve has parts for feeling and for moving muscles.

Knowing these categories helps doctors diagnose and treat neurological problems. By understanding each nerve’s role, doctors can find and fix problems more easily.

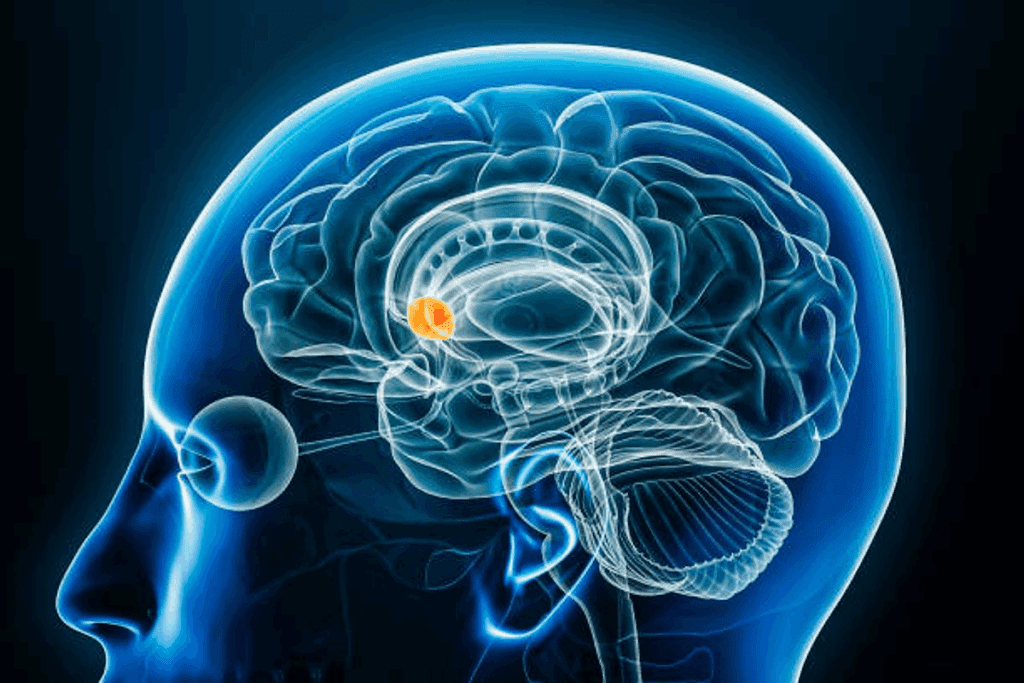

Where Are the Cranial Nerves Located? Brainstem Anatomy and Organization

The brainstem is a key part of our central nervous system. It’s where cranial nerves start. It connects the diencephalon to the spinal cord and cerebellum. This structure is vital for many neural functions, including controlling cranial nerves.

Brainstem Divisions: Midbrain, Pons, and Medulla Oblongata

The brainstem is split into three main parts: the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. Each part has its own features and houses specific cranial nerve nuclei. The midbrain is at the top and is linked to nerves III and IV.

The pons is below the midbrain and is home to nerves V, VI, VII, and VIII. The medulla oblongata is at the bottom and connects with nerves IX, X, XI, and XII.

Knowing these divisions is key for understanding the brainstem. Each part has unique structures and functions. This helps in the complex workings of neural pathways.

Topographical Organization of Cranial Nerve Nuclei

The cranial nerve nuclei in the brainstem are organized by function and location. This organization is essential for controlling our body’s functions, like eye movements and swallowing. The nuclei are set up in a specific pattern, with sensory ones on the sides and motor ones in the middle.

This setup makes for efficient signal transmission. Knowing where these nuclei are is important for diagnosing and treating neurological issues.

Cerebral Origins: Olfactory Nerve (CN I) and Its Pathways

The first cranial nerve, known as the olfactory nerve (CN I), carries smell information from the nose to the brain. It is a sensory nerve that helps us recognize different smells.

Anatomical Course from Nasal Epithelium to Olfactory Bulb

The olfactory nerve starts in the nasal cavity’s olfactory epithelium. This area has special neurons that catch smell molecules in the air. These neurons have cilia that reach into the mucus layer, where they meet smell molecules.

When smell molecules bind to the cilia, it sends a signal along the nerve fibers. These fibers go through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulb. There, the smell information is processed.

Functions and Clinical Testing of Smell Sensation

The main job of the olfactory nerve is to help us smell. Damage to it can cause anosmia, or a loss of smell. Doctors test smell by asking patients to identify different smells.

In a test, doctors use various smells to check a patient’s sense of smell. The patient must identify the smells with their eyes closed. The nostrils are tested separately to see if there’s any difference in smell perception.

Optic Nerve (CN II): The Second Cerebral Exception

The optic nerve is the second cranial nerve. It carries visual signals from the retina to the brain. This nerve is key to how we see and understand what we see.

Visual Pathway from Retina to Lateral Geniculate Nucleus

The journey of vision starts in the retina. Here, light turns into electrical signals. These signals then travel to the optic nerve.

The optic nerve leads to the optic chiasm. Here, fibers from each eye mix, combining their views. This is how we see the world around us.

After the optic chiasm, the signals become the optic tract. They end at the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) in the thalamus. The LGN processes this information before it reaches the brain.

Visual Field Defects and Clinical Assessment

Damage to the optic nerve can cause vision problems. For example, a problem before the optic chiasm can make one eye blind or very weak.

Problems after the optic chiasm can lead to more complex vision issues. These include losing half or a quarter of your vision, depending on where the damage is.

Location of Lesion | Visual Field Defect |

Optic Nerve | Unilateral blindness or severe impairment |

Optic Chiasm | Bitemporal hemianopia |

Optic Tract | Homonymous hemianopia |

Doctors check the optic nerve with a detailed eye exam. They test how well you see, check your field of vision, and look at the back of your eye. They might also use MRI to see if there’s any damage.

Midbrain Cranial Nerves: Origins and Functions

The oculomotor and trochlear nerves start in the midbrain. They help control eye movements and adjust to light changes. These nerves are key for moving our eyes and reacting to light.

Oculomotor Nerve (CN III): Controlling Eye Movements and Pupillary Response

The oculomotor nerve, or third cranial nerve, controls most eye movements. It also makes the pupil smaller and keeps the eyelid in place. It works with several muscles to help us track objects and see in 3D.

Functions of the Oculomotor Nerve:

- Controls most extraocular muscles

- Regulates pupillary constriction

- Maintains eyelid position

Trochlear Nerve (CN IV): The Only Posterior-Exiting Cranial Nerve

The trochlear nerve is the fourth cranial nerve. It’s special because it leaves the brainstem from the back. It helps the superior oblique muscle move the eye in a certain way.

Key Features of the Trochlear Nerve:

Feature | Description |

Innervation | Superior oblique muscle |

Function | Rotates eyeball downward and inward |

Unique Characteristic | Exits from the posterior aspect of the brainstem |

In conclusion, the oculomotor and trochlear nerves are vital for eye control and light adjustment. Knowing about them helps us understand and treat eye problems.

The Trigeminal Nerve (CN V) at the Pons: Sensory and Motor Divisions

The trigeminal nerve is a special nerve that comes out at the pons. It has two main parts: one for feeling and one for moving. This nerve helps us feel sensations from our face and move our jaw muscles. It splits into three main parts, each with its own job.

Ophthalmic, Maxillary, and Mandibular Branches

The trigeminal nerve has three main branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. The ophthalmic branch only feels sensations, covering the forehead, upper eyelid, and nose. The maxillary branch also feels sensations, covering the cheek, lower eyelid, and upper lip. The mandibular branch does both, feeling sensations on the lower lip, teeth, and ear, and moving the jaw muscles.

Trigeminal Neuralgia and Other Clinical Considerations

Trigeminal neuralgia is a painful condition that affects the trigeminal nerve. It causes sharp, stabbing pain in the face. Even simple actions like eating or talking can trigger it. Other issues like nerve trauma or infections can also cause problems.

Branch | Function | Areas Innervated |

Ophthalmic | Sensory | Forehead, upper eyelid, parts of the nose |

Maxillary | Sensory | Cheek, lower eyelid, upper lip |

Mandibular | Mixed (Sensory & Motor) | Lower lip, lower teeth, external ear (sensory); muscles of mastication (motor) |

Cranial Nerves at the Pontomedullary Junction

At the pontomedullary junction, we find the origins of three significant cranial nerves. These are the abducens nerve (CN VI), facial nerve (CN VII), and vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). They play key roles in eye movements, facial expressions, and hearing.

Abducens Nerve (CN VI): Lateral Rectus Innervation

The abducens nerve controls the lateral rectus muscle. This muscle is responsible for outward eye movement. Dysfunction of CN VI can lead to esotropia, where the eye turns inward.

Clinical testing of CN VI involves assessing eye movements, mainly abduction. A patient with abducens nerve palsy may experience double vision (diplopia) due to the inability to abduct the affected eye.

Facial Nerve (CN VII): Expression, Taste, and Autonomic Functions

The facial nerve controls facial expressions, transmits taste information from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and provides autonomic innervation to various glands.

Damage to CN VII can cause facial weakness or paralysis, loss of taste, and decreased salivation or tearing. The facial nerve is vulnerable to injury from conditions such as Bell’s palsy or trauma.

Function | Description |

Motor | Controls facial expressions, stapedius, and stylohyoid muscles |

Sensory | Taste sensation from anterior two-thirds of tongue |

Autonomic | Innervates salivary and lacrimal glands |

Vestibulocochlear Nerve (CN VIII): Balance and Hearing Mechanisms

The vestibulocochlear nerve transmits sensory information related to sound and balance. It has two divisions: the cochlear nerve for hearing and the vestibular nerve for balance.

Damage to CN VIII can cause hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo. Clinical assessment involves evaluating hearing thresholds and vestibular function through tests like the Romberg test or caloric reflex test.

In conclusion, the cranial nerves emerging at the pontomedullary junction are vital for various critical functions. Understanding their anatomy and clinical significance is essential for diagnosing and managing related neurological disorders.

Medulla Oblongata: Home to Four Critical Cranial Nerves

The medulla oblongata is the lowest part of the brainstem. It is where four important cranial nerves start. These nerves control different functions in our body.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX): Pharyngeal Sensation and Taste

The glossopharyngeal nerve sends signals from the pharynx and helps with swallowing. It also carries taste from the back third of the tongue. Damage to this nerve can cause swallowing problems and loss of taste.

- Provides sensory innervation to the pharynx

- Controls swallowing through motor innervation

- Transmits taste sensations from the posterior third of the tongue

Vagus Nerve (CN X): The Extensive Parasympathetic Network

The vagus nerve is very long and controls many functions. It affects heart rate, digestion, and breathing. It also helps keep the body balanced.

- Regulates heart rate through parasympathetic innervation

- Controls digestion through innervation of the gastrointestinal tract

- Influences respiration through innervation of the lungs

Accessory Nerve (CN XI): Sternocleidomastoid and Trapezius Control

The accessory nerve has two parts: a cranial root and a spinal root. The spinal root helps the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. This is important for moving the head and shoulders.

- Innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Controls the trapezius muscle

Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII): Tongue Movement and Speech

The hypoglossal nerve controls the tongue’s movements. This is key for speaking, swallowing, and eating. Damage to this nerve can make it hard to speak and swallow.

- Controls tongue movements

- Essential for speech articulation

- Important for swallowing and manipulating food

Complete Mapping of Cranial Nerves on the Brainstem

Mapping cranial nerves on the brainstem is key to understanding their roles and how they work together. The brainstem, made up of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, is where 10 of the 12 cranial nerves start or end. Knowing where these nerves are is important for diagnosing and treating brain and nerve problems.

Topographical Relationships Between Adjacent Nerves

The cranial nerves come out of the brainstem in a certain order. Their close positions to each other and other brainstem parts are important for spotting problems. For example, the trigeminal nerve (CN V) is near the cerebellum and brainstem’s hearing paths. This can cause complex symptoms if it gets compressed or damaged.

It’s important to know how each cranial nerve moves through the brainstem. The oculomotor (CN III) and trochlear (CN IV) nerves start in the midbrain. The abducens (CN VI), facial (CN VII), and vestibulocochlear (CN VIII) nerves are found at the pontomedullary junction.

Clinical Correlation: Brainstem Lesions and Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits

Lesions in the brainstem can cause problems with many cranial nerves because of their close arrangement. Damage to the brainstem can affect nearby nerves, leading to complex neurological issues. For instance, a lesion at the pontomedullary junction can harm the abducens (CN VI), facial (CN VII), and vestibulocochlear (CN VIII) nerves. This can cause eye muscle weakness, facial weakness, and hearing loss.

It’s critical to understand how brainstem lesions and cranial nerve problems are connected for accurate diagnosis and treatment. We use detailed neurological exams and imaging to find and treat lesions.

Practical Assessment and Examination of the Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerve examination is key in neurology. It checks each nerve’s function, both sensory and motor. Knowing how to assess these nerves is vital for diagnosing and treating neurological issues.

Systematic Approach to Cranial Nerve Examination

Examining cranial nerves systematically ensures a thorough check. We start with the olfactory nerve (CN I) by testing smell. The optic nerve (CN II) is checked with vision tests.

For the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducens (CN VI) nerves, we look at eye movements and pupil reactions. The trigeminal nerve (CN V) is tested for facial feeling and jaw strength.

The facial nerve (CN VII) is evaluated for facial expressions and taste. We also check the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) for hearing and balance.

Lower cranial nerves are tested next. The glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves are checked for swallowing and voice quality. The accessory nerve (CN XI) is tested for shoulder and head movements. Lastly, the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) is evaluated for tongue strength.

Documenting and Interpreting Cranial Nerve Findings

Recording cranial nerve findings accurately is essential. We note any nerve function issues. For example, a brainstem lesion might cause multiple nerve problems, which we document to plan treatment.

As

“The clinical examination of cranial nerves is a powerful tool in the diagnosis of neurological disorders.”

, it shows how critical a detailed assessment is.

By following a systematic method and documenting findings well, we offer top-notch care for neurological patients.

Learning the Cranial Nerves: Effective Strategies and Mnemonics

To understand cranial nerves, you need good learning strategies and memory tools. Knowing these nerves well is key to neuroanatomy and diagnosing brain issues.

Classical and Contemporary Memory Aids

Mnemonics help remember the 12 cranial nerves in order. A classic one is: “On Old Olympus’ Towering Top, A Finn And German Viewed Some Hops.” Each word starts with the first letter of a nerve: Olfactory, Optic, Oculomotor, Trochlear, Trigeminal, Abducens, Facial, Auditory (Vestibulocochlear), Glossopharyngeal, Vagus, Spinal Accessory, and Hypoglossal.

New memory aids are more fun and stick in your mind. Making up a sentence or joke can help a lot. For example:

- “Our Outstanding Owl Takes The Anatomy Guide Very Seriously Hopping”

- “Only Ourselves Take The Awkward Guests Visiting Santa’s House”

These tricks not only help remember the nerves but also their order.

Visual and Spatial Learning Techniques for Neuroanatomy

Visual and spatial learning are great for brain anatomy. Making mental or real maps of the brainstem and nerves helps a lot.

Some good visual methods include:

- Draw diagrams of the brainstem and mark the nerves.

- Use 3D models or digital tools to see nerve relationships.

- Color-code nerves by their function (sensory, motor, or mixed).

Using these visual methods with mnemonics helps learn cranial nerves better. This mix makes learning stick and is vital for medical work.

Conclusion: Integrating Cranial Nerve Knowledge into Clinical Practice

Knowing about cranial nerves is key for diagnosing and treating neurological issues. It’s important to understand their anatomy and function. This knowledge helps in diagnosing and treating many neurological conditions.

We’ve looked at the anatomy of the 12 cranial nerves and their roles. We’ve also seen how they relate to clinical practice. By using this knowledge, healthcare workers can give better care to those with neurological problems.

Using cranial nerve knowledge well helps healthcare providers work more efficiently. This leads to better care for patients with neurological issues.

FAQ

What is the brainstem and what is its role in controlling cranial nerves?

The brainstem connects the cerebrum to the spinal cord. It controls automatic functions like breathing and heart rate. It also houses the nuclei of the cranial nerves.

What are the 12 cranial nerves and their functions?

The 12 cranial nerves control various functions. They include sensory, motor, and mixed functions. Examples are smell, vision, and hearing.

Where are the cranial nerves located on the brainstem?

The cranial nerves are on the brainstem. It’s divided into three parts: midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. Each part has different nerves.

What is the significance of understanding the topographical organization of cranial nerve nuclei?

Knowing how cranial nerve nuclei are organized is key. It helps diagnose and treat neurological disorders. It lets us pinpoint nerve damage.

How do brainstem lesions affect cranial nerve function?

Brainstem lesions can harm multiple cranial nerves. This depends on the lesion’s location and size. Symptoms include vision problems and swallowing issues.

What is the role of the olfactory nerve (CN I) in smell sensation?

The olfactory nerve transmits smell information from the nose to the brain. Damage to it can cause anosmia, or loss of smell.

How is the optic nerve (CN II) assessed clinically?

The optic nerve is checked through visual field and acuity tests. These tests help find any defects or damage.

What are the functions of the trigeminal nerve (CN V)?

The trigeminal nerve has sensory and motor parts. It sends face sensation information and controls chewing.

What is the significance of the cranial nerves in clinical practice?

Understanding cranial nerve function is vital for diagnosing and treating neurological disorders. It’s essential for healthcare professionals.

How can one effectively learn and remember the cranial nerves?

Visual and spatial learning, along with memory aids, can help. They make learning the complex anatomy of cranial nerves easier.

References

World Health Organization. Evidence-Based Medical Guidance. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44477