Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The ovaries are two small, almond-shaped organs deep in the female pelvis, one on each side of the uterus. They are the main reproductive glands, making eggs and releasing important hormones like estrogen and progesterone. These hormones help control the menstrual cycle, keep bones strong, and affect heart health. The ovaries are held in place by ligaments and sit close to the fallopian tubes, uterus, bladder, and intestines. Because they are directly exposed to the fluid in the abdomen, cancer cells that break away from the ovary can easily spread throughout the abdominal cavity, reaching the lining and surfaces of other organs.

Doctors used to think ovarian cancer started only on the surface of the ovary. Now, research shows that many cases, especially the high-grade serous type, actually begin at the end of the fallopian tube. The fimbriae, which are finger-like ends of the tube, help catch the egg when it is released. Sometimes, early cancer cells called Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinomas (STIC) form in the fimbriae and then spread to the ovary, where they grow into tumors. Because of this, experts now talk about the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum as a single unit that can develop cancer in a similar way.

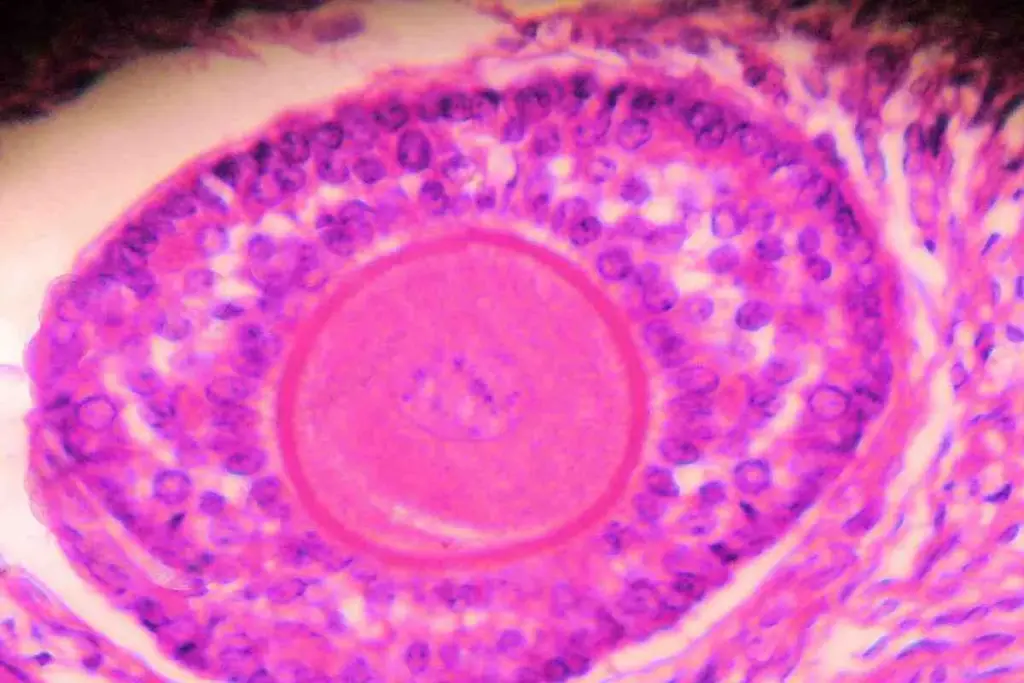

The ovary contains three main types of cells, and each can develop into cancer. The surface is covered by epithelial cells, the inside has germ cells that make eggs, and stromal cells provide structure and make hormones. Most ovarian cancers start in the epithelial cells, but knowing which cell type the cancer comes from helps doctors understand how the disease will behave and how best to treat it.

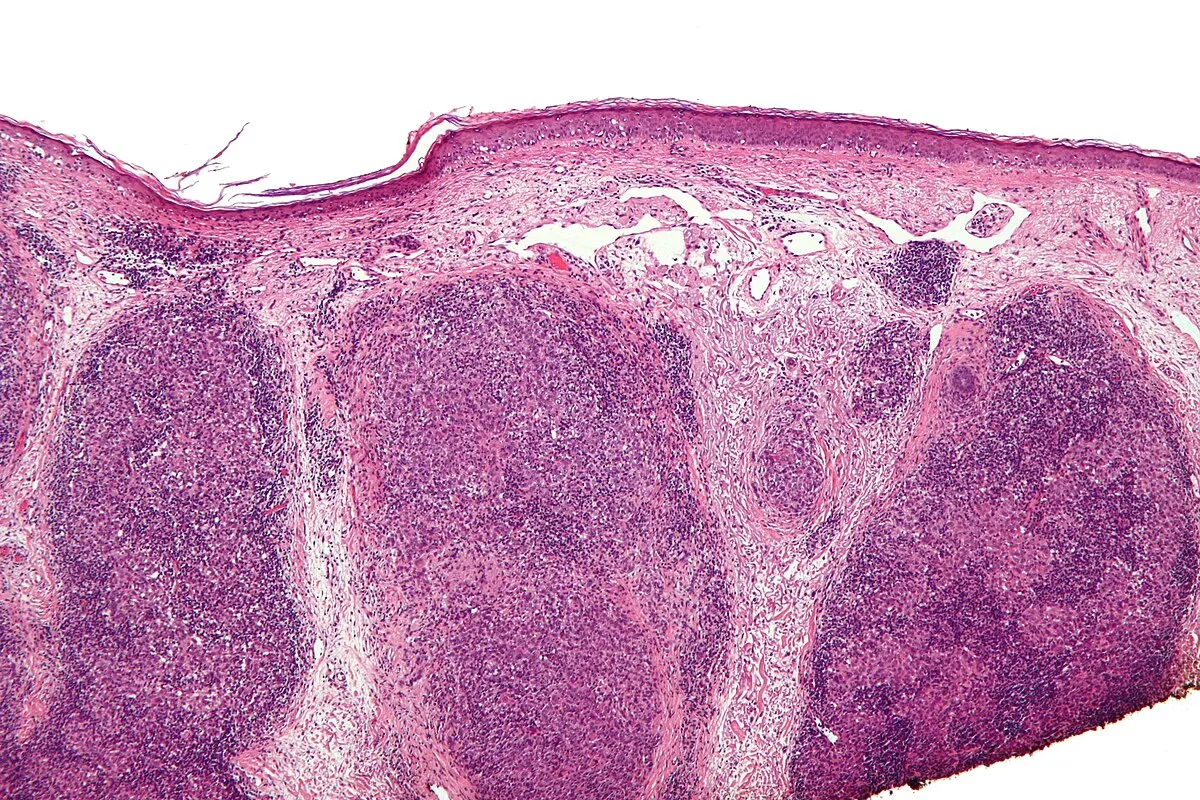

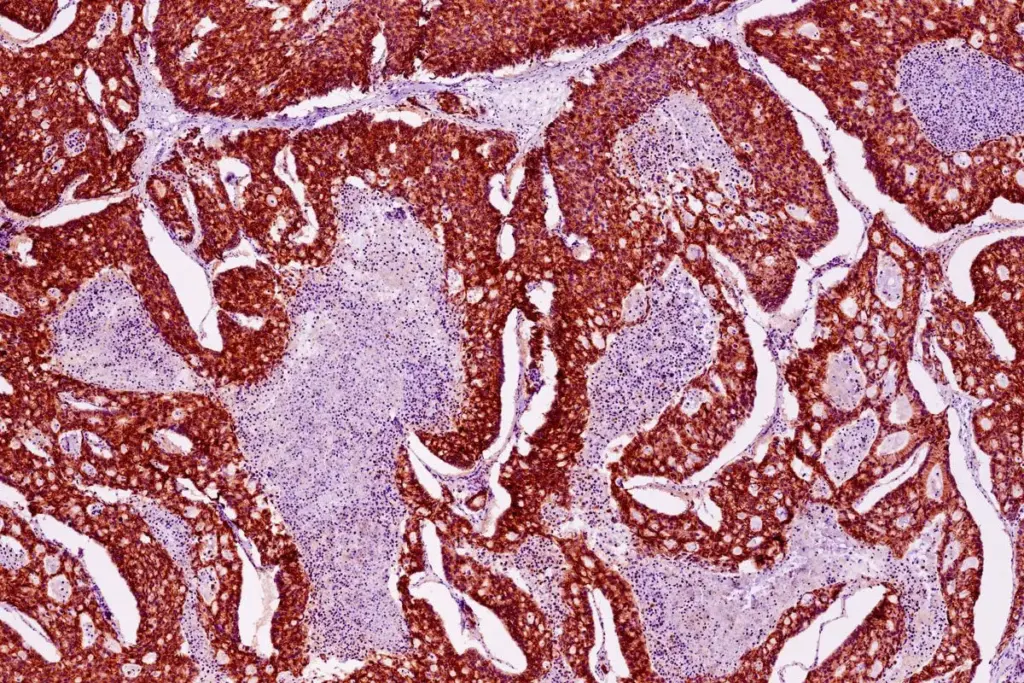

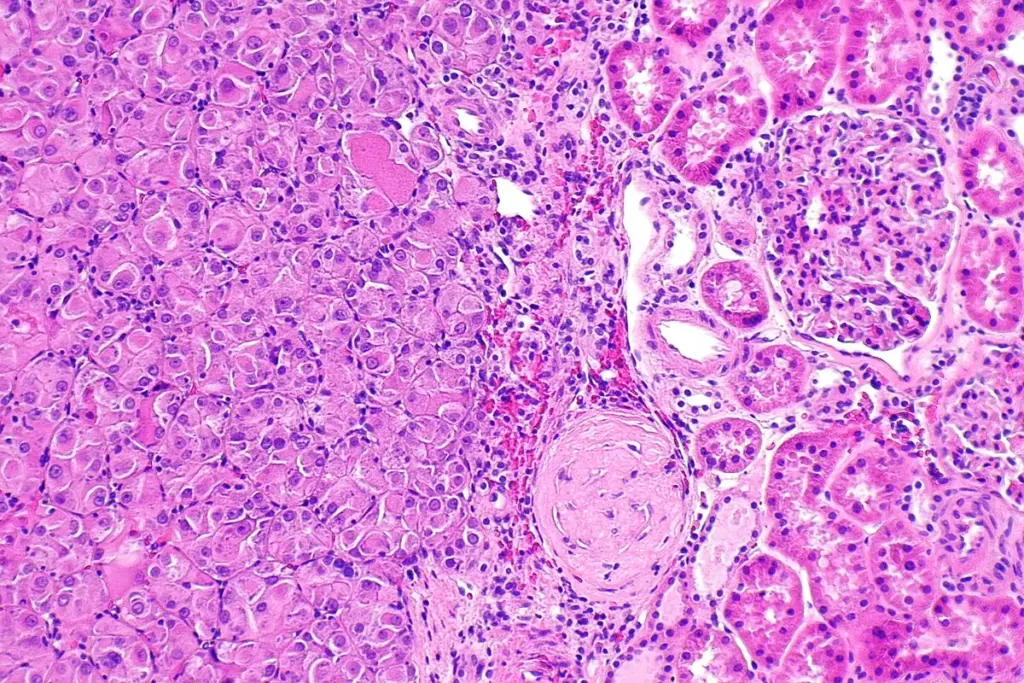

Epithelial ovarian cancer is not a singular disease but a collection of distinct histological subtypes, each with a unique genetic profile and clinical course. High-Grade Serous Carcinoma (HGSC) is the most common and aggressive form, accounting for the majority of advanced-stage diagnoses. Biologically, these tumors are characterized by a high degree of chromosomal instability and, frequently, mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. They are rapidly dividing and typically present with widespread peritoneal dissemination at the time of diagnosis. This subtype is most strongly associated with the fallopian tube origin theory and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndromes.

Low-grade serous carcinoma is a less common entity that behaves differently. It often arises from benign precursor lesions of the ovary, grows more slowly, and exhibits different molecular drivers, such as KRAS or BRAF mutations rather than p53 mutations. These tumors are less sensitive to standard chemotherapy compared to their high-grade counterparts, necessitating different management strategies.

Other significant epithelial subtypes include Endometrioid Carcinoma and Clear Cell Carcinoma. These are biologically distinct and are frequently associated with endometriosis. In these cases, endometrial tissue that has implanted on the ovary (endometrioma) undergoes malignant transformation over time. Clear cell carcinoma, in particular, is known for its resistance to conventional platinum-based chemotherapy and is more common in Asian populations. Mucinous Carcinoma is another rare subtype that often presents as large, localized masses. Distinguishing primary mucinous ovarian cancer from metastatic mucinous cancer arising from the gastrointestinal tract is a critical diagnostic challenge requiring advanced immunohistochemical staining.

While epithelial cancers dominate the landscape of adult ovarian malignancy, non-epithelial tumors represent a significant subgroup, particularly in younger women and adolescents. Germ Cell Tumors arise from the reproductive cells (eggs) within the ovary. These include dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumors, and immature teratomas. Unlike epithelial cancers, germ cell tumors often affect only one ovary and are diagnosed at an early stage. They are characterized by rapid growth but are exceptionally sensitive to chemotherapy, offering high cure rates even when the disease has spread, and often allowing for fertility-sparing surgery.

Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors originate from the connective tissue cells that hold the ovary together and produce hormones. Granulosa Cell Tumors are the most common type in this category. A defining feature of these tumors is their ability to secrete hormones, usually estrogen. This functional activity leads to specific clinical presentations, such as precocious puberty in young girls or postmenopausal bleeding in older women due to endometrial thickening. Because they grow slowly and produce symptoms early due to hormone excess, they are often detected at an early stage.

Another rare stromal tumor is the Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, which produces androgens (male hormones), leading to symptoms of virilization such as deepening of the voice or facial hair growth. The management of non-epithelial tumors differs markedly from that of epithelial cancers, often relying on different chemotherapy regimens (such as BEP: Bleomycin, Etoposide, Cisplatin) and requiring long-term follow-up for late recurrences, particularly with granulosa cell tumors, which can recur decades after initial diagnosis.

A defining characteristic of ovarian cancer is its mode of spread. While it can metastasize through the lymph nodes or bloodstream, its primary route of dissemination is transcoelomic—meaning across the body cavity. Malignant cells exfoliate from the surface of the ovary or fallopian tube and are carried by the physiological flow of peritoneal fluid. This fluid naturally circulates up the right side of the abdomen towards the diaphragm, driven by respiratory movements. Consequently, ovarian cancer cells often implant on the undersurface of the diaphragm, the liver surface, the omentum (a fatty apron hanging off the colon), and the bowel surfaces.

This widespread seeding is termed peritoneal carcinomatosis. The implanted cells form nodules that can range from microscopic seeds to large, bulky masses. The presence of these cancer cells irritates the abdominal lining, leading to an overproduction of peritoneal fluid while simultaneously blocking the lymphatic channels that drain it. This results in the accumulation of ascites—protein-rich fluid in the abdomen—a hallmark of advanced disease.

The biology of these implants is complex. The cancer cells must survive detachment from the primary tumor (anoikis resistance) and then successfully adhere to and invade the mesothelial lining of the peritoneum. The omentum, rich in adipocytes (fat cells), acts as a preferred sanctuary for ovarian cancer cells. The fat cells provide fatty acids to fuel the cancer’s rapid growth. Understanding this unique microenvironment is crucial for surgical planning, as the goal is to remove all visible disease from these widespread surfaces.

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies in the developed world. Its high mortality rate relative to its incidence is attributed to the lack of effective screening methods and the non-specific nature of early symptoms, leading to late-stage diagnosis. The epidemiology of the disease shows significant geographic variation, with higher incidence rates in North America and Northern Europe than in Africa and Asia. This distribution suggests a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, reproductive patterns, and environmental factors.

Age is the most significant demographic risk factor for sporadic epithelial ovarian cancer, with the majority of cases diagnosed in postmenopausal women between the ages of fifty-five and sixty-four. However, the landscape is shifting with the increasing recognition of hereditary cancer syndromes, which present at a younger age. The cumulative lifetime risk for a woman in the general population is approximately one to two percent, but this risk escalates dramatically for carriers of specific genetic mutations.

In recent years, global health initiatives have focused on defining the “ovarian cancer gap.” This refers to the disparity in survival outcomes between those with and without access to specialized care. Evidence strongly suggests that patients treated by gynecologic oncologists in high-volume centers, where maximal surgical effort and intraperitoneal therapies are available, have significantly better outcomes than those treated in general community settings. This underscores the need for centralized care pathways to manage this complex disease.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

ATG acts like a reset for the immune system. It contains antibodies that specifically target and kill T-lymphocytes, the white blood cells responsible for attacking the bone marrow in aplastic anemia. By wiping out these attacking cells, the stem cells are given a reprieve and can begin to grow again.

Eltrombopag was initially developed to boost platelet counts. However, it was discovered that it also stimulates the master hematopoietic stem cells. It is now added to immunosuppressive therapy to help kick-start the bone marrow, leading to faster and deeper recovery of blood counts.

Peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) contain more T-cells than bone marrow. While this is beneficial in fighting leukemia, in aplastic anemia, these extra T cells increase the risk of Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD). Bone marrow grafts are calmer and lead to better long-term quality of life for non-cancer patients.

Generally, yes. Because patients with aplastic anemia do not have cancer, they do not require the incredibly high, toxic doses of chemotherapy used to kill leukemia cells. The conditioning is gentler, focused mainly on immune suppression, which typically results in fewer immediate side effects and organ damage.

Immunosuppressive Therapy is not a quick fix. It typically takes 3 to 6 months to see a meaningful improvement in blood counts. Patience is key. During this time, the patient remains dependent on transfusions and careful infection prevention.

Many people are surprised to learn that lower back pain can signal ovarian cancer. This is true if the pain is new, keeps coming back,

Abdominal bloating and a visibly larger stomach are common signs of ovarian cancer. These symptoms are often mistaken for regular digestive issues. At Liv Hospital,

Many people think that ovarian cancer always leads to vaginal bleeding. But, the truth is more nuanced. We’re here to tell you that bleeding isn’t

Many women feel like they need to go to the bathroom all the time. But, it’s often because of ovarian cysts. These growths can make

Ovarian cancer is often called a ‘silent killer’ because its symptoms are not obvious and it’s often diagnosed late. Early detection is key to better

Ovarian cancer is a major threat to women’s health. Some groups face much higher risks because of their genes, family history, and lifestyle. It’s key

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)