Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

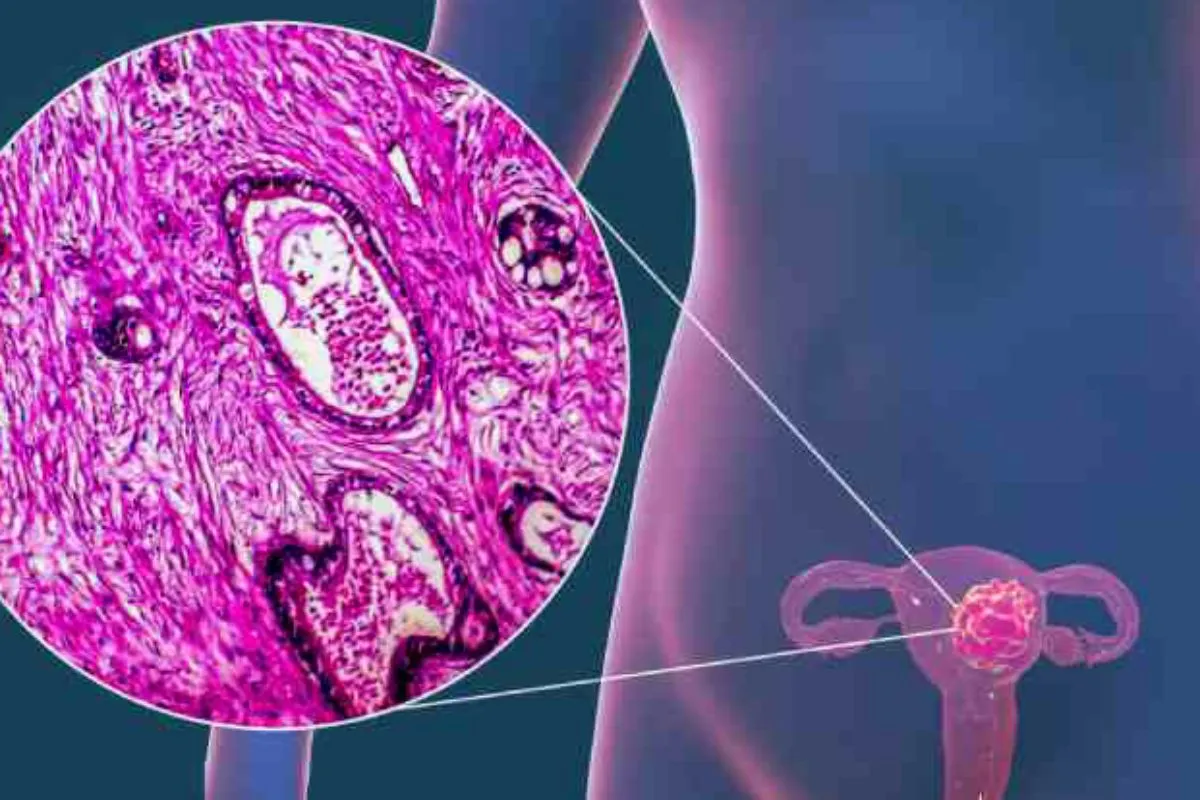

The cervix, also known as the cervix uteri, connects the uterus to the vagina. It is a cylindrical, fibromuscular structure located at the lower end of the uterus. The cervix acts as a barrier to protect the uterus from outside germs, but it also changes throughout a woman’s life, especially during menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth. Knowing how the cervix is built and how its cells work is key to understanding how cervical cancer develops, since the disease starts with changes in this area.

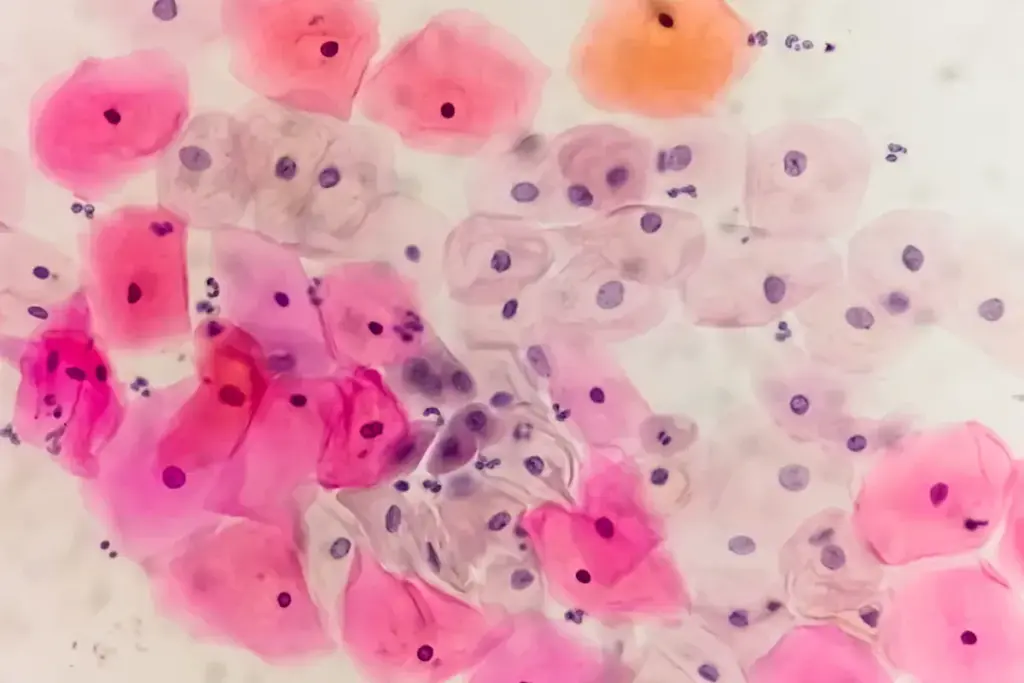

The cervix has two main types of tissue. The ectocervix, which can be seen during a gynecological exam, is covered by layers of squamous cells that protect it from the vagina’s acidic environment. The endocervix, which is the canal leading to the uterus, is lined with columnar cells that make mucus. Where these two cell types meet is called the squamocolumnar junction. This area moves as hormones like estrogen change during puberty, pregnancy, and menopause.

As the squamocolumnar junction moves, it creates an area called the transformation zone. Here, the delicate columnar cells are exposed to the vagina and change into stronger squamous cells, a process called metaplasia. Most cervical cancers start in this transformation zone because the young, dividing cells are more likely to be affected by viruses and genetic changes. That’s why this area is the main focus for screening and diagnosis.

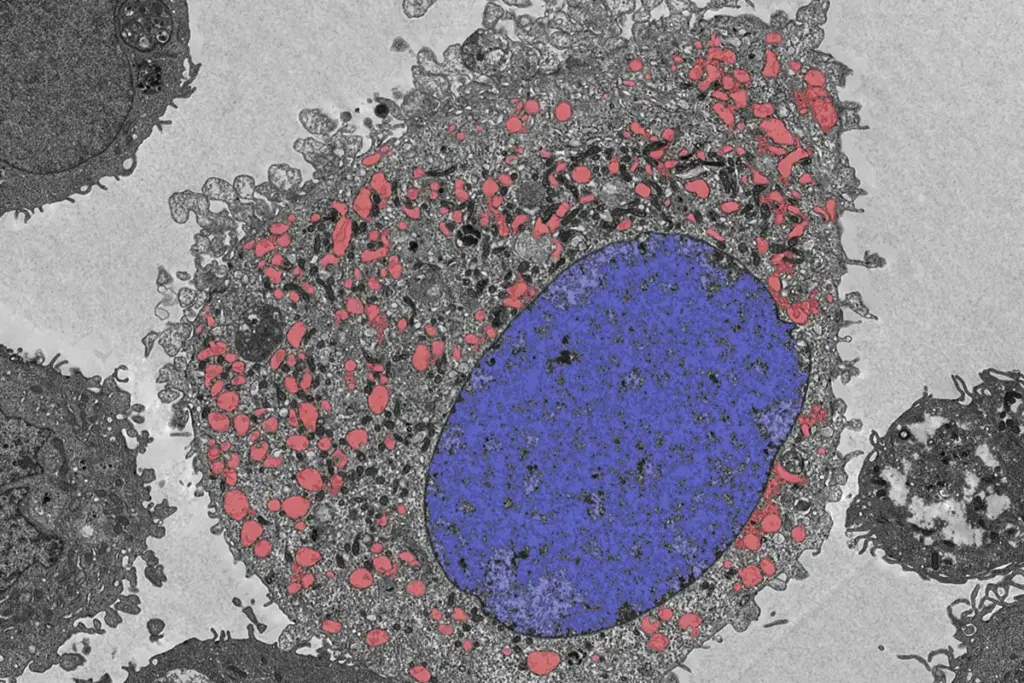

Cervical cancer develops in clear steps, starting from normal tissue and moving toward invasive cancer. This process is mainly caused by ongoing infection with high-risk types of Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Unlike many other cancers with unclear causes, the cause of cervical cancer is well known. The virus enters the basal cells of the cervix, usually through tiny breaks in the tissue. Once inside, the viral DNA can either stay separate or join with the cell’s own DNA.

A key step in cancer development is when the virus makes certain proteins, called E6 and E7. These proteins interfere with the cell’s natural defenses. E6 breaks down the p53 protein, which normally helps the cell get rid of damaged DNA. At the same time, E7 disrupts the pRb protein, which controls cell growth. Together, these changes let cells grow out of control and collect more genetic mistakes.

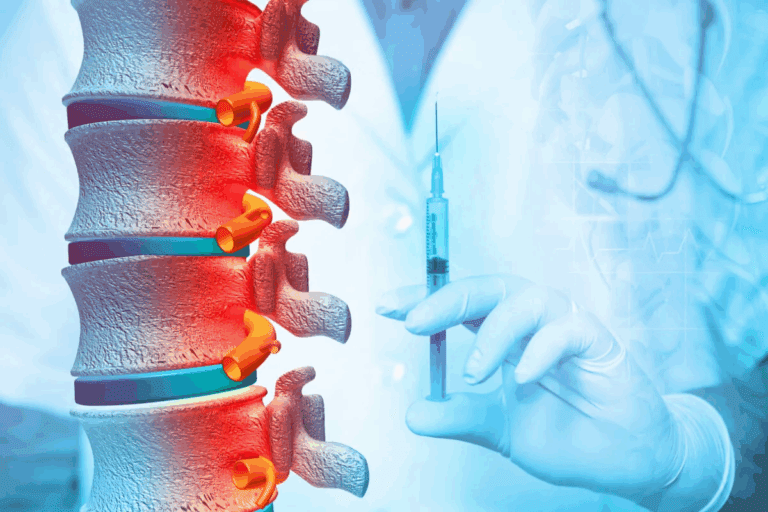

This process takes a long time, often many years. It goes through stages called Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN). CIN 1 is mild and often goes away on its own. CIN 2 and CIN 3 are more serious, with abnormal cells replacing the normal ones. If not treated, these cells can break through the basement membrane, a thin layer that separates the surface cells from deeper tissue. Once this happens, the cancer can spread to blood and lymph vessels and move to other parts of the body.

While the vast majority of cervical cancers are carcinomas, they are categorized into histological subtypes based on the cell of origin. Squamous Cell Carcinoma is the most prevalent subtype, accounting for approximately seventy to eighty percent of all cases. These tumors arise from the flat, skin-like cells of the ectocervix within the transformation zone. They are typically associated with HPV types 16 and 18 and follow the classic progression from CIN to cancer.

Adenocarcinoma is the second most common type, arising from the mucus-producing glandular cells of the endocervix. The incidence of adenocarcinoma has been rising in relative terms, partly because these lesions develop higher up in the cervical canal, making them harder to detect with traditional Pap smears, which sample the surface effectively but may miss glandular lesions deep in the canal. Adenocarcinomas can be more aggressive and have a higher propensity for distant metastasis and ovarian spread compared to squamous cell carcinomas.

Adenosquamous carcinoma is a mixed tumor containing both malignant squamous and glandular elements. It is generally considered to have a poorer prognosis than pure squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma. Rare neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix, such as small cell carcinoma, also exist. These are biologically distinct, behaving more like lung neuroendocrine tumors with early hematogenous spread and aggressive behavior, often requiring different treatment paradigms involving systemic chemotherapy similar to lung cancer protocols.

Cervical cancer shows a major gap in global health. In low- and middle-income countries, it is still a top cause of cancer deaths in women. This is mostly because there are not enough screening programs and limited access to early treatment. As a result, women often find out they have cancer at a late stage, when it is harder to cure. The impact goes beyond health, affecting families and communities since many women are in their most productive years when diagnosed.

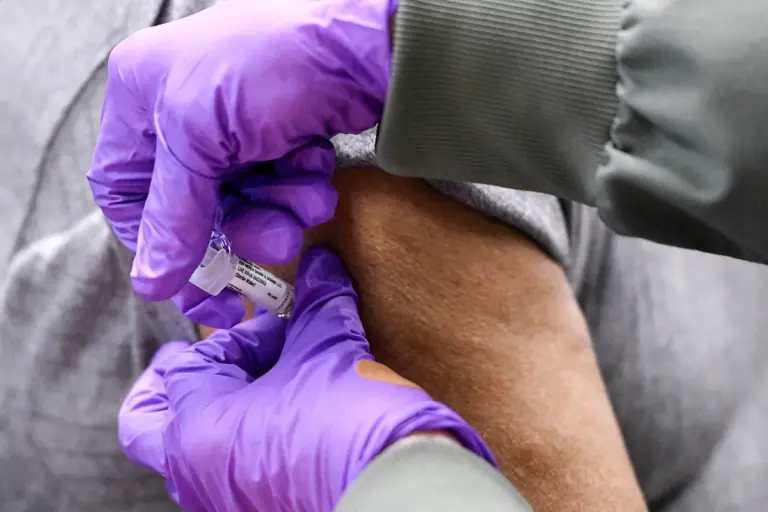

In contrast, high-income countries have seen a big drop in cervical cancer cases over the past 50 years. This is thanks to regular Pap smears and, more recently, HPV testing. These tests help find and treat pre-cancerous changes before they turn into cancer. The introduction of HPV vaccines has made an even bigger difference, with the hope of preventing most cases in the future.

Even with these improvements, there are still problems. Not everyone has access to vaccines, some people are hesitant to get vaccinated, and not all women are screened regularly. This means cervical cancer is still a risk, even in countries with good healthcare. Also, adenocarcinoma is harder to catch with older tests, so newer molecular tests are needed. The World Health Organization is working to eliminate cervical cancer by focusing on vaccination, screening, and treatment, treating it as a public health issue that can be solved.

Historically, the cervix was often conflated with the uterus in medical texts, but modern pathology has established it as a distinct biological entity with its own specific carcinogenesis. The understanding of cervical cancer has shifted from a morphological view—looking at cell shapes under a microscope—to a molecular view—identifying the presence of viral DNA. This shift has fundamentally changed clinical practice. We no longer look for “abnormal cells”; we look for the “cause” of the abnormality (HPV) to stratify risk.

This molecular understanding has also refined the classification of equivocal results. Terms like ASC-US (Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance) are now triaged using HPV testing to determine which women need invasive follow-up and which can be monitored. This prevents overtreatment of young women, whose immune systems will likely clear the virus, while ensuring that high-risk women are not missed.

Furthermore, the concept of “field cancerization” is relevant in the lower genital tract. Because the cervix, vagina, and vulva share a common embryological origin and are exposed to the same viral carcinogens, women with cervical neoplasia are at higher risk for vaginal and vulvar cancers. This necessitates a comprehensive approach to gynecologic health, viewing the lower genital tract as a unified system requiring holistic surveillance.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The transformation zone is a specific area on the cervix where the glandular cells of the inner canal change into the flat squamous cells of the outer cervix. This area is highly biologically active and is the specific site where Human Papillomavirus (HPV) preferentially infects cells. Consequently, it is the location where almost all cervical cancers and pre-cancerous lesions originate.

Squamous cell carcinoma starts in the flat, skin-like cells on the outer surface of the cervix and is the most common type. Adenocarcinoma begins in the glandular, mucus-producing cells inside the cervical canal. Adenocarcinoma is harder to detect with standard Pap smears because the cells are located higher up in the canal, and it is becoming more common than squamous cell carcinoma.

No, cervical cancer is not typically hereditary. Unlike breast or ovarian cancer, which inherited gene mutations like BRCA can drive, cervical cancer is driven by an acquired infection with high-risk HPV. While genetics may play a minor role in how effectively a person’s immune system fights the virus, the cancer itself is caused by the virus, not a family gene.

The basement membrane is a thin, fibrous layer that separates the surface lining (epithelium) of the cervix from the deeper tissue (stroma). As long as abnormal cells stay above this membrane, the condition is “pre-cancer” or carcinoma in situ. Once the cells break through the basement membrane, they are considered invasive cancer, as they can now reach blood vessels and lymph nodes.

It is considered preventable because it has a long pre-cancerous phase that can be detected and treated before it becomes invasive cancer. Furthermore, the primary cause, HPV infection, can be prevented through vaccination. The combination of vaccination to prevent disease and screening to remove pre-cancerous lesions makes it theoretically possible to eliminate this cancer.

Infectious Diseases

Infectious Diseases Infectious Diseases

Infectious Diseases Infectious Diseases

Infectious Diseases

Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)