Infectious diseases specialists diagnose and treat infections from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, focusing on fevers, antibiotics, and vaccines.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Food poisoning, also called foodborne illness or disease, is a major global health issue caused by eating or drinking contaminated food or drinks. Many people think of it as a minor problem, but it actually covers a wide range of infections and toxins that can affect the digestive system and, in serious cases, the nerves, kidneys, or immune system. At its core, food poisoning happens when harmful germs or chemicals enter the body through what we eat or drink.

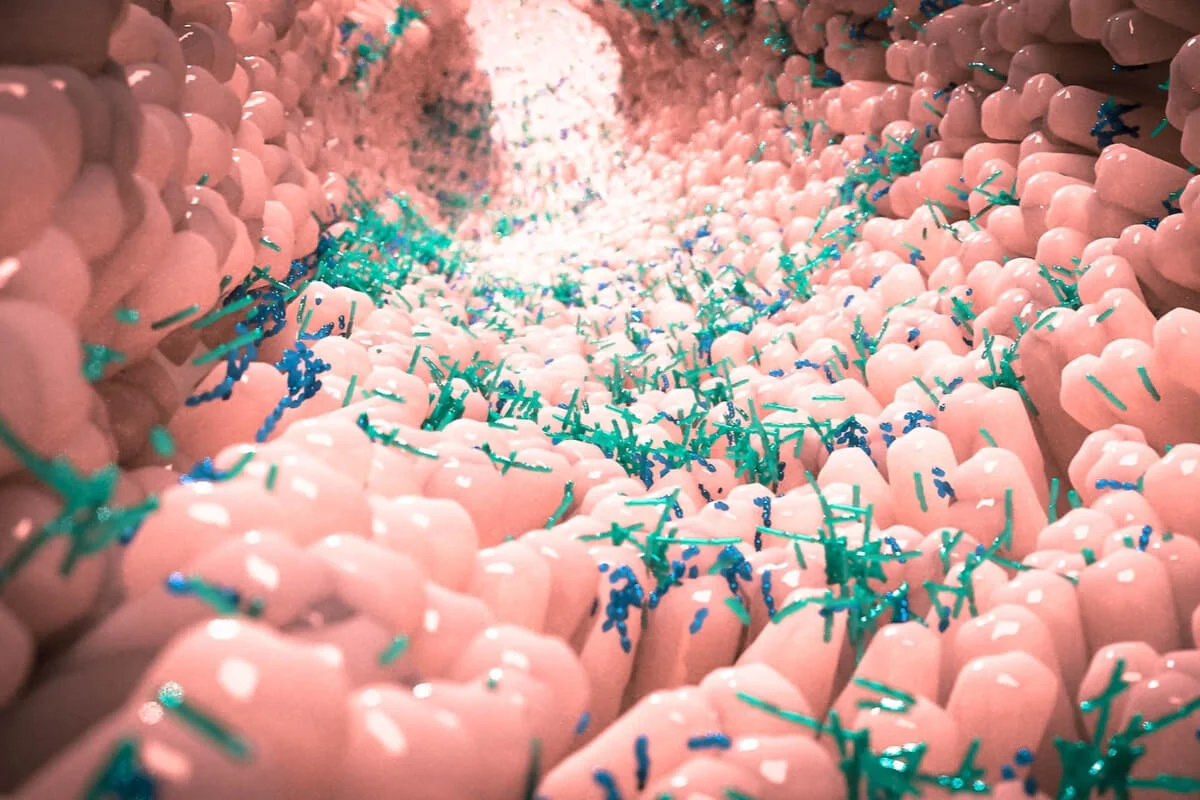

To understand food poisoning, it’s important to see the digestive system as more than just a way to process food. It acts as the main barrier between our bodies and the outside world. The gut is the body’s largest immune organ and is protected by strong defenses like stomach acid, digestive enzymes, bile, and a physical lining. It also contains trillions of helpful bacteria, known as the gut microbiome, which compete with harmful germs. Food poisoning happens when a germ or toxin gets past these defenses and causes illness.

There are clear definitions in this area. A foodborne infection happens when someone eats live germs—bacteria, viruses, or parasites—that survive the stomach and start growing in the intestines or other tissues. This usually takes some time, called the incubation period, before symptoms appear. On the other hand, foodborne intoxication happens when a person eats toxins already made by bacteria (like Staphylococcus aureus) or found naturally in food (like some seafood toxins). In these cases, the germs don’t need to be alive or present when you eat the food; the toxin itself causes quick and sometimes severe symptoms.

Food poisoning has many causes. The main sources are biological germs and chemical contaminants. Most sudden outbreaks are caused by biological germs like bacteria, viruses, and parasites.

Food poisoning affects people everywhere, but not equally. Both rich and poor countries face this problem, though the germs and ways it spreads can differ. In developing countries, foodborne illness is closely tied to unsafe water, poor sanitation, and poverty. Repeated infections can cause malnutrition and even stunt children’s growth and development.

Even in countries with good sanitation, food poisoning is still a problem because of the way food is produced and distributed. If one factory or farm has contaminated food, it can cause outbreaks in many places at once. The popularity of ready-to-eat foods, raw produce, and imported items also brings new risks, as unfamiliar germs can be introduced to people who have not been exposed to them before.

Surveillance systems play a critical role in defining the scope of the problem. Public health agencies use advanced genomic sequencing to “fingerprint” bacteria from sick patients and match them to strains found in contaminated food products. This molecular epidemiology has revealed that what was once thought to be sporadic, unrelated cases of stomach flu are often part of diffuse, low-level outbreaks linked to widely distributed products like flour, spices, or leafy greens.

A crucial component of the overview of food poisoning is the role of the host. Not everyone who consumes contaminated food becomes ill. This variability is governed by the pathogen’s “infectious dose” and the host’s susceptibility. The stomach acid barrier serves as the first line of defense; individuals taking proton pump inhibitors (acid-suppressing medications) or those with achlorhydria are often more susceptible to bacterial infections such as Salmonella or Campylobacter because the acid barrier is reduced.

Furthermore, the integrity of the resident gut microbiome is a significant determinant of resistance. A diverse and robust community of healthy gut bacteria provides “colonization resistance,” physically occupying the niches on the intestinal wall and producing antimicrobial peptides that deter pathogens. Recent research suggests that disrupting this microbiome—through antibiotic overuse, poor diet, or stress—creates an environment where foodborne pathogens can more easily establish a foothold. This biological context shifts the definition of food poisoning from a simple event of “bad food” to a complex interaction between the intruder and the host’s ecosystem.

Humanity’s relationship with foodborne illness is as old as the species itself. The transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agrarian civilizations created the first major amplification systems for foodborne disease, as humans began living in proximity to domesticated animals and stored grain in ways that attracted pests. Historical records are replete with accounts of “flux” and “dysentery” decimating armies and populations.

The scientific understanding of food poisoning began to crystallize in the 19th century with the germ theory of disease. The identification of specific bacteria as the causative agents of spoilage and illness led to revolutionary interventions such as pasteurization, canning, and refrigeration. These technologies drastically reduced the incidence of botulism and typhoid fever. However, the 20th and 21st centuries have introduced new challenges, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the emergence of new pathogens. The narrative of food poisoning is one of constant evolution, in which human innovation in food production creates new ecological niches for pathogens to exploit, necessitating continuous advancement in our biological and medical understanding.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

A foodborne infection is caused by swallowing live bacteria or viruses that grow inside your body and cause illness. Food intoxication, or food poisoning in the strictest sense, is caused by swallowing toxins that were already produced by bacteria in the food before it was eaten. Intoxication usually makes you sick much faster than an infection.

The term “stomach flu” is a common misnomer. Influenza (the flu) is a respiratory virus that attacks the lungs. What people call stomach flu is usually viral gastroenteritis, often caused by Norovirus. While this can be spread through person-to-person contact, it is frequently transmitted through contaminated food, making it a form of food poisoning.

Susceptibility varies based on individual immune systems, stomach acid levels, and the status of their gut microbiome. Additionally, contamination in food is not always evenly distributed; one portion of a dish might contain a high bacterial load, while another portion has very little.

While most people recover fully, some foodborne illnesses can lead to chronic health issues. These can include kidney failure (from E. coli), chronic arthritis, brain and nerve damage (from Listeria or Campylobacter), or irritable bowel syndrome that persists long after the infection has cleared.

Rarely. Spoilage bacteria that make food smell or taste bad are often different from pathogenic bacteria that make you sick. Dangerous pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria typically do not change the taste, smell, or appearance of the food, which is why safety practices are so important.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)