Last Updated on October 21, 2025 by mcelik

Sickle cell disease affects millions worldwide, causing significant health complications. At its core, this condition is triggered by a specific genetic alteration.

We know that sickle cell disease is caused by a point mutation in the HBB gene. This gene codes for the beta-globin subunit of hemoglobin. This mutation leads to the production of abnormal hemoglobin, known as sickle hemoglobin or HbS.

This genetic change results in the disease’s characteristic symptoms. These include anemia, infections, and episodes of pain. Understanding the genetic basis of sickle cell anemia is crucial for developing effective treatments.

Key Takeaways

- Sickle cell disease is caused by a point mutation in the HBB gene.

- The mutation affects the production of the beta-globin subunit of hemoglobin.

- Abnormal hemoglobin production leads to the disease’s characteristic symptoms.

- Understanding the genetic cause is key to developing effective treatments.

- Research into the genetic mutation continues to advance treatment options.

The Nature and Impact of Sickle Cell Disease

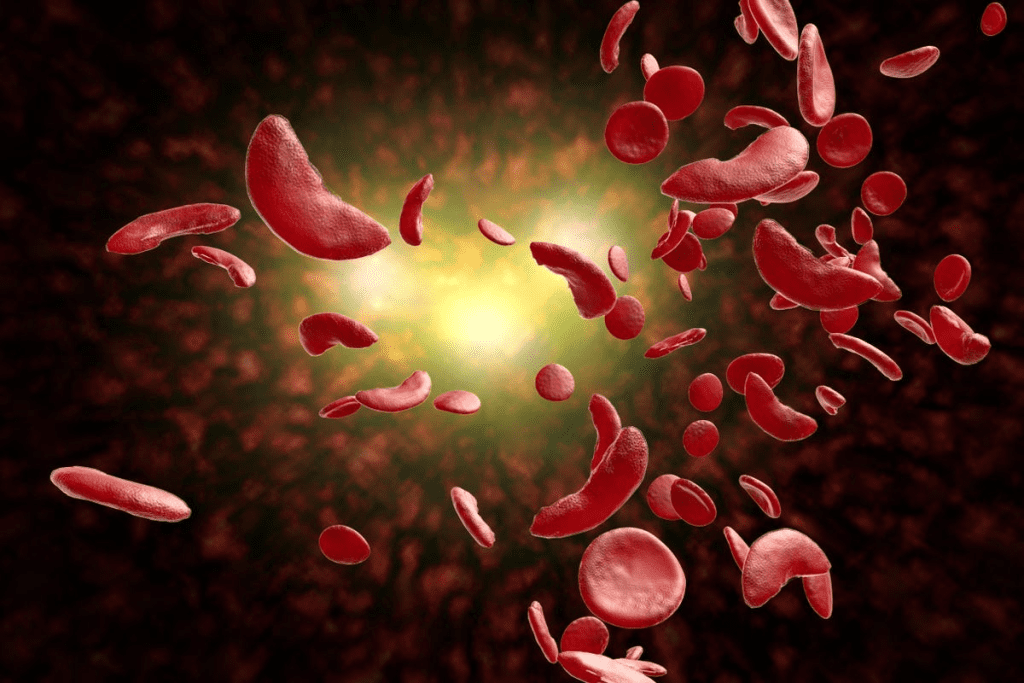

It’s important to understand sickle cell disease to tackle its effects. This genetic disorder changes how red blood cells are made. It makes them sickle-shaped, leading to health problems like pain, anemia, and infections.

The symptoms of sickle cell disease vary widely. It can cause both sudden and long-term problems. These issues affect many parts of the body.

Clinical Manifestations of Sickle Cell Disease

The symptoms of sickle cell disease are varied and can be severe. Acute complications include pain crises, which happen when sickled red blood cells block blood vessels. This causes tissue damage. Chronic complications result from repeated damage to organs.

- Pain crises

- Anemia

- Increased risk of infections

- Organ damage

Global Distribution and Prevalence Rates

Sickle cell disease is found worldwide, especially where malaria was common. It’s most common in sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean, and parts of India.

| Region | Prevalence Rate |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 in 100 births |

| Mediterranean | 1 in 400 births |

| India (certain regions) | 1 in 300 births |

The disease is more common in areas where malaria was once a big problem. This shows how genetics, environment, and disease interact.

The Sickle Cell Mutation: A Single Nucleotide Change

Learning about sickle cell disease starts with the HBB gene and its mutation. The HBB gene tells our bodies how to make a key protein in red blood cells. This protein carries oxygen to all parts of our body.

Normal Hemoglobin Structure and Function

Hemoglobin is made of four parts: two alpha-globin chains and two beta-globin chains. This structure lets red blood cells move freely through blood vessels. The beta-globin chains are especially important because they are changed by the sickle cell mutation.

When the HBB gene works right, it makes Hemoglobin A (HbA). This hemoglobin is good at carrying oxygen. It works well with alpha-globin to transport oxygen throughout our body.

The HBB Gene on Chromosome 11

The HBB gene is found on chromosome 11. Changes in this gene can cause sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies. The gene is key for making the beta-globin subunit of hemoglobin. Any change in it can lead to bad hemoglobin.

| Gene | Chromosome Location | Protein Product |

| HBB | 11 | Beta-globin |

The GAG to GTG Substitution

The sickle cell mutation is a single change in the HBB gene. It swaps glutamic acid for valine at the sixth spot of the beta-globin chain. This happens because GAG (glutamic acid) turns into GTG (valine).

This change makes bad hemoglobin, called Hemoglobin S (HbS). The switch from glutamic acid to valine makes hemoglobin stick together when there’s not enough oxygen. This causes red blood cells to take on a sickle shape.

“The substitution of valine for glutamic acid at position 6 of the beta-globin chain is the fundamental cause of sickle cell disease, leading to the polymerization of deoxygenated hemoglobin S and the resultant sickling of red blood cells.”

Knowing about this genetic change is key for diagnosing and treating sickle cell disease. This single change affects how hemoglobin works. It impacts the health and well-being of those with the disease.

Point Mutation: The Genetic Mechanism Behind Sickle Cell Disease

The root cause of sickle cell disease is a point mutation. This mutation changes the genetic code for hemoglobin. It leads to the production of abnormal hemoglobin.

We will explore the different types of genetic mutations and their effects on protein function. We will focus on missense mutations like the one responsible for sickle cell disease.

Types of Genetic Mutations

Genetic mutations are changes in the DNA sequence. They can result in various health conditions. There are several types of mutations, including:

- Point mutations: A change in a single nucleotide base

- Frameshift mutations: Insertions or deletions of nucleotides that alter the reading frame

- Chromosomal mutations: Changes in the structure or number of chromosomes

Point mutations, such as the one causing sickle cell disease, involve a single nucleotide change. This change can significantly impact protein function.

Missense Mutations and Their Effects

A missense mutation occurs when a point mutation results in a codon that codes for a different amino acid. In sickle cell disease, this mutation changes glutamic acid to valine at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain.

This change causes hemoglobin to polymerize under low oxygen conditions. This results in the characteristic sickle shape of red blood cells.

Why Single Nucleotide Changes Can Be Devastating

A single nucleotide change can have profound effects on protein function, as seen in sickle cell disease. The severity of the impact depends on the location and nature of the mutation.

In some cases, a single nucleotide change may have minimal effects. In others, it can lead to significant changes in protein structure and function. This can result in disease.

Understanding the genetic mechanism behind sickle cell disease is crucial. It is important for developing effective treatments and management strategies.

From Genetic Code to Protein: How the Mutation Alters Hemoglobin

The sickle cell mutation changes the genetic code for hemoglobin, leading to abnormal hemoglobin S. This happens because of a point mutation in the HBB gene. This gene codes for the beta-globin subunit of hemoglobin. Knowing how this mutation affects hemoglobin’s structure and function is key to understanding sickle cell disease.

The Glutamic Acid to Valine Substitution

The mutation swaps glutamic acid with valine at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain. This switch from a hydrophilic glutamic acid to a hydrophobic valine greatly affects hemoglobin’s properties. The change creates a sticky patch on the hemoglobin molecule’s surface. This can interact with other similar hemoglobin molecules under certain conditions.

Structural Changes in Hemoglobin S

With valine instead of glutamic acid, we get hemoglobin S (HbS). HbS has different properties than normal hemoglobin (HbA). Under low oxygen, HbS molecules form long fibers. This distorts the red blood cell into a sickle shape.

This polymerization is reversible but repeated episodes cause permanent damage to red blood cells.

Polymerization of Abnormal Hemoglobin

The polymerization of HbS is crucial in sickle cell disease’s pathogenesis. When HbS is deoxygenated, the hydrophobic valine residues interact. This leads to the formation of polymers.

These polymers form long fibers that make the red blood cell rigid and sickle-shaped. Sickled red blood cells are more likely to be destroyed. They can also block small blood vessels, causing the symptoms of sickle cell disease.

| Property | Normal Hemoglobin (HbA) | Hemoglobin S (HbS) |

| Amino Acid at Position 6 | Glutamic Acid | Valine |

| Charge at Position 6 | Negative | Nonpolar |

| Polymerization Tendency | Low | High under low oxygen conditions |

| Effect on Red Blood Cell | Flexible, normal shape | Rigid, sickled shape under low oxygen |

Is Sickle Cell Disease Dominant or Recessive?

Understanding if sickle cell disease is dominant or recessive is key. It’s inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. This means a person must get two mutated alleles, one from each parent, to have the disease.

Principles of Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

The disease-causing gene is on a non-sex chromosome. People with sickle cell disease have two mutated HBB genes, one from each parent. Carriers have one normal and one mutated gene. They usually don’t show symptoms but can pass the mutated gene to their kids.

Carrier Status and Sickle Cell Trait

Those with one mutated gene are carriers and have sickle cell trait. They often don’t show symptoms but can pass the mutated gene to their children. When two carriers have kids, there’s a 25% chance each child will have sickle cell disease.

Incomplete Dominance in Hemoglobin Disorders

In hemoglobin disorders like sickle cell disease, incomplete dominance is important. Carriers may show some effects under certain conditions, like intense exercise. This shows that normal and sickle alleles don’t completely dominate each other.

| Genotype | Phenotype | Condition |

| Normal/Normal | Normal | No disease |

| Normal/Sickle | Carrier | Sickle Cell Trait |

| Sickle/Sickle | Affected | Sickle Cell Disease |

Inheritance Patterns of Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle cell anemia is passed down in an autosomal recessive pattern. This means both parents must carry the mutated gene. This pattern affects how likely a child is to get the disease or carry the gene.

Punnett Square Analysis for Sickle Cell Inheritance

A Punnett square helps predict a child’s genotype based on their parents’. For sickle cell anemia, it shows the chance of a child getting two mutated HBB genes. This causes the disease.

Imagine both parents carry the sickle cell gene (HbS). They have the genotype HbAS, with one normal and one sickle cell gene. A Punnett square can show the possible genotypes of their kids.

| Mother’s Genes | Father’s Genes | Offspring Genotype | Probability |

| HbA | HbA | HbAA | 25% |

| HbA | HbS | HbAS | 50% (combined) |

| HbS | HbA | HbAS | – |

| HbS | HbS | HbSS | 25% |

Probability Calculations for Affected Offspring

The Punnett square shows a 25% chance of a child getting two normal genes (HbAA). There’s a 50% chance they’ll be a carrier (HbAS). And a 25% chance they’ll get two mutated genes (HbSS), leading to sickle cell anemia.

Knowing these chances is key for genetic counseling. It helps families plan better.

Co-inheritance with Other Hemoglobin Disorders

Sickle cell anemia can also come with other hemoglobin disorders like HbC or beta-thalassemia. This can lead to conditions like HbSC disease or sickle-beta-thalassemia. These have different symptoms.

For example, HbSC disease might be milder than HbSS. But it still causes health problems. Knowing about co-inheritance is important for correct diagnosis and treatment.

How Common Is Sickle Cell Anemia in Different Populations

Sickle cell anemia is a big health issue worldwide. Its spread depends on genetics, where people live, and who they are. We’ll look at how it impacts different groups globally.

Prevalence in African and Mediterranean Populations

Sickle cell disease hits hard in African and Mediterranean communities. In some African nations, up to 30% of people carry the sickle cell trait. This is because malaria, which was once common, helped those with the trait survive better.

- In Nigeria, about 2.5% of babies are born with sickle cell disease.

- In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the numbers are similar.

Sickle Cell Disease in the United States

In the U.S., sickle cell disease affects 1 in 500 African Americans. About 1 in 12 African Americans have the sickle cell trait. It also affects Hispanic/Latino people, especially those from the Caribbean and Central America.

Global Distribution and Migration Patterns

Migration has changed where sickle cell disease is found. When people move, they take their genes with them. This changes the disease’s spread in new places.

- People moving from high-risk areas to lower-risk ones have spread sickle cell disease worldwide.

- Places with few cases are now seeing more due to migration.

Knowing about these trends helps health planners. It ensures care reaches those who need it most everywhere.

Evolutionary Advantage: The Malaria Connection

The link between sickle cell trait and malaria resistance is truly fascinating. In places where malaria has been a big problem, the sickle cell trait has helped people survive. This has made the sickle cell allele more common in these areas.

Geographic Correlation with Malaria Endemicity

Research shows a clear link between sickle cell trait and malaria-prone areas. This isn’t just a coincidence. It shows how the sickle cell trait helps protect against malaria.

In places where malaria is common, more people have the sickle cell allele. This is especially true in sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean, and South Asia. These areas have long struggled with malaria.

Mechanism of Malaria Resistance in Carriers

The sickle cell trait’s role in fighting malaria is complex. But studies say it makes it hard for malaria parasites to grow in red blood cells of carriers.

Specifically, hemoglobin S (HbS) in red blood cells hampers the growth of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. This leads to less severe malaria in people with the sickle cell trait. It gives them an edge in survival.

Balanced Polymorphism in Human Evolution

The sickle cell allele is more common in malaria-prone areas. This is due to balanced polymorphism. Being a carrier (heterozygous) offers malaria resistance, balancing out the drawbacks of being homozygous.

This balance is key to understanding human evolution. It shows how genetic traits can stick around because they offer survival benefits, even if they’re harmful in some genotypes.

| Region | Malaria Endemicity | Sickle Cell Trait Prevalence |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | High | High |

| Mediterranean | Moderate | Moderate |

| South Asia | Variable | Variable |

The table shows a clear link between malaria and sickle cell trait prevalence. Where malaria is common, so is the sickle cell trait. This highlights its evolutionary advantage.

Diagnosing Sickle Cell Disease: From Genetic Testing to Newborn Screening

Advanced genetic testing has made diagnosing sickle cell disease more accurate and timely. We now have many tools to detect it early. This helps in managing the condition better.

Diagnosing sickle cell disease involves several methods. Early diagnosis is crucial for effective management. It improves the quality of life for those affected.

Hemoglobin Electrophoresis and Blood Tests

Hemoglobin electrophoresis is a traditional method for diagnosing sickle cell disease. It separates hemoglobin types by electrical charge. This helps identify abnormal hemoglobin S. Blood tests, like complete blood counts (CBC), also check the patient’s health and detect abnormalities.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis is great because it can spot sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies. It’s a reliable method used for decades.

DNA Analysis Techniques

DNA analysis has changed how we diagnose sickle cell disease. Methods like PCR and genetic sequencing find the HBB gene mutation. These are very accurate and can be used before birth.

DNA analysis is key for finding sickle cell trait carriers. This is important for genetic counseling.

Universal Newborn Screening Programs

Newborn screening programs are key for early sickle cell disease detection. They test newborns for the disease soon after birth. Early detection leads to better outcomes.

Many countries, including the United States, have universal newborn screening. It has greatly reduced sickle cell disease-related morbidity and mortality.

Clinical Consequences of the Sickle Cell Mutation

The sickle cell mutation has serious effects on patients. It can lead to both sudden problems and long-term damage to organs. This greatly affects their quality of life.

Acute Complications: Pain Crises and Infections

Pain crises, or vaso-occlusive crises, are common in sickle cell disease. They happen when sickled red blood cells block blood vessels. This causes pain and tissue damage. Managing pain crises well is key to avoiding more problems and improving health.

People with sickle cell disease also face a higher risk of infections. Their spleen, which helps fight off infections, is often damaged. This makes them more likely to get infections, especially from bacteria that are covered in a protective layer.

- Sepsis

- Pneumonia

- Meningitis

These infections can be very serious and even deadly. So, it’s important to take steps to prevent them. This includes getting vaccinated and taking antibiotics as needed.

Chronic Organ Damage

Long-term, sickle cell disease can damage organs. The kidneys, liver, heart, and lungs are often affected.

Chronic kidney disease is a big worry. It can lead to needing dialysis or a kidney transplant. The heart also works harder because of chronic anemia. This can cause heart failure.

It’s crucial for doctors to understand these effects. This way, they can give better care. And patients can better manage their condition.

Current Treatment Approaches for Sickle Cell Disease

Managing sickle cell disease needs a mix of treatments to ease symptoms and boost life quality. There’s no cure yet, but many options help manage its effects and better patient results.

Hydroxyurea: Modifying the Effects of the Mutation

Hydroxyurea is a drug that cuts down on painful crises and might lower blood transfusion needs. It boosts fetal hemoglobin production, easing the disease’s impact. Studies show it greatly improves life quality for those with sickle cell disease.

Benefits of Hydroxyurea:

- Reduces frequency of painful crises

- Decreases need for blood transfusions

- May reduce risk of complications

Blood Transfusions and Iron Chelation

Blood transfusions treat anemia and lower sickle cell disease risks. They boost oxygen to tissues and organs. But, they can cause iron overload, needing iron chelation therapy to remove excess iron.

| Treatment | Purpose | Benefits |

| Blood Transfusions | Treat anemia, reduce complications | Improves oxygen delivery, reduces risk of stroke |

| Iron Chelation Therapy | Remove excess iron | Reduces risk of iron overload complications |

Pain Management Strategies

Pain management is key in treating sickle cell disease. It includes medicines and non-medical methods like hydration and rest. Each patient’s pain needs a tailored approach, considering their personal preferences.

“Pain is a hallmark of sickle cell disease, and managing it effectively is crucial to improving the quality of life for patients.”

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only cure for sickle cell disease. It replaces the patient’s bone marrow with healthy stem cells. Though it offers a cure, it comes with risks like graft-versus-host disease and mortality.

We’re always looking to improve sickle cell disease treatments. As research grows, we’ll see new therapies to manage this complex condition.

Gene Therapy and Emerging Treatments Targeting the Sickle Cell Mutation

The treatment for sickle cell disease is on the verge of a big change. This is thanks to gene therapy and new treatments. We’re learning more about the genetic cause of sickle cell disease. This knowledge is helping us find new ways to treat it.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Approaches

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is a very promising new treatment. It can change the HBB gene that causes sickle cell disease. This could lead to a real cure by fixing the single mutation that causes the disease.

Key benefits of CRISPR-Cas9 include:

- Precision in editing the genome

- Potential for a one-time treatment

- Ability to target the root cause of the disease

Fetal Hemoglobin Induction Strategies

Another new strategy is to increase fetal hemoglobin (HbF). HbF can help reduce the effects of sickle cell disease. Scientists are looking into ways to make more HbF in adults, like with medicine or gene therapy.

The potential benefits of HbF induction include:

- Reduced frequency of pain crises

- Decreased risk of complications

- Improved quality of life for patients

Current Clinical Trials and Research Directions

Many clinical trials are testing gene therapy and other new treatments for sickle cell disease. These trials are important for learning more about these new therapies. They help us get closer to bringing these treatments to patients.

Ongoing research directions include:

- Optimizing gene editing techniques

- Developing more effective conditioning regimens for gene therapy

- Exploring combination therapies to enhance treatment outcomes

The future of treating sickle cell disease looks bright. Gene therapy and other new approaches are making progress. While there are still challenges, these advancements give hope to those affected by the disease.

Conclusion: Understanding the Genetic Basis of Sickle Cell Disease

Knowing the genetic cause of sickle cell disease is key for diagnosis and treatment. A single change in the HBB gene leads to abnormal hemoglobin. This causes the disease’s symptoms.

We’ve looked at sickle cell disease’s nature and its genetic cause. It’s caused by a specific mutation that changes hemoglobin’s structure. This knowledge helps doctors treat the disease and helps patients understand it.

Today, treatments like hydroxyurea and blood transfusions help manage symptoms. New treatments like gene therapy and CRISPR-Cas9 might cure it. By understanding sickle cell disease’s genetics, we can keep improving care for patients.

FAQ

What type of mutation causes sickle cell disease?

Sickle cell disease comes from a point mutation in the HBB gene. This gene codes for a part of hemoglobin. The mutation changes glutamic acid to valine at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain.

Is sickle cell disease dominant or recessive?

Sickle cell disease is recessive. A person needs two copies of the mutated HBB gene to have the disease.

How is sickle cell anemia inherited?

Sickle cell anemia follows an autosomal recessive pattern. Carriers have one normal and one mutated HBB gene. They usually don’t show symptoms but can pass the mutated gene to their kids.

What is the genetic mechanism behind sickle cell disease?

The disease is caused by a missense mutation in the HBB gene. This leads to abnormal hemoglobin S. Under low oxygen, this hemoglobin causes red blood cells to sickle.

How common is sickle cell anemia in different populations?

Sickle cell anemia is common in Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. It’s linked to areas where malaria was common. Carriers have a survival advantage against malaria.

What is the evolutionary advantage of the sickle cell trait?

The sickle cell trait helps protect against severe malaria. This has made it more common in malaria-prone areas.

How is sickle cell disease diagnosed?

Doctors use hemoglobin electrophoresis, blood tests, and DNA analysis to diagnose it. Newborn screening also helps find it early.

What are the clinical consequences of sickle cell disease?

The disease can cause pain crises and infections. It also leads to chronic damage in organs. It affects many systems and lowers quality of life.

What are the current treatment approaches for sickle cell disease?

Treatments include hydroxyurea to reduce pain crises and blood transfusions. Pain management and stem cell transplantation are also options.

What emerging treatments are being developed for sickle cell disease?

New treatments include gene therapy and ways to increase fetal hemoglobin. These aim to fix the disease’s root cause.

Is sickle cell disease autosomal recessive?

Yes, it’s an autosomal recessive condition. A person needs two mutated HBB genes to have the disease.

What gene is affected by sickle cell disease?

The HBB gene, which makes a part of hemoglobin, is affected by the mutation.

What type of genetic mutation causes sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell anemia is caused by a missense mutation in the HBB gene. This changes glutamic acid to valine.

References

- Afranie-Sakyi, J. A., et al. (2025). The mortality of adults with sickle cell disease at a tertiary center: A retrospective review. British Journal of Haematology. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39748504/