A cystoscope is a specialized medical optical instrument designed for the visual examination of the lower urinary tract. It functions as a viewing tube that allows a urologist to look directly inside the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body) and the urinary bladder. The device solves the diagnostic “blind spot” of external imaging; while Ultrasound or CT scans can show the shape or size of the bladder, they often cannot detect subtle changes in the lining, small tumors, or sources of bleeding. The cystoscope bridges this gap by providing a direct, high-definition internal view.

The primary purpose of cystoscopy is diagnostic clarity. It is the gold standard for investigating symptoms such as hematuria (blood in the urine), recurrent urinary tract infections, unexplained pelvic pain, and urinary blockage. Beyond diagnosis, the cystoscope serves as a conduit for therapeutic intervention, allowing physicians to remove small stones, treat bladder tumors, or stop bleeding without the need for open surgery.

How the Cystoscope Works?

The technology behind a cystoscope relies on advanced optics, illumination, and fluid mechanics to create a clear visual field within a collapsed organ.

Optical Transmission and Lighting

Whether the device is rigid or flexible, the core mechanism involves a system of lenses or fiber-optic bundles.

- Light Source: A powerful light source (typically LED or Xenon) is connected to the scope via a fiber-optic cable. This light travels down the length of the instrument to illuminate the interior of the dark bladder cavity.

- Image Capture: In modern “video cystoscopes,” a miniature digital chip at the tip captures high-resolution video and transmits it to a large monitor. This magnification allows the physician to identify mucosal abnormalities as small as a pinhead.

Fluid Irrigation System

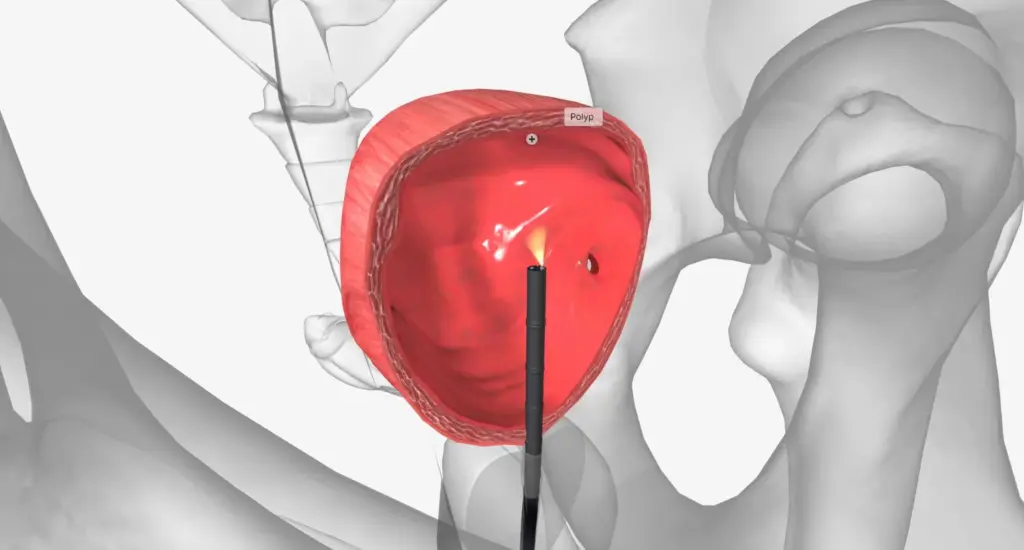

The bladder is a muscular sac that is naturally collapsed when empty. To inspect the lining, the walls must be pushed apart.

- Distension: The cystoscope features a dedicated channel that connects to a sterile saline (saltwater) bag.

- Continuous Flow: As the scope enters the bladder, the physician controls a valve to flood the organ with saline. This fluid expands the bladder like a balloon, smoothing out the folds (rugae) of the lining. This ensures that no tumor or stone can hide between the wrinkles of the bladder wall.

The Working Channel

A crucial mechanical feature is the “working channel.” This hollow port runs alongside the optical lenses. It allows the insertion of thin, specialized instruments such as:

- Biopsy Forceps: To snip tiny samples of suspicious tissue.

- Laser Fibers: To break up stones or burn away tumor tissue.

- Graspers: To latch onto and retrieve foreign bodies or stone fragments.

Clinical Advantages and Patient Benefits

Cystoscopy offers distinct clinical advantages that make it indispensable in urology, particularly when compared to non-invasive imaging or open surgical exploration.

Direct Visualization vs. Shadow Imaging

Imaging tests like X-rays or Ultrasounds rely on “shadows” and density differences. They can miss flat lesions, such as Carcinoma In Situ (CIS), a high-grade, aggressive bladder cancer that spreads along the surface lining. Cystoscopy allows the doctor to see the actual color and texture of the tissue. Red patches, velvet-like textures, or small papillary growths are immediately visible to the naked eye, leading to earlier and more accurate diagnoses.

The Shift to Flexible Cystoscopy

Historically, cystoscopes were rigid metal tubes, which could be uncomfortable, especially for male patients due to the length and curvature of the male urethra. Modern Flexible Cystoscopy has revolutionized patient comfort.

- Anatomical Conformity: The tip of a flexible cystoscope can bend and rotate up to 270 degrees. This allows the instrument to navigate the natural curves of the urethra without friction and lets the doctor look backward at the bladder neck (retroflexion), an area previously hard to see.

- Office-Based Procedure: Because flexible scopes cause minimal trauma, the procedure is routinely performed in a standard clinic room with only local anesthetic jelly, eliminating the risks and recovery time associated with general anesthesia or hospital admission.

Immediate Intervention

If a problem is found, it can often be fixed immediately. For example, if a urologist sees a stent that needs removal or a small stone blocking the flow, they can utilize the working channel to resolve the issue in seconds. This “See and Treat” capability saves the patient from scheduling a second procedure.

Targeted Medical Fields and Applications

While the cystoscope is the primary tool of the Urology department, its findings are critical for Oncology and Urogynecology.

Urologic Oncology (Bladder Cancer)

- Surveillance: Bladder cancer has a high rate of recurrence. Patients with a history of bladder tumors require regular “check-up” cystoscopies (often every 3 to 6 months) to ensure the cancer has not returned. This is the only reliable method for long-term monitoring.

- Staging: It helps determine the size, location, and number of tumors, which dictates whether a patient needs minor endoscopic scraping or major surgery.

Functional Urology

- Obstruction Analysis: For men with enlarged prostates (BPH), cystoscopy helps visualization of the prostatic urethra to determine how much the prostate is blocking the urinary channel.

- Stricture Diagnosis: It identifies scar tissue (strictures) that narrows the urethra and restricts urine flow.

Urogynecology

- Incontinence Assessment: For women suffering from urinary leakage, cystoscopy can rule out anatomical defects, fistulas (abnormal connections between the bladder and vagina), or foreign bodies (like eroded surgical mesh) contributing to the problem.

The Patient Experience of Cystoscope

A diagnostic cystoscopy is a quick procedure, typically taking only 5 to 10 minutes.

Preparation

There is usually no need for fasting or bowel preparation. The patient is asked to empty their bladder immediately before the test to provide a fresh urine sample (to rule out active infection) and to measure how effectively they void. The patient then lies on an exam table with feet placed in stirrups.

The Procedure

- Anesthetic Gel: The crucial step for comfort is the application of a lidocaine-based numbing jelly into the urethra. This is left for a few minutes to desensitize the area.

- Insertion: The doctor gently inserts the tip of the scope.

- Sensation: As the scope passes through the sphincter (the muscle that controls urine release), the patient may feel a momentary “pinch” or pressure, similar to the urge to urinate.

- Filling: As saline water fills the bladder, the sensation of needing to urinate will become stronger and the water might feel cool. This is normal; the bladder must be full to be examined properly.

- Visualization: The patient can often watch the monitor with the doctor, seeing the inside of their own bladder in real-time. The doctor will point out the ureteral orifices (where urine enters from the kidneys) and the bladder dome.

Post-Procedure

Once the scope is removed, the patient can use the restroom to empty the saline.

- Temporary Symptoms: It is normal to feel a slight burning sensation during the first urination after the test. You may also see a tinge of pink in the urine due to minor irritation. These symptoms typically resolve within 24 hours. Drinking plenty of water helps flush the system and soothe the area.

Safety and Precision Standards

Cystoscopy is a low-risk procedure, but strict protocols are maintained to ensure safety and diagnostic accuracy.

Sterilization and Infection Control

The risk of introducing a urinary tract infection (UTI) is the primary concern.

- High-Level Disinfection: Reusable scopes undergo a rigorous automated chemical sterilization process between every patient. This kills all bacteria, viruses, and spores.

- Single-Use Options: In some settings, disposable single-use flexible cystoscopes are utilized. These eliminate cross-contamination risks entirely and ensure that the optics are brand new and pristine for every single exam.

Trauma Prevention

The design of modern flexible scopes includes a tapered, atraumatic tip (often called a “beak” tip) designed to slide through the urethra without scraping the delicate lining. Physicians are trained to never use force; the flow of water acts as a “hydro-dilator,” opening the path ahead of the scope so the instrument travels through a water tunnel rather than rubbing against tissue.

Digital Enhancement (NBI)

To minimize human error in missing flat tumors, many systems use Narrow Band Imaging (NBI). By filtering out red light, this technology enhances the visibility of blood vessels. Since tumors are highly vascular (blood-rich), they appear dark green or brown against the normal background, acting as a visual alarm that prompts the urologist to take a biopsy of an area that might look normal under standard white light.