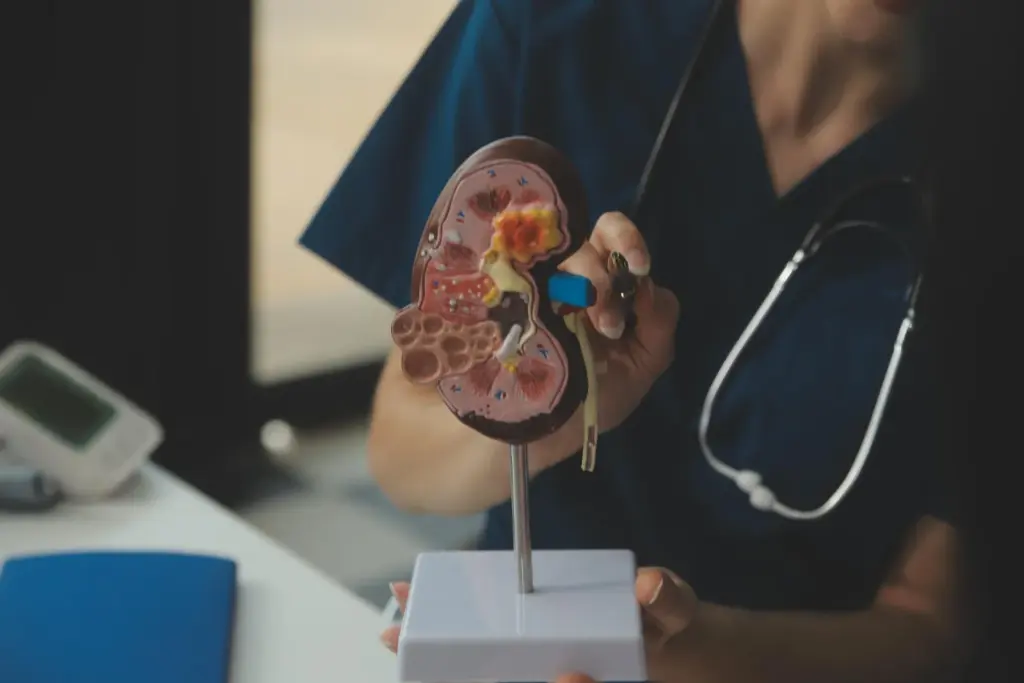

Kidney dialysis is a life-sustaining medical procedure that replicates the essential filtration functions of healthy kidneys. When kidneys fail, they can no longer remove waste products, excess fluids, and toxins from the blood. Dialysis steps in as an artificial replacement system, cleaning the blood mechanically to maintain the body’s chemical balance. It is not a cure for kidney disease but a critical maintenance therapy that keeps patients alive until kidney function recovers or a transplant becomes available.

The primary purpose of dialysis is to prevent the fatal accumulation of uremic toxins. Without this filtration, waste products like urea and creatinine build up in the bloodstream, leading to uremia a condition that poisons the body’s tissues. Additionally, dialysis manages fluid volume. Failed kidneys cannot produce urine, causing dangerous fluid retention that can flood the lungs (pulmonary edema) and strain the heart. Dialysis removes this excess water, regulating blood pressure and maintaining the precise balance of electrolytes like potassium and sodium that are vital for heart and muscle function.

How the Kidney Dialysis Works?

Dialysis works through the principles of diffusion and ultrafiltration across a semipermeable membrane. There are two main types: Hemodialysis (filtering blood outside the body) and Peritoneal Dialysis (filtering inside the body). Hemodialysis is the most common form in clinical settings.

The Dialyzer (Artificial Kidney)

The core component of hemodialysis is the dialyzer. It is a plastic cylinder containing thousands of hollow, hair-thin fibers.

- Blood Compartment: Blood flows through the inside of these hollow fibers.

- Dialysate Compartment: A specialized cleaning fluid called “dialysate” flows around the outside of these fibers.

- The Membrane: The walls of the fibers act as a semipermeable membrane. They have microscopic pores large enough to let small waste molecules (urea, potassium) pass through but small enough to keep vital blood cells and proteins inside.

Diffusion and Concentration Gradients

Cleaning occurs via diffusion.

- Waste Removal: The blood has high concentrations of waste. The dialysate has zero waste. Nature seeks balance, so the waste molecules naturally move from the area of high concentration (blood) through the membrane pores into the area of low concentration (dialysate).

- Electrolyte Balancing: The dialysate contains precise levels of minerals like calcium and bicarbonate. If the patient’s blood is low in these, they diffuse from the dialysate into the blood, restoring healthy levels.

Ultrafiltration (Fluid Removal)

To remove excess water, the machine applies pressure.

- Pressure Gradient: The machine creates a negative pressure (suction) on the dialysate side of the membrane. This pulls excess water from the blood, across the membrane, and into the waste fluid, simulating the water-removing action of healthy kidneys.

Clinical Advantages and Patient Benefits

Modern dialysis technology offers significant improvements over earlier generations, focusing on physiological stability and long-term health preservation.

Enhanced Toxin Clearance (High-Flux Membranes)

Modern “high-flux” dialyzers use membranes with larger pores and better biocompatibility.

- Middle Molecule Removal: Older membranes only removed small toxins like urea. High-flux membranes can remove larger “middle molecules” (like beta-2 microglobulin) that cause long-term complications like amyloidosis (joint pain and stiffness).

- Biocompatibility: Newer synthetic membranes trigger less immune system reaction than older cellulose-based ones, reducing chronic inflammation and improving overall nutritional status.

Precision Fluid Management

Fluid overload is a major cardiac risk. Modern machines use “Volumetric Control.”

- Exact Removal: The machine can be programmed to remove a specific volume of fluid (e.g., exactly 2.5 liters) over the course of the treatment.

- Profiling: Advanced machines can vary the rate of fluid removal. They might remove more fluid at the beginning when the patient is stable and less at the end to prevent cramping and blood pressure drops.

Hemodiafiltration (HDF)

This is an advanced form of dialysis that combines diffusion with “convection” (washing the blood with large volumes of fluid).

- Superior Cleaning: It literally pushes fluid through the membrane to drag toxins out, rather than just waiting for them to diffuse. Studies suggest HDF offers better cardiovascular protection and improved survival rates compared to standard hemodialysis.

Targeted Medical Fields and Applications

Dialysis is the central pillar of Nephrology, but its application is critical across acute care and chronic disease management.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

- End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD): This is the permanent loss of kidney function (Stage 5 CKD). Dialysis serves as lifetime replacement therapy for these patients unless they receive a transplant.

- Bridge to Transplant: It keeps the patient healthy and strong enough to withstand eventual transplant surgery.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

- Critical Care (ICU): Sudden kidney failure can occur due to severe infection (sepsis), trauma, or major surgery. In these cases, dialysis is often temporary. It supports the body for a few weeks until the kidneys heal and regain function.

- Toxin Overdose: Dialysis is used in emergency medicine to rapidly filter certain poisons (like ethylene glycol or lithium) from the blood that the kidneys cannot clear fast enough.

Cardiology (Cardio-Renal Syndrome)

- Heart Failure: Patients with severe heart failure often have fluid overload that diuretics (water pills) cannot fix. “Ultrafiltration” (a simplified form of dialysis) mechanically removes this fluid to relieve strain on the heart and lungs.

Step-by-Step: The Kidney Dialysis Experience

A typical in-center hemodialysis schedule involves treatments three times a week, with each session lasting roughly 4 hours.

Vascular Access Preparation

Before treatment can start, a reliable entry point to the bloodstream is needed.

- AV Fistula: A surgeon creates a connection between an artery and a vein in the arm. This strengthens the vein, allowing it to handle the high blood flow required for the machine. This is the “gold standard” access.

- Needle Insertion: At the start of every session, two needles are inserted into the fistula. One draws blood out to the machine; the other returns cleaned blood to the body. Numbing cream is often used to minimize the pinch.

The Treatment Session

- Connection: The patient sits in a specialized recliner. The tubing is connected, and the blood pump starts. Patients can see their blood flowing through the clear tubes into the dialyzer.

- During the Run: The process is painless. Patients can sleep, read, watch TV, or use Wi-Fi. Blood pressure is checked frequently (every 30 minutes) to ensure stability.

- Alarms: The machine may beep occasionally. This is normal; it signals the nurse to adjust a pressure setting or check a tube.

Post-Treatment

- Disconnection: The needles are removed, and pressure is applied to the sites to stop bleeding (usually 5-10 minutes).

- Recovery: Patients may feel “washed out” or tired immediately after treatment due to the fluid shift. This “post-dialysis fatigue” typically improves after a few hours of rest and a meal.

Safety and Precision Standards

Dialysis safety is governed by rigorous technical and procedural protocols to protect patients from infection and hemodynamic instability.

Water Purity Standards

The dialysate fluid is made by mixing concentrate with water. Since this water comes into contact with the patient’s blood (across the membrane), it must be ultrapure.

- Reverse Osmosis (RO): Dialysis centers have massive, industrial-grade water treatment plants. They use Reverse Osmosis, carbon filtration, and UV light to remove all bacteria, viruses, chlorine, and endotoxins (bacterial fragments) from the water.

- Endotoxin Testing: The water is tested daily to ensure it meets strict purity standards, preventing pyrogenic reactions (fever/chills) in patients.

Real-Time Safety Monitoring

The dialysis machine is a sophisticated safety monitor.

- Air Detectors: An ultrasonic sensor on the return line detects microscopic air bubbles. If even a tiny bubble is found, a clamp instantly snaps shut to stop the blood flow, preventing an air embolism from reaching the patient.

- Blood Leak Detector: An optical sensor watches the waste fluid. If the membrane inside the dialyzer breaks, blood cells would leak into the waste. The sensor detects the color change (red) and stops the pump immediately to prevent blood loss.

- Conductivity Monitoring: The machine constantly measures the electrolyte mix of the dialysate. If the sodium or potassium levels drift even slightly off target, the fluid bypasses the dialyzer to prevent chemical imbalance in the patient.

test