A newborn’s skeleton contains 90 more bones than an adult’s—a surprising fact that shapes how we count the body’s structural connections. This natural fusion process complicates precise joint calculations, creating a medical mystery hiding in plain sight. Learn how many joints are in the human body and how they support movement and flexibility.

We understand the challenge of determining exact figures for anatomical structures. Medical definitions vary widely: some experts count every bone intersection, while others focus only on movable connections. Sesamoid bones, like those in the kneecap, further blur the lines between tendons and skeletal components.

Age plays a critical role in these calculations. As children grow, cartilage transforms into solid bone, reducing total counts by nearly 25%. These developmental changes mean joint numbers fluctuate throughout life, making standardized measurements difficult.

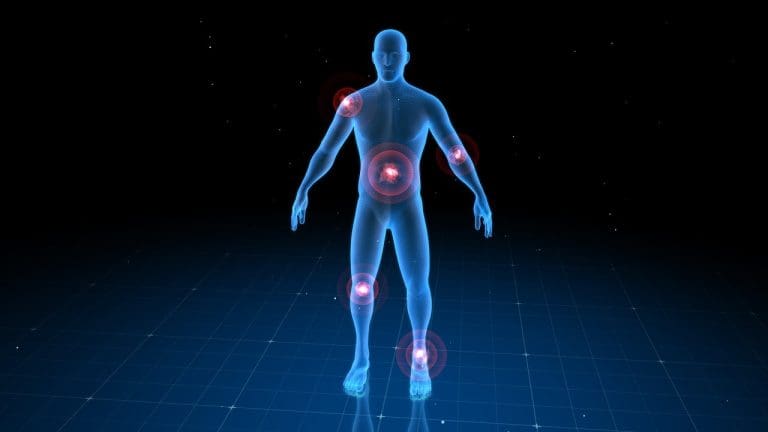

The human skeleton’s adaptability adds another layer of complexity. Joints evolve to support movement patterns, heal after injuries, and compensate for wear. This dynamic nature explains why estimates range from 250 to 350 connections—a spectrum reflecting both biological diversity and diagnostic interpretation.

Key Takeaways

- Joint counts depend on medical definitions and diagnostic criteria

- Sesamoid bones create classification challenges in anatomical studies

- Bone fusion during growth reduces total counts by adulthood

- Movable vs. immovable connections affect categorization

- Estimates account for natural variations between individuals

Understanding the Human Skeletal System

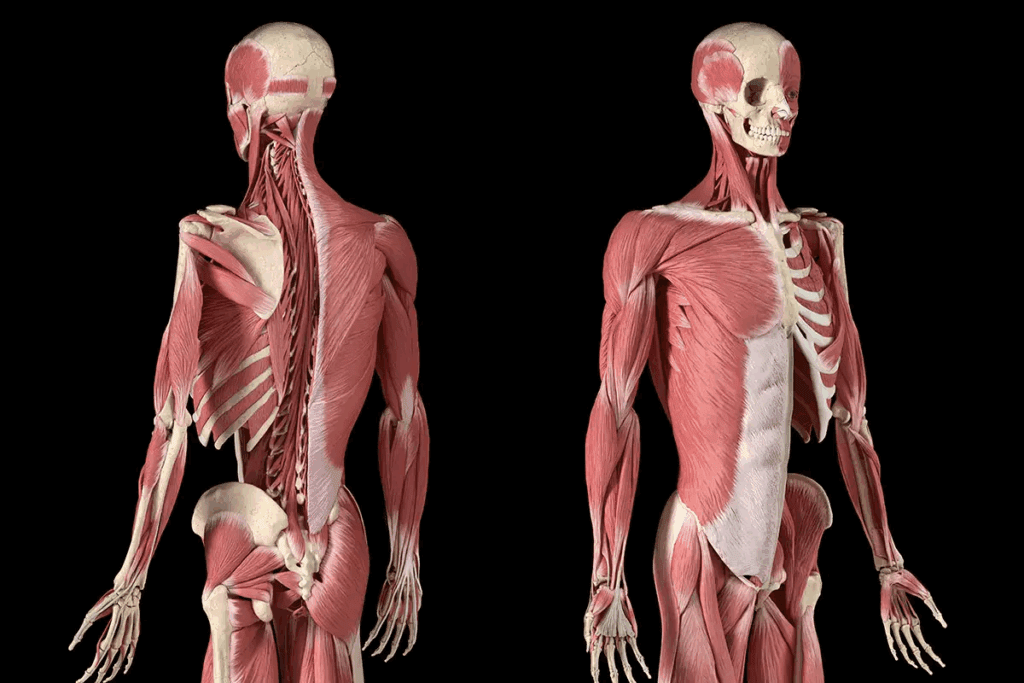

The body’s architectural marvel reveals its genius through gradual refinement. Newborns begin with 270 flexible structures designed for rapid growth. By adulthood, strategic fusion creates 206 durable elements optimized for strength and mobility.

The Number of Bones and Their Fusion Over Time

Ossification transforms soft cartilage into hardened tissue over two decades. Separate components like the skull’s frontal plates merge seamlessly. This natural engineering reduces bone counts by 24%, prioritizing structural integrity over quantity.

| Skeleton Division | Adult Count | Primary Role |

| Axial | 80 | Protects brain, heart, and spinal cord |

| Appendicular | 126 | Enables limb movement and manipulation |

| Total | 206 | Balances protection with mobility |

Connections Between Bones and Articulations

Three primary connective tissues form the skeleton’s functional network. Cartilage cushions impact zones like rib junctions. Tendons translate muscle force into motion at limb connections.

Ligaments provide crucial stability for load-bearing areas. This triad enables both fixed unions and mobile joints, adapting to each anatomical need. Precision in these connections explains why skeletal flexibility varies between individuals.

Exploring How Many Joints are in the Human Body

Medical professionals face unique challenges when quantifying skeletal connections. Standard estimates range from 250 to 350 structural links, reflecting anatomical complexity. This variance stems from differing definitions of what constitutes a functional connection between bones.

Sesamoid structures significantly impact final tallies. These tendon-embedded components, like the kneecap, exist outside traditional bone-to-bone classifications. Some experts count them, while others exclude these mobile elements from joint calculations.

| Factor | Impact on Count | Example |

| Sesamoid Inclusion | ±15-25 | Patella classification debates |

| Age Differences | 20% reduction | Fused childhood bones |

| Diagnostic Criteria | ±50 | Fixed vs. mobile distinctions |

Individual biological variations further complicate precise measurements. Extra sesamoid formations appear in 10-30% of adults, particularly in hands and feet. These developmental differences create personalized skeletal architectures.

Movement capabilities influence categorization methods. Connections enabling gliding or rotational motion receive priority in functional assessments. Medical teams prioritize this approach when evaluating mobility issues or treatment plans.

Our understanding evolves as imaging technologies advance. Recent studies reveal previously undetected micro-connections in spinal structures. These discoveries continue reshaping anatomical reference materials worldwide.

Diverse Types of Joints and Their Movements

Movement defines life – and our skeletal connections prove this truth through specialized designs. We categorize these biological hinges into three functional groups, each engineered for specific physical demands.

Synarthroses: Nature’s Immovable Fasteners

Fibrous joints create permanent bonds between bones. Skull sutures demonstrate this rigid fusion, forming protective armor for the brain. “These fixed connections act as the body’s architectural glue,” notes a leading orthopedic researcher.

Amphiarthroses: The Flexible Compromisers

Cartilaginous joints allow subtle shifts while maintaining stability. Spinal discs between vertebrae absorb shocks during walking. This limited movement prevents damage while enabling essential bending motions.

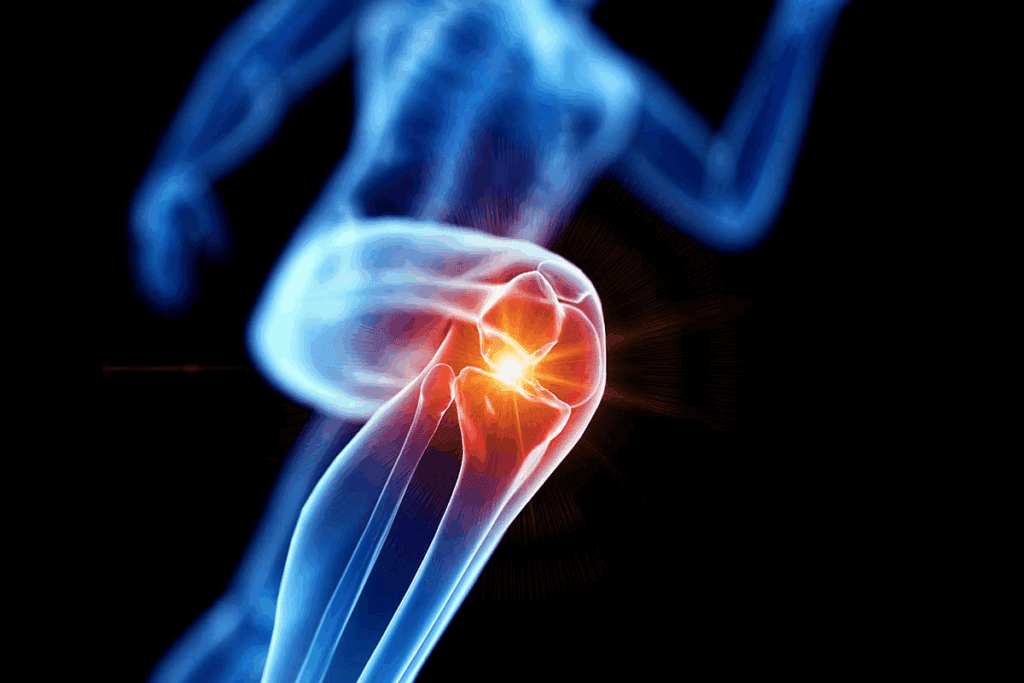

Diarthroses: Masters of Motion

Synovial joints dominate movement with six distinct subtypes:

- Ball-and-socket (shoulder/hip): 360° rotation

- Hinge (elbow/knee): Door-like flexion

- Saddle (thumb base): Precise grip adjustments

| Joint Type | Movement Range | Key Example |

| Pivot | Rotational | Neck vertebrae |

| Gliding | Sliding | Wrist bones |

| Condyloid | Multiplanar | Finger bases |

Each design combines synovial fluid lubrication with specialized surfaces. This biological engineering allows everything from delicate finger movements to powerful leg thrusts.

Conclusion

Human anatomy reveals its sophistication through skeletal connections. While estimates suggest 250-350 joints exist, precise counts remain elusive. Classification debates and biological variations create this range, emphasizing function over numbers.

Three primary types govern our mobility. Immovable synarthroses secure critical structures like skull plates. Slightly mobile amphiarthroses cushion spinal movements. Freely movable diarthroses enable complex actions through synovial fluid mechanics.

Understanding these distinctions directly impacts health outcomes. Recognizing joint roles helps address pain sources and preserve mobility. Individual bone fusion patterns mean each body develops unique anatomical solutions.

We prioritize this knowledge to empower proactive care. Regular movement maintains joint lubrication, while balanced nutrition supports bone density. Medical teams use these principles to create personalized treatment plans.

Our skeletal framework demonstrates nature’s adaptive genius. By valuing its complexity, we make informed choices that honor the body’s remarkable design.

FAQ

What are the three main categories of joints in the human skeleton?

The body contains synarthroses (immovable, like skull sutures), amphiarthroses (slightly movable, such as intervertebral discs), and diarthroses (freely movable, including ball-and-socket joints like the shoulder). Each type supports specific functions, from protection to dynamic motion.

How do bones and joints change as we age?

A> During growth, some bones fuse—like the sacrum—reducing their total count. Joints also adapt: cartilage may wear in synovial types, while fibrous or cartilaginous joints stabilize skeletal structures. Proper care maintains mobility and reduces age-related stiffness.

What’s the estimated count of movable joints in adults?

Most adults have approximately 350 joints, though this varies slightly. Freely movable synovial joints—such as knees, elbows, and hips—account for most functional movement, while fused or semi-mobile types provide structural integrity.

Why do synovial joints allow the widest range of motion?

These diarthrotic joints feature a lubricating synovial fluid, smooth cartilage surfaces, and a capsule. Subtypes like hinge (elbow) and pivot (neck) enable precise movements, while saddle joints (thumb) offer multi-directional flexibility.

Which joints are critical for rotational movements?

Pivot joints, like the proximal radioulnar joint in the forearm, permit rotation. The atlantoaxial joint in the neck allows head turning. These rely on bony grooves and ligaments to control motion safely.

How do cartilaginous joints differ from fibrous ones?

A> Cartilaginous joints, such as the pubic symphysis, use hyaline or fibrocartilage for shock absorption and limited movement. Fibrous joints, like skull sutures, connect bones via dense collagen, preventing movement entirely for protection.

Reference

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2024). Health lesson: Learning about joints. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/educational-resources/health-lesson-learning-about-joints NIAMS

Juneja, P. (2024). Anatomy, joints. In StatPearls. National Center for Biotechnology Information (U.S. National Library of Medicine). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507893/