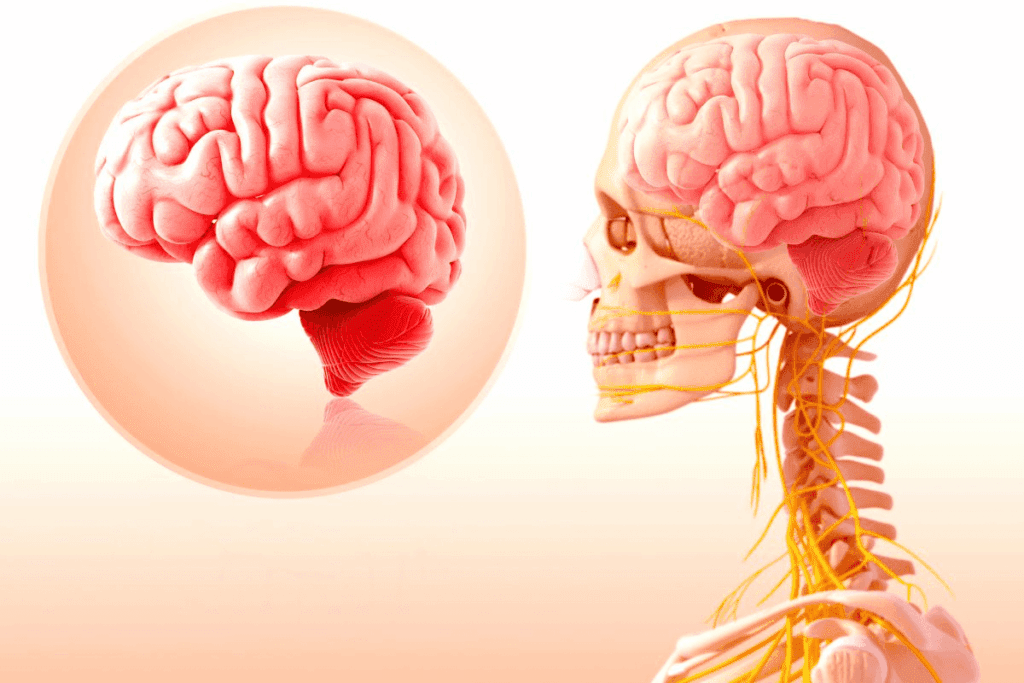

We know how key the cranial nerves are. They carry important info from the head and neck to the brain. The 12 cranial nerves start from the brain. The first two come from the cerebrum, and the other ten from the brainstem.inferior view of cranial nervesArteries of the Head: 7 Key Facts and Anatomy

The brainstem, made up of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, is where ten of the twelve cranial nerves begin. Knowing about the brainstem and cranial nerves helps us diagnose and treat brain issues. At Liv Hospital, we use this knowledge to give our patients the best care.

Key Takeaways

- The 12 cranial nerves play a vital role in controlling various bodily functions.

- The brainstem is the origin of ten of the twelve cranial nerves.

- Understanding cranial nerve anatomy is essential for neurological diagnosis and treatment.

- Cranial nerves transmit sensory and motor information throughout the head and neck.

- Liv Hospital’s patient-centered approach ensures complete care.

Overview of the Cranial Nerve System

The human brain is connected to the body through cranial nerves. These nerves are key for controlling how we feel and move. They start from the brain, unlike spinal nerves that come from the spinal cord.

Definition and Basic Anatomy

Cranial nerves are paired nerves that start from the brain. There are 12 pairs, labeled with Roman numerals (I-XII). Ten of these pairs come from the brainstem, showing its importance.

The brainstem, made up of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, is where most cranial nerves come from. Knowing about these nerves helps us understand their roles and why they matter.

Classification of Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves are divided into sensory, motor, or mixed types. Sensory nerves send information to the brain. Motor nerves control muscles. Mixed nerves do both.

- Sensory nerves (e.g., Olfactory nerve – CN I, Optic nerve – CN II)

- Motor nerves (e.g., Oculomotor nerve – CN III, Trochlear nerve – CN IV)

- Mixed nerves (e.g., Trigeminal nerve – CN V, Facial nerve – CN VII)

Clinical Significance

Cranial nerves are important for diagnosing and treating brain and nerve problems. Damage can cause symptoms like losing smell or vision. It can also affect speech and swallowing.

Healthcare professionals need to know about cranial nerves to find and treat problems in the nervous system.

Anatomy of the Brainstem and Cranial Nerve Origins

The brainstem, made up of the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, is key in cranial nerve anatomy. It is where ten of the twelve cranial nerves start. These nerves are vital for movement, sensation, and controlling body functions.

Midbrain Structure and Associated Nerves

The midbrain is at the top of the brainstem. It gives birth to two cranial nerves: the oculomotor nerve (CN III) and the trochlear nerve (CN IV). The oculomotor nerve helps with eye movements, pupil constriction, and keeping the eyelid open.

The trochlear nerve is the fourth cranial nerve. It controls the superior oblique muscle of the eye, which helps rotate the eyeball.

Pons Structure and Associated Nerves

The pons is below the midbrain. It houses nuclei for four cranial nerves: the trigeminal nerve (CN V), the abducens nerve (CN VI), the facial nerve (CN VII), and the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). The trigeminal nerve handles facial sensation and controls chewing.

The abducens nerve is in charge of the lateral rectus muscle, which moves the eye outward. The facial nerve controls facial expressions, taste from the tongue’s front two-thirds, and parasympathetic functions for salivary and lacrimal glands.

Medulla Oblongata Structure and Associated Nerves

The medulla oblongata is at the brainstem’s bottom. It is the birthplace of three cranial nerves: the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), the vagus nerve (CN X), and the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII). The glossopharyngeal nerve aids in swallowing, taste from the tongue’s back third, and salivation.

The vagus nerve has many parasympathetic roles, like controlling heart rate, gut movement, and secretion. The hypoglossal nerve controls tongue movements by innervating its muscles.

Forebrain Origins

Two cranial nerves, the olfactory nerve (CN I) and the optic nerve (CN II), come from the forebrain, not the brainstem. The olfactory nerve deals with smell, while the optic nerve handles vision.

Knowing where cranial nerves come from is key for diagnosing and treating neurological issues.

The Inferior View of Cranial Nerves: Anatomical Perspective

Looking at the brain from below shows the cranial nerves in order. This view is key for learning about their structure and how to check them during exams. From the bottom, the nerves come out of the brainstem in a specific order.

Rostral to Caudal Organization

The cranial nerves are arranged from top to bottom. This order is important for knowing their layout and roles. It helps doctors identify and check each nerve during exams.

Key aspects of this organization include:

- The first cranial nerve (Olfactory nerve) is located most rostrally.

- The subsequent nerves follow in numerical order caudally.

- This sequence is maintained as the nerves emerge from the brainstem.

Identifying Cranial Nerves from the Inferior Surface

To spot the cranial nerves from the bottom, you need to know their landmarks and order. You can find them by where they leave the brainstem and their position relative to other parts.

The steps to identify the cranial nerves include:

- Locate the olfactory bulbs and tracts for CN I.

- Identify the optic nerve (CN II) near the optic chiasm.

- Observe the oculomotor nerve (CN III) emerging between the cerebral peduncles.

- Continue this process for the remaining cranial nerves in their numerical order.

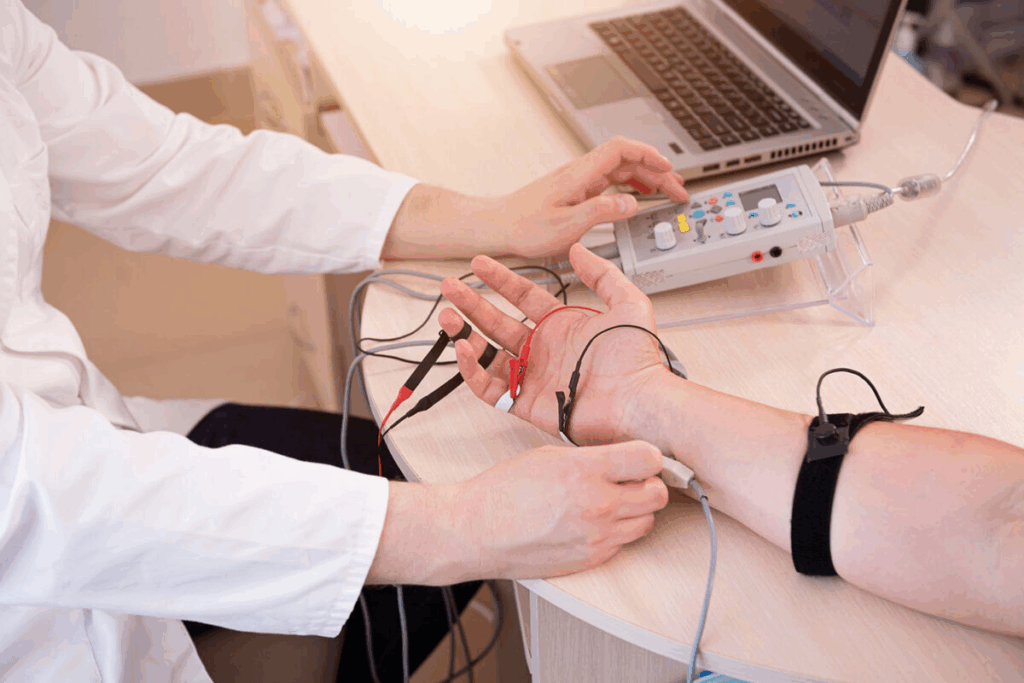

Clinical Examination Approach

When checking the cranial nerves, a methodical approach is needed. This means testing each nerve in a certain order, usually from top to bottom. This helps to fully check their functions.

Clinical examination tips:

- Start with the olfactory nerve (CN I) by testing the sense of smell.

- Proceed to examine the visual pathway through the optic nerve (CN II).

- Assess the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducens (CN VI) nerves for eye movements.

- Continue this systematic examination for all cranial nerves.

Olfactory Nerve (CN I): The Sense of Smell

The olfactory nerve, or CN I, is key for our sense of smell. It sends important sensory info from the nose to the brain. As the first cranial nerve, it helps us recognize different smells.

Origin and Pathway

The olfactory nerve starts in the nasal cavity’s olfactory epithelium. Specialized receptors in this area detect smells in the air we breathe. These receptors turn chemical signals into neural signals.

The nerve fibers from these receptors go through the cribriform plate to the olfactory bulb. The olfactory bulb is in the forebrain. It processes the smell info and sends it to other brain parts for understanding.

Function and Innervation

The main job of the olfactory nerve is to send smell info from the nose to the brain. This info helps us recognize and tell apart different smells. The nerve is exposed to the outside, making it prone to damage.

The nerve’s innervation is complex, involving many neural pathways. The olfactory receptors are connected to the nerve fibers. These fibers send the smell info to the olfactory bulb.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Testing the olfactory nerve checks how well a person can smell different odors. This is done with smell tests, where patients identify various smells.

Problems with the olfactory nerve can lead to anosmia, or losing the sense of smell. Anosmia can be caused by head injuries, infections, or diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Damage can also cause hyposmia, smelling less well, or dysosmia, smelling things differently.

Knowing how the olfactory nerve works is key for diagnosing and treating smell problems. Checking the olfactory nerve is a big part of neurological exams, mainly for those with suspected neurological issues.

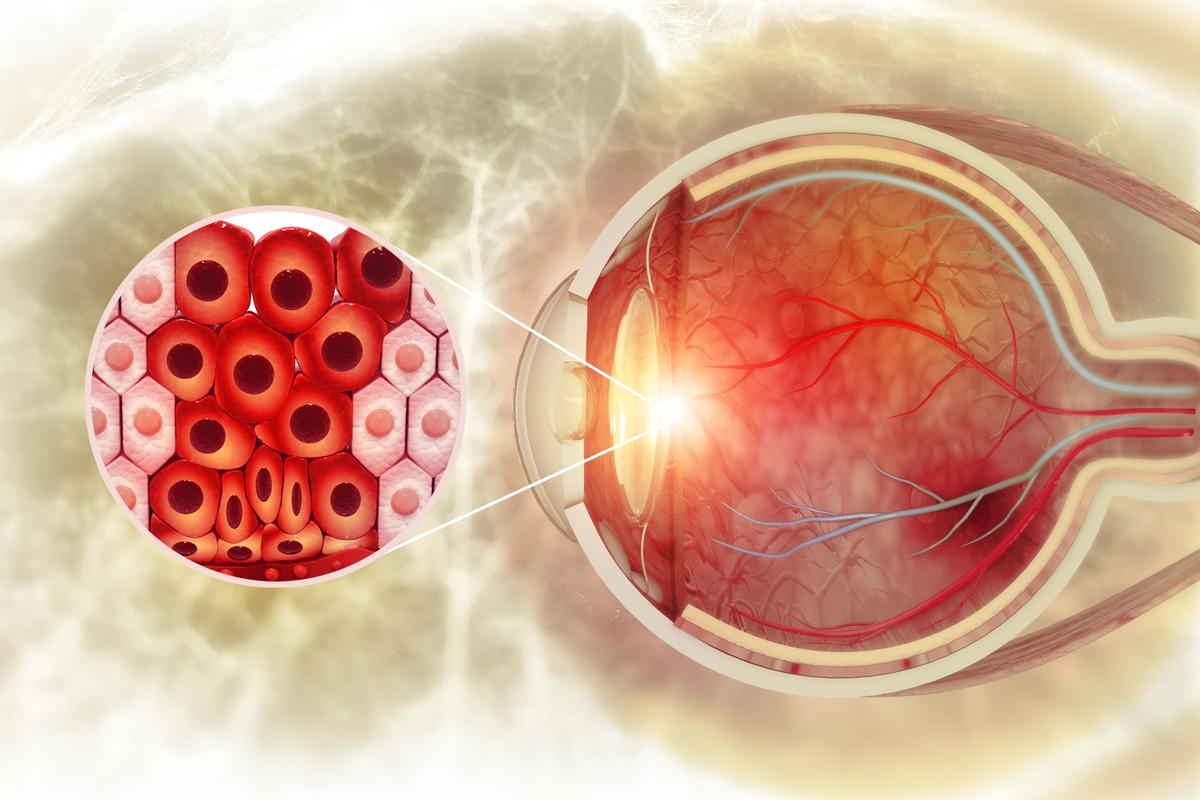

Optic Nerve (CN II): Visual Pathway

The optic nerve is key to our vision. It helps us see and understand what we look at. It carries visual information from the retina to the brain for processing.

Origin and Pathway

The optic nerve starts in the retina’s ganglion cells. These cells send signals through their axons to the optic disc. There, they form the optic nerve.

The optic nerve then goes through the optic canal and reaches the optic chiasm. Here, nerves from each eye cross over. This allows us to see with both eyes together.

After the optic chiasm, the optic tract goes to the thalamus. Then, it sends visual info to the primary visual cortex for processing.

Function and Innervation

The optic nerve’s main job is to send visual info. It carries details about light, color, and patterns from the retina to the brain. It’s not a true nerve but a part of the central nervous system.

The optic nerve combines signals from both eyes. This is important for seeing in depth and understanding the world around us.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Doctors test the optic nerve by checking visual acuity, fields, and the pupillary light reflex. Problems with the optic nerve can cause vision loss, blind spots, and color vision issues.

Optic neuritis and optic neuropathy are common issues. They can be caused by inflammation, compression, or toxicity. Knowing how the optic nerve works helps doctors diagnose and treat these problems.

Oculomotor Nerve (CN III): Eye Movement and Pupillary Control

The oculomotor nerve, or CN III, is key in controlling eye movements and how pupils constrict. It comes from the midbrain. This nerve is one of the 12 cranial nerves that help with many bodily functions, like eye movement and coordination.

Midbrain Origin and Pathway

The oculomotor nerve starts in the midbrain. This part of the brainstem has many nuclei for different cranial nerves. CN III comes from the oculomotor nucleus in the midbrain.

It goes through the interpeduncular fossa. Then, it passes between two arteries and enters the cavernous sinus. It reaches the orbit through the superior orbital fissure.

This journey is vital for the nerve’s function. Damage along the way can cause big problems.

Motor and Parasympathetic Functions

The oculomotor nerve has motor and parasympathetic functions. Its motor fibers control several eye muscles. These muscles help with eye movements.

The parasympathetic fibers help with pupillary constriction and lens accommodation for near vision.

- Motor Functions: Controls most of the eye’s movements.

- Parasympathetic Functions: Regulates pupillary constriction and lens accommodation.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Testing the oculomotor nerve checks eye movements, pupillary reactions, and eyelid position. A full exam can show signs of nerve palsy. This might include a drooping eyelid, double vision, and a dilated pupil.

Disorders of CN III can come from many causes. These include vascular issues, trauma, tumors, and aneurysms. Knowing how nerve problems affect the oculomotor nerve is key for diagnosis and treatment.

Understanding the oculomotor nerve’s role in the brain is important. It shows how complex and interconnected our nervous system is.

Trochlear Nerve (CN IV): Superior Oblique Muscle Control

The trochlear nerve starts in the midbrain and is the thinnest cranial nerve. It’s key for eye movement. We’ll look at its special traits, roles, and why it matters in health.

Midbrain Origin and Unique Pathway

The trochlear nerve comes from the trochlear nucleus in the midbrain. It’s different because it exits the brainstem from the back. It also crosses over before reaching the superior oblique muscle. This special path is vital for its role in eye movement.

Function and Innervation

The trochlear nerve controls the superior oblique muscle. This muscle helps rotate the eyeball. It’s mainly for moving the eye down when it’s pulled in.

Key Functions of the Superior Oblique Muscle:

- Intorsion (rotating the top of the eyeball toward the nose)

- Depression (moving the eyeball downward)

- Abduction (when the eye is adducted)

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Testing the trochlear nerve checks the superior oblique muscle’s work. It looks for signs of weakness or paralysis, like double vision. Problems with the trochlear nerve can come from injuries, lack of blood, or other issues in the midbrain or nerve.

Clinical Presentation: People with trochlear nerve palsy might have double vision, tilt their head, and struggle with looking down.

Knowing about the trochlear nerve’s structure and function is key for diagnosing and treating related problems. As health workers, we need to understand its clinical importance to give the right care.

Trigeminal Nerve (CN V): Sensation and Mastication

The trigeminal nerve starts in the pons and is key for face sensation and chewing. It’s the biggest cranial nerve. It helps us feel sensations from our face and chew food.

Pontine Origin and Three Divisions

The trigeminal nerve comes from the pons in the brainstem. It splits into three parts: ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. Each part does different things.

The ophthalmic part handles the eye and nearby areas. The maxillary part covers the mid-face and teeth. The mandibular part does both sensing and moving, like chewing.

Sensory and Motor Functions

The trigeminal nerve mainly deals with feeling sensations like pain and touch on the face. It also controls the muscles for chewing.

Its sensing abilities help us feel the face. Its motor functions let us chew and grind food.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Doctors test the trigeminal nerve to see how it works. They check if we can feel touch and pain on the face. They also look at how well we chew.

Problems with the trigeminal nerve can cause pain or trouble chewing. Knowing how to test and treat these issues is important.

Abducens Nerve (CN VI): Lateral Rectus Control

The abducens nerve starts in the pons and controls the lateral rectus muscle. It is one of twelve cranial nerves that help move our eyes.

Pontine Origin and Pathway

The abducens nerve comes from the pons, a brainstem part. Its nucleus is in the pons. It goes up through the cavernous sinus and into the orbit through the superior orbital fissure to reach the lateral rectus muscle.

Function and Innervation

The abducens nerve mainly controls the lateral rectus muscle. This muscle helps us move our eyes outward. It’s key for eye movement to the side.

This nerve is a motor nerve. It sends signals from the brain to the muscle. This tells the muscle to contract and move the eye outward. Damage can cause weakness or paralysis of the lateral rectus muscle, making it hard to move the eye.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Testing the abducens nerve checks if the patient can move their eyes laterally. A simple test is to ask the patient to look sideways. If the nerve is damaged, the patient might struggle to move the eye outward.

Clinical Test | Normal Response | Abnormal Response |

Looking sideways | Eye moves outward | Eye fails to move outward or moves partially |

Cover-uncover test | No deviation detected | Esotropia (inward deviation) observed |

Disorders of the abducens nerve can come from trauma, vascular issues, or tumors. Treatment varies based on the cause. It might include addressing the cause, physical therapy, or other methods to manage symptoms.

Facial Nerve (CN VII): Facial Expression and Taste

The facial nerve (CN VII) starts in the pons and is key for facial expressions and taste. It controls the muscles of the face and sends taste info from the tongue’s front parts. This nerve is vital for both voluntary and involuntary facial movements and taste sensation.

Pontine Origin and Complex Pathway

The facial nerve begins in the pons, a brainstem part. It has a complex path with both motor and sensory roles. It goes through the pontine nuclei, the internal auditory meatus, and exits through the stylomastoid foramen. This detailed path is essential for its many functions.

Motor, Sensory, and Parasympathetic Functions

The facial nerve performs several important tasks:

- It controls the muscles of facial expression.

- It sends taste info from the tongue’s front parts.

- It also innervates glands like the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

These roles show the nerve’s importance in both voluntary actions, like smiling, and involuntary actions, like tearing.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Clinical tests check facial symmetry, muscle strength, and taste on the tongue’s front. Disorders like facial paralysis or weakness can affect the nerve. They can also disrupt taste sensation.

Knowing the facial nerve’s functions and path is key for diagnosing and treating nerve issues. It ensures proper care for those with related problems.

Vestibulocochlear Nerve (CN VIII): Balance and Hearing

The vestibulocochlear nerve starts in the pons and is key for balance and hearing. Known as CN VIII, it helps us stay balanced and hear sounds.

Pontine Origin and Dual Components

The vestibulocochlear nerve comes from the pons in the brainstem. It has two parts: the vestibular and cochlear nerves. The vestibular nerve helps with balance, and the cochlear nerve is for hearing.

Together, these parts help us understand our surroundings. The vestibulocochlear nerve is all about sensing, not moving.

Vestibular and Cochlear Functions

The vestibular part of CN VIII is vital for balance. It notices changes in head position and movement. This helps us stay upright and move around.

The cochlear part is for hearing. It sends sound info from the inner ear to the brain. There, it’s turned into sound we can understand.

Component | Function | Related Sensation |

Vestibular Nerve | Balance and Equilibrium | Spatial Orientation |

Cochlear Nerve | Hearing | Sound Perception |

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Doctors test the vestibulocochlear nerve to check its balance and hearing parts. These tests help see if the nerve is working right.

Problems with CN VIII can cause vertigo, dizziness, and hearing loss. Knowing about CN VIII helps doctors find and treat these issues.

We’ve looked at where the vestibulocochlear nerve comes from, its parts, and what it does. It’s very important for our everyday life. Doctors use this knowledge to help with related health problems.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX): Throat and Taste

The glossopharyngeal nerve is a complex cranial nerve. It comes from the medulla oblongata and is involved in many processes. It helps transmit sensory information from the throat, controls swallowing, and provides taste from the tongue’s back third.

Medullary Origin and Pathway

The glossopharyngeal nerve starts in the medulla oblongata, a key part of the brainstem. Its fibers come out between the olive and the inferior cerebellar peduncle. Then, they go laterally and exit the skull through the jugular foramen.

After leaving the skull, the nerve goes down between the internal jugular vein and the internal carotid artery. It eventually reaches its target structures.

Sensory, Motor, and Parasympathetic Functions

The glossopharyngeal nerve has many functions:

- Sensory innervation to the posterior third of the tongue and the pharynx, contributing to the sensation of taste and general visceral sensation.

- Motor innervation to the stylopharyngeus muscle, which aids in swallowing.

- Parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland, regulating salivary secretion.

These diverse functions show the nerve’s importance in both voluntary and involuntary processes, like swallowing and salivation.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Clinical assessment of the glossopharyngeal nerve involves checking its functions. This includes taste sensation from the tongue’s back third and the gag reflex. Disorders can cause swallowing problems, taste loss, and other issues.

Some common conditions that may affect the glossopharyngeal nerve include:

- Trauma to the neck or skull base.

- Infections such as Lyme disease or viral neuritis.

- Neurological conditions like multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Understanding the glossopharyngeal nerve’s functions and disorders is key for diagnosing and managing related clinical conditions effectively.

Vagus Nerve (CN X): Visceral Innervation

The vagus nerve starts in the medulla oblongata and is key to many body functions. Known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), it has many roles in the body.

Medullary Origin and Extensive Pathway

The vagus nerve begins in the medulla oblongata, a part of the brainstem. It travels from the brain to the abdomen, touching many organs. This nerve helps control the heart, lungs, and digestive system through parasympathetic innervation.

Parasympathetic, Motor, and Sensory Functions

The vagus nerve does several things:

- Parasympathetic Functions: It helps control heart rate, aids digestion, and manages other involuntary actions.

- Motor Functions: It controls muscles for swallowing and speaking.

- Sensory Functions: It sends information from organs to the brain.

This shows how important the vagus nerve is for our body’s functions.

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Doctors test the vagus nerve to see how it works. They check the gag reflex and heart rate. Problems with the vagus nerve can cause issues like:

- Gastroparesis, where the stomach muscles don’t work right.

- Vocal cord paralysis, which affects speaking and breathing.

- Heart rate problems because of nerve issues.

Knowing about the vagus nerve’s role and possible problems helps doctors diagnose and treat these issues.

For a full picture, looking at a cranial nerves summary or a table of cranial nerves is useful. These resources give a detailed look at all cranial nerves, including the vagus nerve, and what they do.

Accessory Nerve (CN XI): Neck Muscle Control

CN XI is key for many motor functions. It’s special because it comes from both the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord.

Medullary Origin and Spinal Components

The Accessory Nerve has two parts: the cranial root and the spinal root. The cranial root comes from the medulla oblongata. The spinal root comes from the upper cervical spinal cord.

Cranial Root: This root starts in the medulla oblongata. It joins the spinal root briefly before merging with the vagus nerve (CN X).

Spinal Root: This root comes from the upper cervical spinal cord (C1-C5/C6). It goes through the foramen magnum and exits the skull through the jugular foramen.

Motor Functions and Innervation

The Accessory Nerve mainly controls two muscles: the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius.

- The sternocleidomastoid muscle rotates the head and flexes the neck.

- The trapezius muscle elevates, depresses, and rotates the scapula.

Muscle | Function | Innervation |

Sternocleidomastoid | Rotates head, flexes neck | Accessory Nerve (CN XI) |

Trapezius | Elevates, depresses, rotates scapula | Accessory Nerve (CN XI) |

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Testing the Accessory Nerve checks the strength of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. Weakness in these muscles can mean CN XI damage.

Problems with CN XI can come from trauma, surgery, or neurological issues. Symptoms include a drooping shoulder, weak head rotation, or trouble lifting the arm.

Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII): Tongue Movement

The hypoglossal nerve, or CN XII, is key for tongue movements. It helps us speak and swallow. It mainly controls the tongue muscles.

Origin and Pathway

The hypoglossal nerve starts in the medulla oblongata, a brainstem part. It forms from rootlets between the pyramid and olive. Then, it exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal and goes down the neck to the tongue.

Key points about the hypoglossal nerve’s pathway:

- Originates from the medulla oblongata

- Exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal

- Descends through the neck to reach the tongue

Motor Functions and Innervation

The hypoglossal nerve controls all tongue muscles, except the palatoglossus. This muscle is controlled by the vagus nerve (CN X). It helps with speech, swallowing, and food manipulation.

The main functions include:

- Controlling tongue protrusion and retraction

- Facilitating tongue movements for speech articulation

- Assisting in the manipulation of food during mastication

Clinical Testing and Disorders

Clinical tests check tongue movements and strength. Patients are asked to stick out their tongue. If it deviates, it might show a nerve issue. Tongue weakness can make speech and swallowing hard.

Many things can harm the hypoglossal nerve, like trauma or tumors. Knowing how it works helps doctors diagnose and treat problems.

Let’s look at the hypoglossal nerve and other cranial nerves in a table:

Cranial Nerve | Function | Origin |

Hypoglossal (CN XII) | Tongue movement | Medulla oblongata |

Other cranial nerves | Varies (sensory, motor, mixed) | Brainstem and forebrain |

Conclusion: Integrating Cranial Nerve Knowledge in Clinical Practice

Knowing how the cranial nerves work is key for diagnosing and treating brain and nerve problems. These nerves control how we feel, move, and function on our own. So, studying them is vital for doctors and nurses.

It’s important to understand the cranial nerves on brainstem and how they connect. A cranial nerves map helps doctors see how these nerves work together. This makes diagnosing and treating easier.

Using cranial nerve innervation knowledge in practice helps doctors manage brain and nerve issues better. We stress the need for ongoing learning in this field to help patients more.

By getting the hang of cranial nerve details, doctors can give better diagnoses and treatment plans. This leads to better care for patients.

FAQ

What are the 12 cranial nerves and their functions?

The 12 cranial nerves control many functions. These include smell, vision, eye movements, facial expressions, and hearing. They also manage balance, swallowing, and tongue movements. The nerves are: Olfactory nerve (CN I), Optic nerve (CN II), Oculomotor nerve (CN III), Trochlear nerve (CN IV), Trigeminal nerve (CN V), Abducens nerve (CN VI), Facial nerve (CN VII), Vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII), Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), Vagus nerve (CN X), Accessory nerve (CN XI), and Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII).

Where do the cranial nerves originate from?

The cranial nerves start from the brainstem. The brainstem includes the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. Ten of the 12 cranial nerves come from here.

What is the clinical significance of understanding the cranial nerves?

Knowing about the cranial nerves is key for diagnosing and treating neurological issues. Damage to certain nerves can cause specific symptoms and problems.

How are the cranial nerves classified?

The cranial nerves are classified into sensory, motor, or mixed types. Sensory nerves send information, motor nerves control movements, and mixed nerves do both.

What is the inferior view of the brainstem and its significance?

The inferior view shows the cranial nerves as they leave the brainstem. It’s important for identifying and studying the nerves.

What is the role of the brainstem in cranial nerve function?

The brainstem is the starting point for ten of the 12 cranial nerves. It controls eye movements, facial expressions, swallowing, and tongue movements.

How are cranial nerves related to the skull?

The cranial nerves exit the brainstem and go through skull openings to reach their destinations. Knowing their paths is key to understanding their functions.

What is the significance of understanding the origins of the cranial nerves?

Knowing where the cranial nerves start is vital for understanding their roles and importance. Their origins are closely tied to their functions and the structures they serve.

How do the cranial nerves relate to the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata?

The cranial nerves start from specific parts of the brainstem, like the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. Each part is linked to certain nerves and functions.

What is the rostral to caudal organization of the cranial nerves?

The cranial nerves are arranged from top to bottom. This organization is important for identifying and examining them.

How are the cranial nerves tested clinically?

Clinicians test the cranial nerves using different methods. These include tests for sensory and motor functions to check their health.

What are some common disorders associated with cranial nerve damage?

Damage to certain nerves can lead to symptoms like anosmia (loss of smell), visual loss, and double vision. It can also cause facial weakness, hearing loss, and swallowing problems.

References

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Evidence-Based Medical Guidance. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544297/