The ability to enjoy our favorite foods’ flavors comes from a complex network of cranial nerves. Three nerves are key in sending taste information from the tongue and mouth. We’ll see how the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves work together to help us taste.which cranial nerve is responsible for smellWhich Is Best CT or MRI Scan?

Taste sensation is a complex process that involves these nerves. It shows how amazing our senses are. Knowing how these nerves work can also help us understand why taste problems can affect our health and nutrition.

Key Takeaways

- The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) is responsible for taste sensation in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- The glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) conveys taste information from the posterior third of the tongue.

- The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) plays a role in taste sensation from the epiglottis and other areas.

- Taste disturbance can significantly impact nutrition and wellbeing.

- The coordination of these three nerves enables our sense of taste.

The Neuroanatomy of Taste Perception

Taste perception is a complex sensory experience. It involves the work of many cranial nerves. This ability is key to our survival and quality of life, guiding our food choices and nutrition.

The journey of taste starts with taste receptors on the tongue and in the mouth. These receptors are tuned to five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

Basic Taste Sensations and Their Evolutionary Purpose

The five basic tastes help us judge food’s nutritional value and safety. Sweetness tells us about energy-rich foods. Bitterness warns of toxins. These abilities helped our ancestors survive and are important today.

- Sweetness indicates energy-rich foods.

- Sourness warns of acidity or spoilage.

- Saltiness is linked to essential minerals.

- Bitterness signals toxins.

- Umami taste is about protein-rich foods.

Overview of the Gustatory System

The gustatory system is a complex network of nerves. It sends taste information from the tongue and mouth to the brain. The cranial nerves involved in taste are the facial nerve (VII), glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and vagus nerve (X). Together, they ensure we get a full picture of taste.

The taste pathway includes several steps:

- Taste molecules bind to taste receptors on the tongue.

- Signals are sent to the cranial nerves.

- The cranial nerves send this info to the brainstem.

- The brain processes it, letting us experience different tastes.

Knowing about the taste pathway and the gustatory nerve helps us understand taste better. The complex processes show how vital the gustatory system is in our daily lives.

The Three Primary Taste Nerves

Three cranial nerves are key to our taste. They send taste signals from the tongue to the brain. This is a complex process involving many nerves.

Facial Nerve (Cranial Nerve VII)

The facial nerve sends taste signals from the front two-thirds of the tongue. It’s vital for tasting sweet, sour, salty, and bitter flavors. The chorda tympani branch of this nerve carries these taste fibers.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (Cranial Nerve IX)

The glossopharyngeal nerve handles taste for the back third of the tongue. It’s key for tasting in the tongue’s back part, adding to our taste experience.

Vagus Nerve (Cranial Nerve X)

The vagus nerve deals with taste in the epiglottis and throat areas. Though less talked about, it’s important for taste, helping with swallowing and throat sensations.

In short, the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves work together. They help us enjoy the tastes of food. Knowing their roles is key to understanding our taste system.

Facial Nerve (VII): Taste to the Anterior Tongue

The facial nerve carries taste information from the front part of the tongue to the brain. This is done through a special branch called the chorda tympani.

Anatomy and Course of the Facial Nerve

The facial nerve, or cranial nerve VII, has both motor and sensory fibers. It starts in the brainstem and goes out through the stylomastoid foramen. It then passes through the temporal bone, branching off into several nerves, including the chorda tympani.

The facial nerve’s anatomy is key to understanding its role in taste. While it’s known for controlling facial expressions, its sensory part handles taste.

The Chorda Tympani Branch

The chorda tympani is a branch of the facial nerve found in the temporal bone. It connects with the lingual nerve to reach the front part of the tongue.

The chorda tympani is specialized for taste sensation. It carries fibers for sweet, sour, salty, and bitter tastes from the tongue’s front part.

Taste Coverage Area and Sensations

The facial nerve, through the chorda tympani, handles taste in the tongue’s front part. It lets us detect:

- Sweet tastes

- Sour tastes

- Salty tastes

- Bitter tastes

This mix of tastes lets us enjoy a wide range of flavors. It’s vital for our food enjoyment and for detecting harmful substances.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (IX): Taste to the Posterior Tongue

The glossopharyngeal nerve is essential for tasting on the back part of the tongue. It’s a key part of our taste system, helping us enjoy different flavors.

Anatomical Pathway

The glossopharyngeal nerve, or cranial nerve IX, has a complex path. It starts in the brainstem, goes out through the jugular foramen, and then moves down. Along the way, it branches out.

Innervation of the Posterior Third of the Tongue

This nerve covers the back third of the tongue. It’s important for taste sensations in this area. Its branches, like the lingual branch, help with this.

Taste Sensations Mediated by CN IX

The glossopharyngeal nerve helps us feel sweet, sour, salty, and bitter tastes. This lets us enjoy all kinds of flavors on the back third of the tongue.

Taste Sensation | Description | Region of Tongue |

Sweet | Perception of sweetness | Posterior third |

Sour | Perception of acidity | Posterior third |

Salty | Perception of saltiness | Posterior third |

Bitter | Perception of bitterness | Posterior third |

Vagus Nerve (X): Taste in the Throat Region

The vagus nerve is key to our taste, mainly in the throat. It’s one of the cranial nerves that help us taste. This nerve, known as cranial nerve X, sends taste fibers to parts not covered by other nerves.

The Superior Laryngeal Branch

The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve is vital for throat taste. It connects to the epiglottis and nearby areas. This connection is important for the gag reflex and keeping the airway safe during swallowing.

Epiglottis and Pharyngeal Taste Sensation

The epiglottis, helped by the vagus nerve, is key for throat taste. It’s sensitive to chemicals and substances, helping to keep the airway safe. The pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve also help with taste in the pharynx, making our taste better.

Functional Significance of Vagal Taste Fibers

The taste fibers from the vagus nerve are important for airway protection. They help detect harmful substances and trigger responses like coughing or gagging. This is vital for preventing aspiration and keeping the respiratory tract safe.

Here’s a summary of the key aspects of the vagus nerve’s role in taste:

Aspect | Description |

Innervation Area | Epiglottis and pharynx |

Function | Taste sensation, gag reflex, airway protection |

Branch Involved | Superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve |

The Central Taste Pathway

The central processing of taste starts in the brainstem and goes to higher brain centers. This pathway is key for understanding taste. It begins with taste receptors on the tongue and in the mouth.

The Nucleus Solitarius (Gustatory Nucleus)

The nucleus solitarius, or gustatory nucleus, is in the medulla oblongata. It gets taste info from the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves. Then, it sends this info to other brain parts for processing.

Thalamic Relay: Ventral Posteromedial Nucleus

Taste info goes to the ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus next. This step is important for processing taste before it reaches the cortex.

Gustatory Cortex and Higher Processing

Then, taste info reaches the gustatory cortex. This is where we consciously experience taste. The gustatory cortex is in the insula and frontal operculum. It combines taste with smell and texture for flavor.

Structure | Function in Taste Pathway |

Nucleus Solitarius | Initial processing and convergence of taste information |

Ventral Posteromedial Nucleus | Thalamic relay for further processing of taste information |

Gustatory Cortex | Conscious perception of taste and integration with other sensory inputs |

Knowing the central taste pathway helps us understand how we taste and tell tastes apart. It’s a complex process. Many brain areas work together to turn chemical signals into the rich experience of flavor.

Which Cranial Nerve is Responsible for Smell vs. Taste

Knowing the difference between smell and taste helps us understand flavor better. Taste is handled by specific nerves, but smell is mainly controlled by another nerve.

The Olfactory Nerve (Cranial Nerve I)

The olfactory nerve, or Cranial Nerve I, carries smell information from the nose to the brain. In the nasal cavity, special receptors catch odor molecules. This starts a signal that the olfactory nerve sends to the brain.

This nerve can grow back throughout our lives. This is key for keeping our sense of smell. Damage to it can cause anosmia, or the loss of smell.

How Smell and Taste Interact

Smell and taste work together to create flavor. When we eat, smells from the food go up the throat and into the nose. Here, they meet the basic tastes on our tongue.

This mix of smells and tastes makes food taste rich and interesting. Without smell, food tastes dull and uninteresting.

Flavor Perception: The Combined Experience

Flavor is a mix of taste, smell, and other senses like texture and temperature. The cranial nerves responsible for taste (facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves) team up with the olfactory nerve. Together, they give us the varied and rich tastes we enjoy.

- Taste gives us basic tastes like sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

- Smell adds the complex and detailed flavors.

- Other senses like texture and temperature also add to flavor.

Learning about the roles of different nerves in smell and taste shows how complex our senses are. It also shows how important these senses are in our everyday lives.

Clinical Assessment of Taste Function

Testing taste function clinically is a detailed process. It involves different methods to diagnose and treat taste disorders. We aim to understand the causes and find the right treatment.

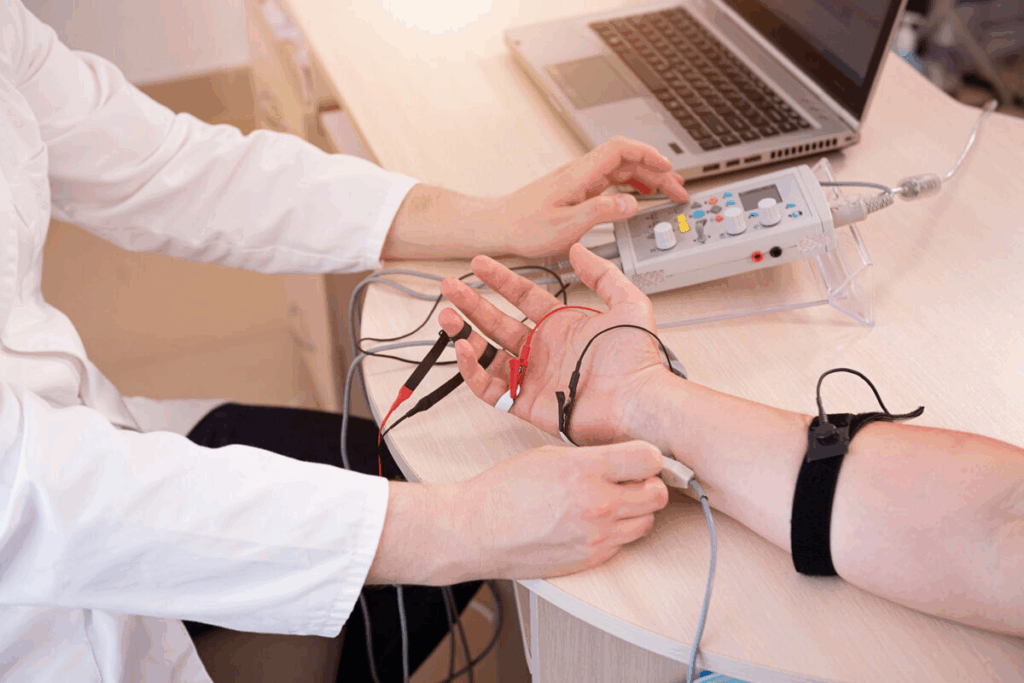

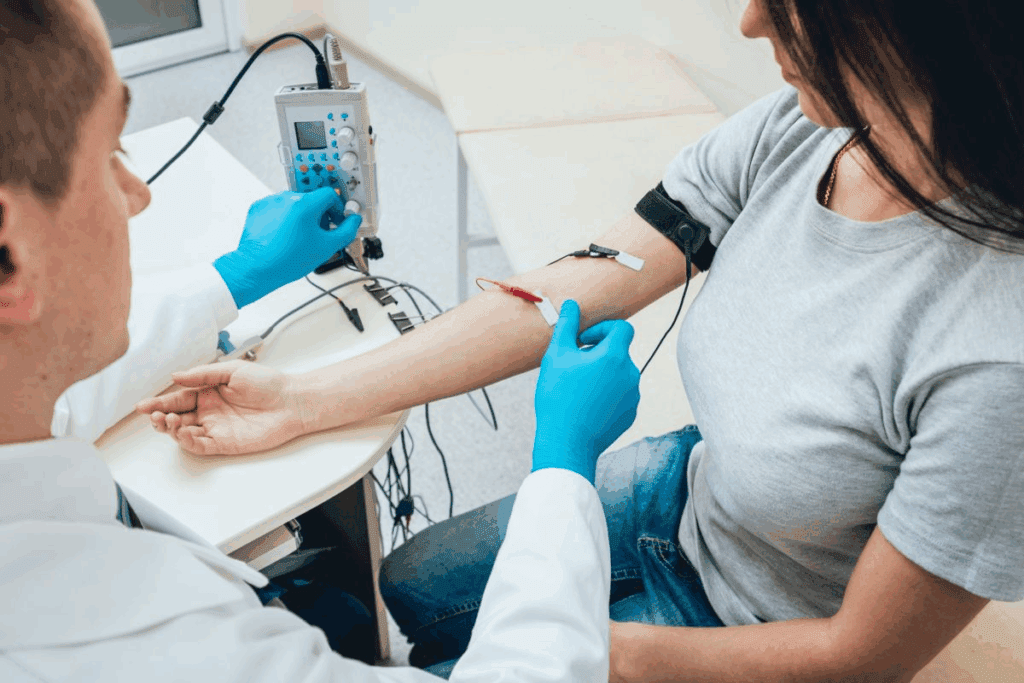

Electrogustometry and Taste Strips

Electrogustometry uses electrical stimulation to check taste. It finds out when a person can feel the stimulation on their tongue. Taste strips are also used. They have different tastes and are placed on the tongue to test taste in different areas.

Both methods give clear results about taste function. But, they have their limits. Electrogustometry might not work for everyone, and results can vary based on personal feelings.

Whole-Mouth Taste Testing

Whole-mouth taste testing uses various taste solutions to check overall taste. It shows how well a person can detect different tastes. This method tests taste in a natural way, covering the whole mouth.

This testing is simple and checks overall taste. But, it might miss small taste problems.

Regional Taste Testing Techniques

Regional taste testing focuses on specific tongue areas. It applies taste stimuli to see if there are problems. This method helps find out which nerves are involved in taste issues.

Some key techniques include:

- Taste strips on specific tongue areas

- Localized electrogustometry

- Regional taste solution application

By using these methods together, we get a full picture of a patient’s taste. This helps us create specific treatment plans.

Taste Disorders and Cranial Nerve Pathology

Cranial nerves are key to our taste. Damage to them can cause disorders like ageusia or dysgeusia. These issues can really impact someone’s life, making it important to know how they relate to cranial nerve problems.

Ageusia, Hypogeusia, and Dysgeusia

Taste disorders come in different forms. Ageusia is when you can’t taste anything. Hypogeusia means you can’t taste as well. Dysgeusia makes food taste wrong, like it’s metallic or bitter.

Ageusia means you can’t taste at all. Hypogeusia makes it hard to enjoy food because you can’t taste it well. Dysgeusia makes food taste bad, even if it’s not supposed to.

Taste Disorder | Description | Common Causes |

Ageusia | Complete loss of taste | Damage to facial, glossopharyngeal, or vagus nerves |

Hypogeusia | Reduced taste sensitivity | Nerve damage, certain medications, aging |

Dysgeusia | Distorted taste perception | Nerve damage, dry mouth, certain medications |

Bell’s Palsy and Facial Nerve Taste Disruption

Bell’s palsy causes facial muscle weakness or paralysis. It happens when the facial nerve gets inflamed or compressed. This can mess up taste, mainly on the front part of the tongue.

People with Bell’s palsy might not taste food right on one side of their tongue. Knowing how Bell’s palsy affects taste can help manage it better.

Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia and Taste Disturbances

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is a rare condition. It causes sharp pain in the tongue, throat, or ear. This pain comes from the glossopharyngeal nerve getting irritated.

This condition can also mess up taste, mainly on the back part of the tongue. To fix taste problems, you need to treat the neuralgia.

Vagus Nerve Injuries and Their Effect on Taste

The vagus nerve helps with taste, mainly in the epiglottis and pharynx. Damage to it can cause taste issues, like dysgeusia or feeling like you’re gagging.

Vagus nerve injuries can happen for many reasons, like surgery or trauma. Knowing how the vagus nerve affects taste helps diagnose and treat taste disorders.

Modern Research on Taste Perception

Modern research has opened up new areas in taste perception. It includes the role of umami and how genetics affect our taste. We’re learning more about how our brains handle the complex sensations of taste.

Beyond the Basic Tastes: Umami and Others

For a long time, we thought there were only four basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. But now, we know there’s a fifth: umami. It’s often called the savory taste.

Umami is detected by special taste receptors on our tongues. These receptors are sensitive to glutamate, an amino acid in many foods. This taste enhances the flavor of our food.

Genetic Variations in Taste Perception

Genetics play a big role in how we taste things. Some people are more sensitive to certain tastes because of their genes.

For example, the ability to taste PROP is based on genetics. Some people, called “supertasters,” have more taste buds. This makes them more sensitive to tastes.

Genetic Variation | Taste Perception Impact |

PROP tasters | Increased sensitivity to bitter tastes |

Non-tasters | Reduced sensitivity to certain bitter compounds |

Neuroplasticity in the Gustatory System

Neuroplasticity is key in the gustatory system. It shows that our brain’s sensory areas can change. This idea challenges the old belief that these areas are fixed.

Studies have found that the gustatory cortex can adapt. It changes based on our experiences and environment. This adaptability helps us enjoy a wide range of flavors.

Clinical Implications of Taste Dysfunction

Taste problems can greatly affect a person’s life and health. When taste is off, it can cause many issues. These issues can harm a person’s health and happiness.

Impact on Nutrition and Quality of Life

Taste is key in choosing and eating food. People with taste issues might eat less or differently. This can lead to not getting enough nutrients, which can make health problems worse.

Also, enjoying food is tied to taste. Those with taste problems might find eating less fun. This can make life less enjoyable. It can also make social times around food less fun, leading to feeling alone.

Taste Changes in Aging and Disease

As we age, our taste can change. Older people might have fewer taste buds or different taste experiences. This can make it hard to get the nutrients they need.

Many diseases and conditions can also mess with taste. This includes brain problems, infections, and not getting enough nutrients.

- Neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease can affect taste.

- Certain infections, including those affecting the oral cavity, can alter taste perception.

- Nutritional deficiencies, such as zinc, can impact taste function.

Therapeutic Approaches to Taste Disorders

Dealing with taste problems needs a variety of solutions. Some cases can’t be fixed, but others can be helped. Doctors might treat the underlying cause, change medications, or give nutrition advice.

In some cases, special treatments can help. For example, taking zinc can help if you’re not getting enough. Researchers are also looking into new ways to help, like medicines and taste training.

Conclusion

We’ve looked into how we taste things and the key role of cranial nerves. The facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves help us taste the five basic tastes. If they don’t work right, it can cause big problems.

Our findings show how these nerves are vital for tasting. The facial nerve handles taste on the front of the tongue. The glossopharyngeal nerve is for the back third. The vagus nerve is key for taste in the throat.

Knowing how these nerves work is key to fixing taste problems. If they don’t work, it can mess up our eating and life quality. As we learn more, we can find better ways to treat taste issues.

In short, the connection between cranial nerves and taste is complex. By reviewing the main points, we stress the need for more research and awareness.

FAQ

Which cranial nerves are involved in transmitting taste sensations?

The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX), and vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) carry taste information. They do this from different parts of the tongue and mouth.

What is the role of the facial nerve in taste perception?

The facial nerve sends taste signals to the front two-thirds of the tongue. It does this through its chorda tympani branch. This branch helps us taste sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

How does the glossopharyngeal nerve contribute to taste?

The glossopharyngeal nerve sends taste signals from the back third of the tongue to the brain.

What is the function of the vagus nerve in taste perception?

The vagus nerve sends taste signals from the epiglottis and throat to the brain. It helps us taste in these areas, which is important for reflexes like gagging.

How is taste information processed in the brain?

Taste information starts in the nucleus solitarius of the medulla oblongata. It then goes through the thalamic relay and ends in the gustatory cortex. This is where our brain processes taste.

What is the difference between the olfactory nerve and the nerves responsible for taste?

The olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I) deals with smell. The facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves handle taste. Together, smell and taste create flavor.

How is taste function assessed clinically?

Doctors use electrogustometry, taste strips, whole-mouth taste testing, and regional taste testing to check taste. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses.

What are some common taste disorders and their causes?

Taste disorders like ageusia (loss of taste), hypogeusia (reduced taste), and dysgeusia (distorted taste) can happen. They can be caused by problems with the nerves involved in taste, like Bell’s palsy affecting the facial nerve.

How do genetic variations affect taste perception?

Genetic differences can change how we taste things. Some people might be more sensitive to certain tastes because of their genes.

What is the impact of taste dysfunction on nutritional status and quality of life?

Taste problems can lead to nutritional issues and lower quality of life. Not being able to enjoy food can affect our eating habits and health.

Are there therapeutic strategies to manage taste disorders?

Yes, there are ways to manage taste disorders. Doctors can treat underlying causes and use medications or other methods to help improve taste.

References

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Evidence-Based Medical Guidance. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7769831/