Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The testes are paired, oval-shaped organs in the scrotum. They have two main jobs: making sperm (spermatogenesis) and producing androgens, mainly testosterone. Testicular cancer happens when cells in this tissue become malignant. Most cases (over 90%) start in the germinal epithelium and are called Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. This cancer stands out because of its origins in early development, its unique way of spreading, and its high sensitivity to treatment, making it one of the most curable cancers even when it has spread.

Today, doctors see testicular cancer as a problem that starts with abnormal development of germ cells, not just a random cancer event. The current model suggests that the first changes happen during fetal development. Some early germ cells, which should become sperm, get stuck and do not mature. These cells, called Germ Cell Neoplasia In Situ, can stay inactive in the testicle for years. When puberty starts and hormone levels rise, these cells can become active again, start to grow, and eventually form tumors. This means testicular cancer is linked to events from before birth through young adulthood, connecting early development to cancer later in life.

From the perspective of regenerative biology, the testis is an organ of immense proliferative capacity. The spermatogonial stem cells possess the unique ability to self-renew and differentiate into haploid gametes throughout the male lifespan. Malignancy represents a corruption of this high-fidelity regenerative process. In Seminomas, the tumor cells retain a primitive, gonocyte-like phenotype, maintaining totipotency (the ability to differentiate into any cell type) but lacking the instructions to organize into tissues. In Non-Seminomas, the cells attempt to differentiate into embryonic structures (embryonal carcinoma), extra-embryonic tissues like the yolk sac or placenta (yolk sac tumor and choriocarcinoma), or somatic tissues (teratoma). Thus, testicular cancer is a chaotic caricature of embryogenesis, in which the uncontrolled proliferation of pluripotent cells mimics the early stages of human development in a disorganized, destructive manner.

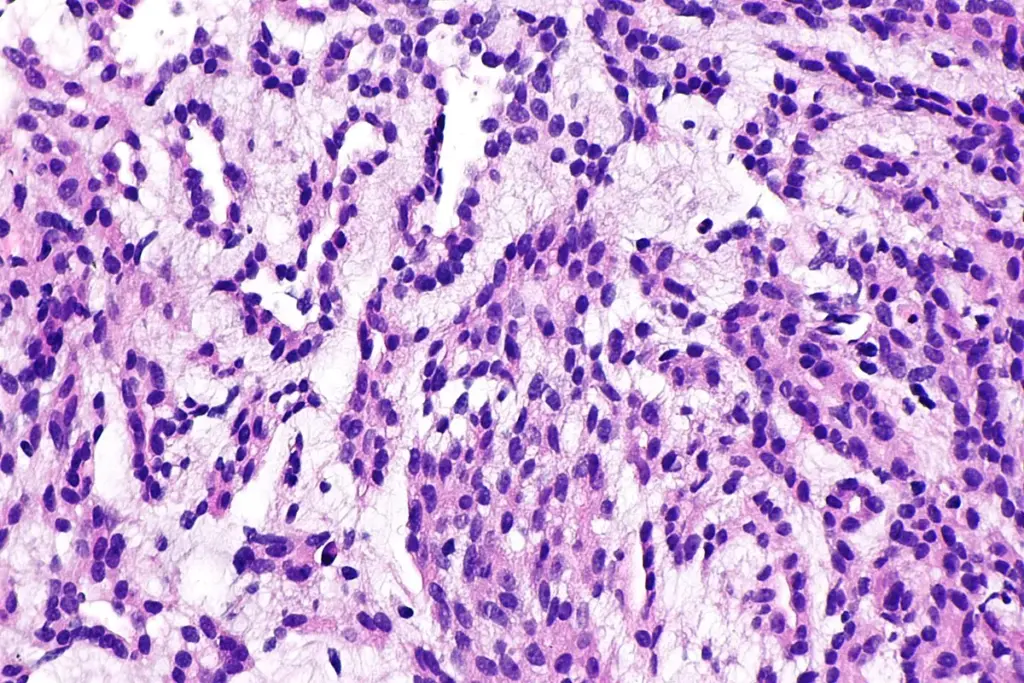

Classifying testicular cancer by how it looks under the microscope is key for treatment. There are two main types: Seminoma and Non-Seminomatous Germ Cell Tumors. Seminomas have cells that look like early germ cells from embryos. They usually grow slowly, respond very well to radiation and chemotherapy, and often stay in the lymph nodes for a long time. Seminomas also tend to have many immune cells around them, showing the body is trying, but not quite able, to fight the cancer.

Non-seminomas are more aggressive and varied. They often have a mix of different cell types. Embryonal carcinoma cells are very undifferentiated and can quickly invade blood vessels. Choriocarcinoma parts act like placenta cells, make a lot of hCG, and tend to spread early to the lungs and brain. Yolk sac tumor parts look like early gut or liver tissue and produce AFP. Teratomas can have tissues like cartilage, bone, nerve, or skin. Because these tumors are so mixed, they need a combination of treatments, since each cell type may respond differently.

Molecular Drivers and Genomic Instability

Modern research groups testicular cancer within the broader framework of Testicular Dysgenesis Syndrome (TDS). This hypothesis suggests that environmental exposures or genetic defects during early fetal life disrupt the hormonal environment required for proper gonadal development. This disruption leads to a constellation of reproductive disorders that share a common origin: cryptorchidism (undescended testes), hypospadias (urinary tract malformation), subfertility, and germ cell cancer.

In this context, the tumor is the final manifestation of a poorly formed organ. The Sertoli cells, which act as “nurse” cells providing structural and metabolic support to developing sperm, may fail to mature properly in TDS. Immature Sertoli cells cannot efficiently eradicate the arrested fetal germ cells (the precursors to cancer), allowing them to persist into adulthood. This biological overview shifts the focus from purely treating a tumor to understanding the patient’s entire reproductive health history. It implies that the contralateral, “healthy” testis may also harbor subtle defects or pre-malignant changes, necessitating vigilant lifelong surveillance of the entire urogenital system.

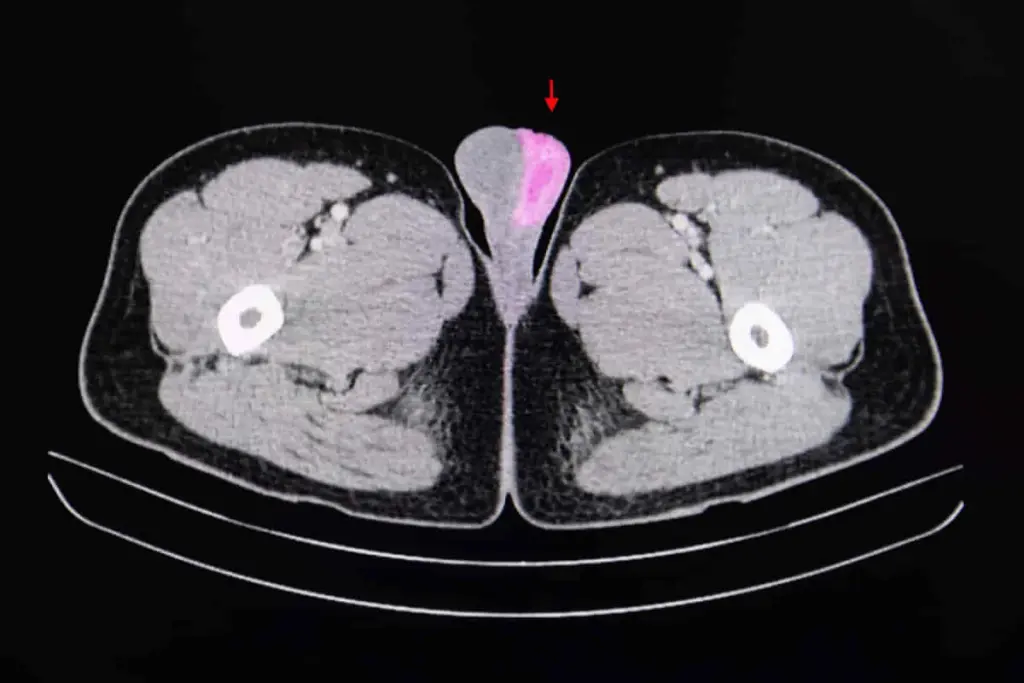

Testicular cancer care is changing quickly thanks to new technology. Instead of just looking at where the cancer is, doctors now use genetic tests to better understand each case. Advanced DNA sequencing helps find out why some rare patients do not respond to standard chemotherapy. Modern treatment plans use blood tests for tumor markers to guide both diagnosis and track how the tumor shrinks during treatment, allowing doctors to adjust therapy as needed.

Fertility preservation has also improved a lot. Since testicular cancer often affects men during their most fertile years, saving sperm is very important. New freezing methods, like vitrification, help keep sperm healthy for future use. If a man has no sperm in his semen because of the tumor, doctors can sometimes retrieve sperm directly from the testicle during surgery. This approach combines cancer treatment with fertility care, reflecting a more complete way of looking after patients.

The study of testicular cancer has provided profound insights into the general field of stem cell biology. Embryonal carcinoma cells, the stem cells of non-seminomas, are essentially malignant equivalents of human embryonic stem cells. They express the same pluripotency markers, such as OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2. By studying how these cancer cells maintain their “stemness,” researchers gain knowledge about how to manipulate normal stem cells for regenerative therapies. Conversely, differentiation therapy aims to force these malignant stem cells to mature into benign, non-proliferative tissues (teratoma), effectively “normalizing” the cancer rather than killing it. This intersection of oncology and regenerative medicine holds the promise of novel treatments that reprogram the cancer cell’s destiny.

Key Physiological Functions Compromised

The testis is an immunologically privileged site, meaning it is largely hidden from the body’s adaptive immune system to protect the developing sperm (which are haploid and foreign to the body) from autoimmune attack. The blood-testis barrier and a specialized immunosuppressive microenvironment maintain this privilege. Testicular tumors exploit this privilege. They grow in a sanctuary site that naturally dampens immune surveillance.

However, once the tumor breaches the barrier and metastasizes to lymph nodes or visceral organs, it encounters the full force of the immune system. The intense lymphocytic infiltration observed in seminomas represents the host’s attempt to reject the tumor. Modern immunotherapy approaches, such as Checkpoint Inhibitors (PD-1/PD-L1 blockade), aim to augment this natural immune response, particularly in rare cases of multi-drug resistant disease. The definition of the disease thus includes its status as an “immunologically hot” tumor that interacts dynamically with host defense mechanisms.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Germ Cell Neoplasia In Situ is the non-invasive precursor lesion to most testicular cancers. These are cells that stalled in their development during fetal life and remained dormant in the testicle. They are not yet cancerous but have a high potential to transform into invasive seminoma or non-seminoma. GCNIS is typically found in the tissue surrounding a tumor or, rarely, in the opposite testicle.

The blood-testis barrier allows the testicle to be an “immunologically privileged” site, protecting developing cells from the body’s immune system. Cancer cells can exploit this protected environment to grow undetected by immune surveillance. Once the cancer grows large enough to break this barrier, it interacts with the immune system, often triggering an inflammatory response.

Unlike cancers caused by aging or environmental toxins, testicular cancer arises from errors in fetal development. The cells that form the tumor are meant to become sperm, but get stuck in an embryonic state. Therefore, the biology of the cancer mimics that of a developing embryo, growing rapidly and sometimes forming different types of tissue, such as cartilage or hair (in teratomas).

Seminomas arise from young germ cells and tend to grow more slowly and remain localized longer. They are susceptible to radiation. Non-seminomas are composed of more mature, specialized cancer cells that can mimic fetal tissues (yolk sac, placenta). Non-seminomas tend to grow more quickly and spread to other parts of the body earlier.

Yes, Isochromosome 12p (i12p) is a specific genetic abnormality found in almost all testicular germ cell tumors. It involves an extra copy of the short arm of chromosome 12. This genetic marker confirms the diagnosis of a germ cell tumor at a molecular level and is a key driver of the cancer’s ability to survive and multiply.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)