Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The thyroid gland is an important endocrine organ in the front of the neck, sitting over the trachea and shaped like a butterfly. Although it is small, weighing only about fifteen to twenty grams in adults, it has a major impact on the body’s metabolism. The gland has two side lobes joined by a central piece of tissue called the isthmus. It has a rich blood supply from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, which supports its high metabolic activity and allows it to quickly release hormones, as well as potentially malignant cells, into the bloodstream.

The thyroid acts like the body’s thermostat. Its main job is to take iodine from the blood and use it to make thyroid hormones: thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These hormones control the body’s basic metabolic rate, affecting heart rate, body temperature, energy use, and protein production. The thyroid’s activity is carefully regulated by a feedback system involving the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which release Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). In cancer care, this is important because TSH helps thyroid cells grow, so lowering TSH is a key part of treating differentiated thyroid cancer to prevent it from coming back.

The thyroid gland has two main types of hormone-producing cells, which are the starting points for different thyroid cancers. Most of the gland is made up of follicular cells, which make T3 and T4 hormones and form small round structures called follicles. These cells can concentrate iodine, a feature used in thyroid cancer treatment. The other type, called parafollicular cells or C-cells, are found between the follicles and make calcitonin, a hormone that controls calcium levels. Cancers that start in follicular cells act very differently from those that start in C-cells, so they need different tests and treatments.

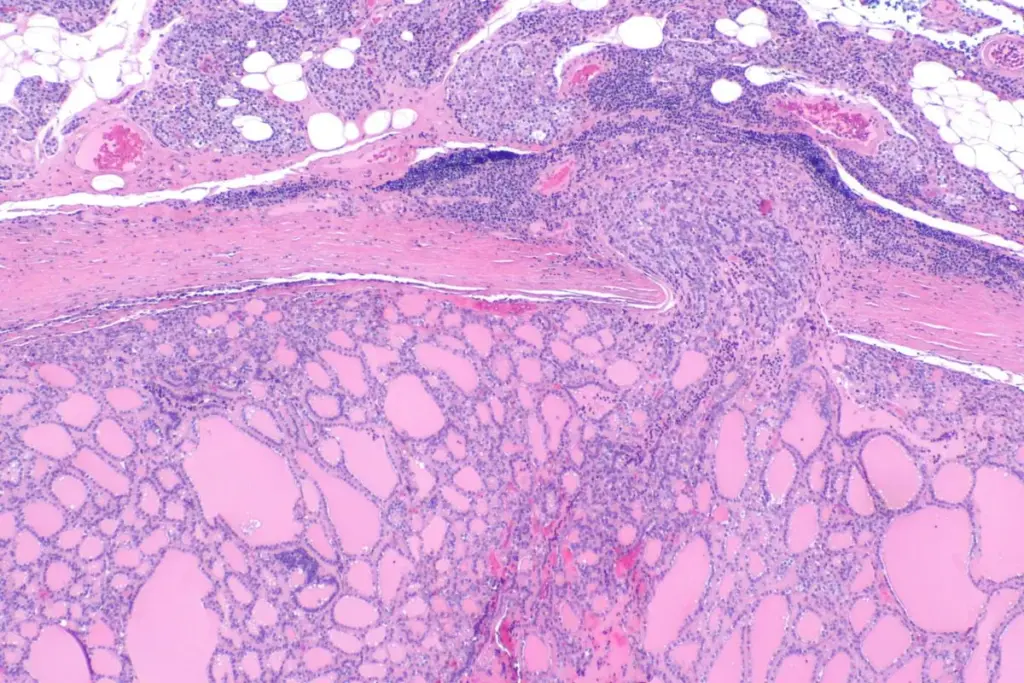

The vast majority of thyroid malignancies fall under the umbrella of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer (DTC). The term differentiated implies that the cancer cells still closely resemble normal thyroid cells under a microscope and retain many of their functional properties, such as the ability to take up iodine and produce thyroglobulin. Within this category, Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (PTC) is the most prevalent subtype, accounting for approximately eighty to eighty-five percent of all thyroid cancers. PTC is characterized by slow growth and a tendency to spread to the neck lymph nodes initially. Despite this lymphatic spread, the prognosis for PTC is generally excellent, with high long-term survival rates.

Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma (FTC) is the second most common type. Unlike papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma rarely spreads to lymph nodes. Instead, it tends to spread through the bloodstream to places like the lungs and bones. Diagnosing follicular carcinoma is challenging because its cells can look like those in harmless growths called adenomas. To confirm cancer, doctors must see that the tumor has invaded the capsule or blood vessels, which usually can’t be determined with a needle biopsy alone and often requires surgery to remove the lobe.

Hürthle Cell Carcinoma is a type of differentiated thyroid cancer. It was once thought to be a kind of follicular carcinoma, but now it is seen as its own type. Hürthle cells have many mitochondria, which makes them look different under a microscope. These tumors can be more aggressive than regular follicular cancers and often do not absorb radioactive iodine well, which makes them harder to treat if they spread.

Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC) is a type of thyroid cancer that comes from parafollicular C-cells, not follicular cells. Because of this, MTC does not make thyroglobulin and does not absorb iodine. Instead, these tumors release high levels of calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which are useful markers for diagnosis and follow-up. MTC is also notable for its strong genetic link; about a quarter of cases are inherited and related to Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) syndromes caused by RET gene mutations. Since these tumors do not respond to radioactive iodine or TSH suppression, surgery is the main treatment.

At the most aggressive end of the spectrum is Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC). Fortunately rare, accounting for less than two percent of cases, ATC is undifferentiated, meaning the cells have lost all resemblance to normal thyroid tissue. These cells divide rapidly and invade surrounding structures, such as the trachea, esophagus, and major blood vessels, at an alarming speed. ATC is considered a systemic disease from the time of diagnosis and is one of the most lethal human malignancies.

When a well-differentiated thyroid cancer changes into an undifferentiated anaplastic cancer, this process is called dedifferentiation. It usually happens because of new genetic mutations, like those in the TP53 gene. It is important to understand that thyroid cancer is not just one disease, but a group of different conditions that can range from slow-growing papillary microcarcinoma to very aggressive anaplastic carcinoma.

The understanding of thyroid cancer has been revolutionized by molecular genetics. We now know that specific genetic alterations drive the formation and progression of these tumors. In Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma, the most common driver mutation is BRAF V600E. This mutation activates the MAPK signaling pathway, leading to uncontrolled cell division. Tumors with BRAF mutations tend to be more aggressive, with a higher likelihood of spreading to lymph nodes and recurring after treatment.

Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma is more commonly associated with RAS mutations or PAX8-PPARgamma chromosomal rearrangements. These genetic signatures drive follicular growth patterns and the tendency toward vascular invasion. In Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma, the RET proto-oncogene is the central player. Germline (inherited) mutations in RET cause the hereditary forms of the disease, while somatic (acquired) RET mutations are found in many sporadic cases.

Identifying these molecular markers is no longer purely academic. It has entered clinical practice. When a biopsy result is indeterminate, molecular testing can be performed on the sample to detect these mutations, helping determine whether surgery is necessary. Furthermore, in advanced disease, these mutations serve as targets for new drugs. For example, tyrosine kinase inhibitors that specifically target BRAF or RET proteins are now used to treat patients with advanced, metastatic thyroid cancer who no longer respond to standard radioactive iodine therapy.

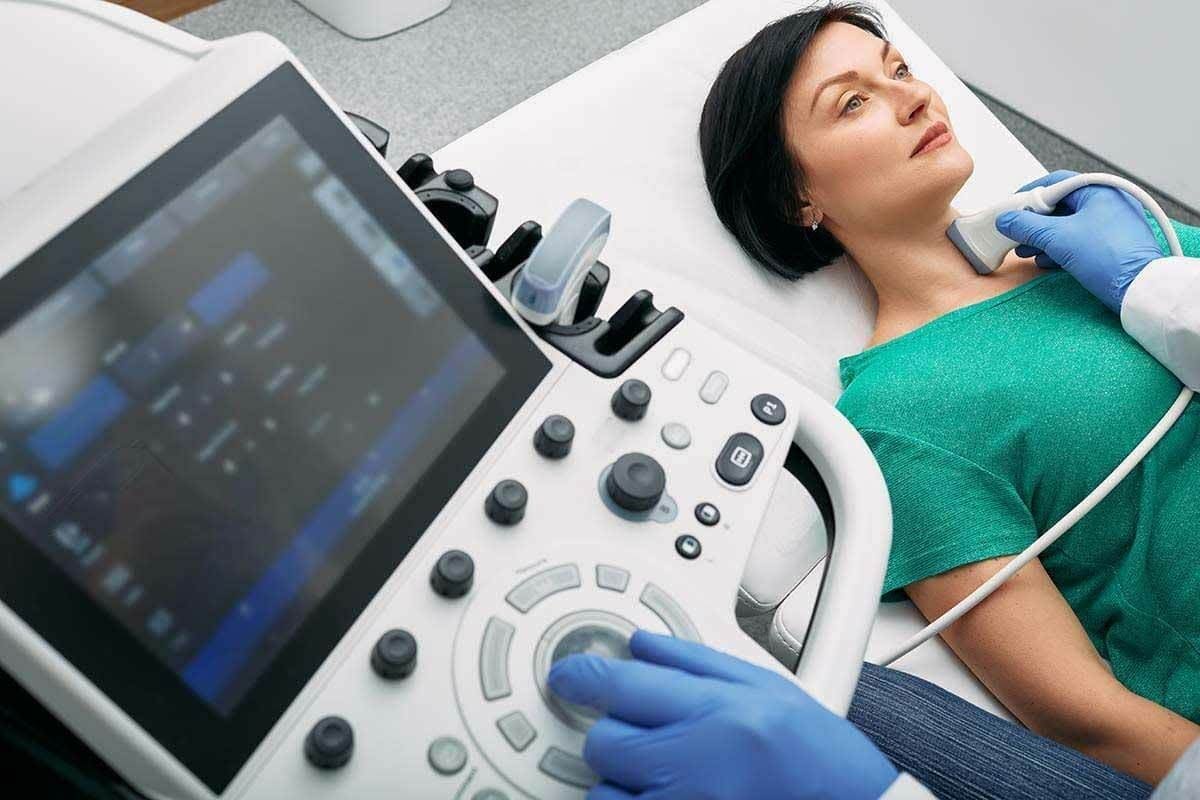

Thyroid cancer has seen a faster rise in incidence than almost any other malignancy over the past few decades. However, this statistic requires careful interpretation. Much of this “epidemic” is attributed to overdiagnosis—the detection of small, indolent cancers that would likely never have caused symptoms or death during the patient’s lifetime. The widespread use of high-resolution ultrasound and other imaging modalities has led to the incidental discovery of sub-centimeter thyroid nodules, known as papillary microcarcinomas.

Even though more thyroid cancers are being found, the death rate has stayed about the same. This means many of the cancers being detected are not dangerous. As a result, doctors are changing how they treat thyroid nodules. Instead of treating every nodule aggressively, they now use a risk-based approach. For some patients with small, low-risk tumors, doctors may recommend active surveillance, which means monitoring the tumor closely instead of doing surgery right away.

Not all of the rise in thyroid cancer cases is from overdiagnosis. There is also a real increase in larger, more advanced cancers, which may be related to factors like obesity or exposure to certain chemicals. The main challenge for doctors is to tell the difference between slow-growing cancers that need little treatment and aggressive cancers that need more intensive therapy, so patients get the right care without being over- or under-treated.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Hyperthyroidism is a functional disorder where the gland produces too much hormone, causing symptoms like a racing heart and weight loss. Thyroid cancer is a structural disorder involving the growth of malignant cells. While they can coexist, having an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) actually makes it statistically less likely that a thyroid nodule is cancerous, as “hot” or functioning nodules are rarely malignant.

No. A goiter is simply a non-specific term for an enlarged thyroid gland. It can be caused by iodine deficiency, autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto’s, or multiple benign nodules (multinodular goiter). While thyroid cancer can present as a goiter or within a goiter, the presence of an enlarged gland does not inherently mean cancer is present.

For the most common types, such as papillary and follicular thyroid cancer, the survival rates are among the highest of all cancers. The 5-year survival rate for localized differentiated thyroid cancer approaches ninety-nine percent. However, survival is significantly lower for the rare anaplastic and advanced medullary subtypes, which is why correct typing is crucial.

Most thyroid cancers are sporadic, meaning they occur by chance. However, Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma has a strong hereditary component (about 25% of cases). There is also a condition called Familial Non-Medullary Thyroid Cancer, where papillary or follicular cancers appear in families, often behaving slightly more aggressively than sporadic cases.

The term differentiated refers to how closely the cancer cells resemble normal cells. In differentiated thyroid cancer, the cells still look very similar to healthy thyroid cells under a microscope and retain the ability to absorb iodine. This is a good thing because it allows doctors to use radioactive iodine to target and treat the cancer cells specifically.

We often see patients with hypothyroidism, a condition where the thyroid gland doesn’t make enough thyroid hormones. The ICD-10 code E03.9 is for “hypothyroidism, unspecified.”

Radioactive iodine (RAI) is a common treatment for Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer. Studies show it doesn’t shorten life for most patients. It might even

Getting the thyroid gland checked right is key to good health. MRI and ultrasound help a lot in checking how well the thyroid is working.

The thyroid gland is a key part of our body, found in the neck. It helps control how our body grows and works. At Liv

At Liv Hospital, we know how important an accurate diagnosis is for your health. A CT scan of the thyroid gland is key. It helps

Understanding Thyroid Gland X-Ray and Ultrasound Knowing the normal size of the thyroid gland is key to detecting issues early. At Liv Hospital, we use

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)