Clinical Immunology focuses on the immune system’s health. Learn about the diagnosis and treatment of allergies, autoimmune diseases, and immunodeficiencies.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, often called SLE or just lupus, is a classic example of a systemic autoimmune disease. It is a long-term condition where the immune system cannot tell the difference between harmful invaders and the body’s own cells. As a result, the body makes autoantibodies that attack healthy tissues. Lupus is sometimes called the great imitator because it can affect almost any organ, such as the skin, joints, kidneys, brain, heart, and lungs.

Lupus symptoms can look very different from one person to another. Some people have only mild skin or joint problems, while others may develop serious issues like kidney failure or severe nerve problems. The disease is caused by immune complexes—clusters of antigens and antibodies—that travel in the blood and settle in tissues, causing inflammation and damage.

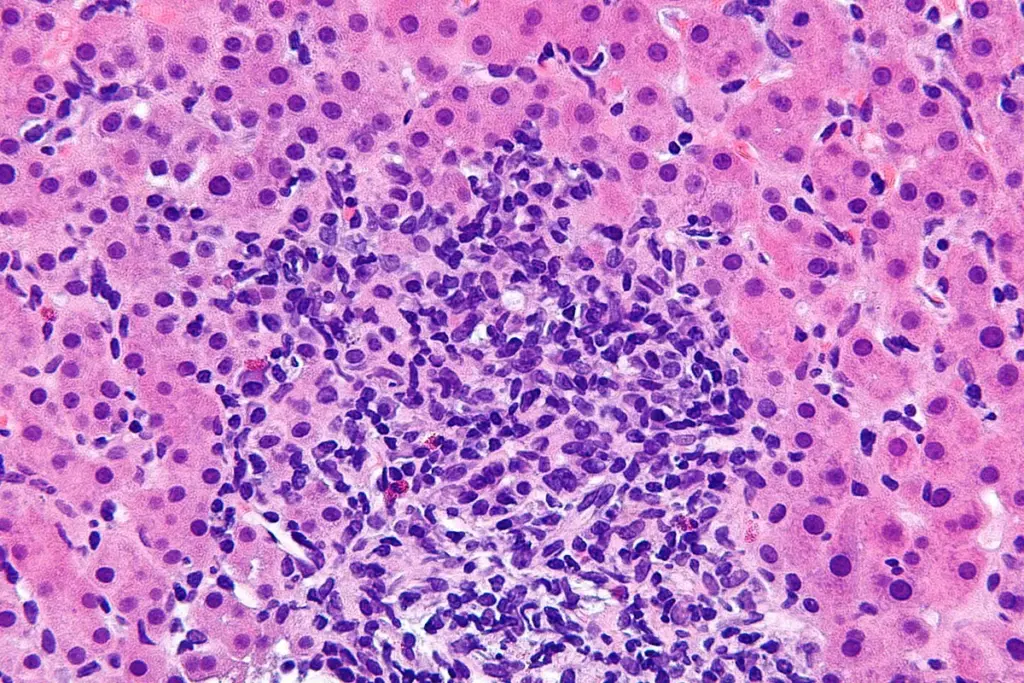

The fundamental defect in lupus is a failure of the immune system to maintain tolerance to self-antigens, particularly those found within the cell nucleus. In a healthy individual, the body has checkpoints to eliminate immune cells that target its own tissues. In lupus, these checkpoints fail. B lymphocytes become hyperactive and produce autoantibodies against nuclear components like DNA and RNA. Simultaneously, T lymphocytes, which regulate the immune response, fail to suppress these overactive B cells. This dysregulation is further compounded by a defect in the clearance of apoptotic cells. When cells die naturally, they are usually cleared efficiently. In lupus patients, this clearance is delayed, exposing the immune system to nuclear materials that it mistakes for viral particles. This triggers an interferon signature, a high state of immune alert that perpetuates chronic inflammation.

Recent studies show that Type I interferons play a key role in lupus. These proteins are normally released when the body fights viruses. In lupus, the body behaves as if it is fighting a constant viral infection, even when there is none. Many patients have high levels of interferon alpha in their blood, which matches how active their disease is. This triggers other immune cells and creates a cycle of inflammation that can damage organs over time.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus is the most common and serious type, but it is important to know about other forms of lupus to understand the full range of the disease.

This type of lupus mainly affects the skin. It causes round, red, scaly, and crusty patches called discoid lesions. If these appear on the scalp, they can leave scars and cause permanent hair loss. Most people with discoid lupus do not have serious problems with their internal organs, though a few may go on to develop systemic lupus. Doctors usually confirm the diagnosis with a skin biopsy, which shows a typical pattern called interface dermatitis.

Some medicines can cause a temporary type of lupus. Drugs like hydralazine, procainamide, and isoniazid are well-known examples, and some newer biologic drugs can also trigger it. The symptoms usually look like mild systemic lupus, with joint pain and chest pain from pleurisy, but it rarely affects the kidneys or brain. The main difference is that this form usually goes away after stopping the medication that caused it.

Neonatal lupus is a rare condition that affects babies born to mothers with lupus or Sjögren syndrome who have certain antibodies called Anti Ro or Anti La. These antibodies can pass through the placenta and cause a temporary rash or blood problems in the baby. The most serious issue is congenital heart block, which is permanent and may need a pacemaker. However, the skin and blood symptoms usually go away within six months as the mother’s antibodies leave the baby’s body.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus affects people worldwide, but some groups are affected more than others.

Lupus usually comes and goes in cycles. People have flares, when symptoms get worse, and remissions, when symptoms improve or disappear. Doctors aim to reduce how often and how badly flares happen to protect organs from long-term damage. Even mild, ongoing inflammation can speed up hardening of the arteries, raising the risk of heart attacks and strokes, which are major health concerns for people with lupus.

The definition of lupus extends beyond biological markers to the lived experience of the patient. The disease imposes a significant burden on daily life. Fatigue is the most common and often the most debilitating symptom, affecting physical and cognitive function. Patients often describe a fog that makes concentration difficult. The unpredictability of flares can create anxiety and necessitate adjustments in career and social planning. Furthermore, the visible manifestations of the disease, such as skin rashes, can impact body image and psychological well-being.

Historically, lupus was considered a fatal disease with a poor prognosis. However, with the advent of corticosteroids, immunosuppressive therapies, and better management of comorbidities, the survival rate has improved dramatically. Today, the 10-year survival rate exceeds 90 percent in developed nations. The focus of clinical care has shifted from keeping patients alive to preventing long-term damage and maximizing quality of life. However, mortality remains higher than that of the general population, driven primarily by active disease in the early years and cardiovascular complications or infection in the later years.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

It is a chronic autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks healthy tissues, potentially affecting the skin, joints, kidneys, and other organs

No. Lupus is an autoimmune condition and cannot be spread from person to person through contact or proximity.

Its symptoms vary widely and often mimic other diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, blood disorders, or Lyme disease, making diagnosis challenging.

Yes. While it is far more common in women, men can develop lupus and often experience a more severe disease course with higher rates of kidney involvement.

There is currently no cure, but effective treatments exist to manage symptoms, induce remission, and prevent organ damage.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)