Geriatrics addresses the health needs of older adults, focusing on frailty, dementia, falls, and chronic disease management.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The management of hypertension has evolved into a strategic discipline that transcends the simplistic goal of lowering numbers. The contemporary objective is the preservation and restoration of target organs—the heart, brain, and kidneys—while minimizing the systemic burden of vascular resistance. Treatment is now conceptualized as a lifelong partnership between patient and clinician, utilizing a multimodal approach that integrates established pharmacotherapy with the principles of vascular biology and, increasingly, insights from regenerative medicine. The focus is on reversing the structural remodeling of the blood vessels, reducing endothelial inflammation, and preventing the exhaustion of the body’s intrinsic repair mechanisms.

Care pathways are stratified based on cardiovascular risk. For some, lifestyle modification is the primary intervention; for others, a complex regimen of multiple agents is required to achieve hemodynamic stability. In all cases, the “treat to target” approach ensures that therapy is aggressive enough to protect organs but tailored to avoid adverse effects, particularly in frail or elderly populations.

Modern antihypertensive medications are designed to intervene at specific points in the physiological pathways that regulate blood pressure. They are often used in combination to achieve a synergistic effect, attacking the problem from multiple angles to reset the vascular tone.

While standard drugs manage the condition, the field of regenerative medicine explores therapies that could theoretically cure or significantly reverse the vascular pathology. These approaches are largely investigational but represent the future of care.

The effectiveness of any treatment relies entirely on adherence. Hypertension requires daily management, often for decades. Care protocols now emphasize systems to support the patient.

A subset of patients fails to achieve control despite the use of three or more medications. This condition, resistant hypertension, requires a specialized evaluation.

Ultimately, treatment is about vascular protection. Every millimeter of mercury reduction translates to a significant decrease in the risk of stroke and heart failure; however, the choice of drug matters. Clinicians favor agents that offer “pleiotropic” effects—benefits beyond pressure reduction. For example, statins are often prescribed alongside antihypertensives not just for cholesterol, but because they improve endothelial function and reduce vascular inflammation.

The care of the hypertensive patient is a meticulous process of tuning the cardiovascular system. It involves balancing the physics of flow with the biology of the vessel wall. By integrating robust pharmacological blockades with strategies that preserve vascular structure, modern medicine aims to convert a progressive, damaging disease into a manageable, stable condition, maintaining the patient’s vitality and longevity.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

While targets can vary based on individual risk profiles and age, most major guidelines recommend a target below 130/80 mmHg for the general adult population. For older adults or those with specific comorbidities, the target might be slightly looser to prevent dizziness and falls. The goal is to lower pressure as much as tolerated to minimize the risk of cardiovascular events without causing adverse side effects.

Hypertension is a complex condition driven by multiple physiological pathways—fluid volume, hormone levels, and vessel constriction. Using a single drug often activates compensatory mechanisms that counteract the drug’s effect. Combining drugs that work on different pathways (e.g., a diuretic with an ACE inhibitor) is usually more effective, allows for lower doses of each medication (reducing side effects), and provides better long-term protection for the heart and kidneys.

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above the treatment target despite the concurrent use of three antihypertensive drug classes, commonly including a long-acting calcium channel blocker, a blocker of the renin-angiotensin system (ACE or ARB), and a diuretic. It requires a specialized workup to rule out secondary causes (such as sleep apnea) and often necessitates the addition of specific medications, such as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

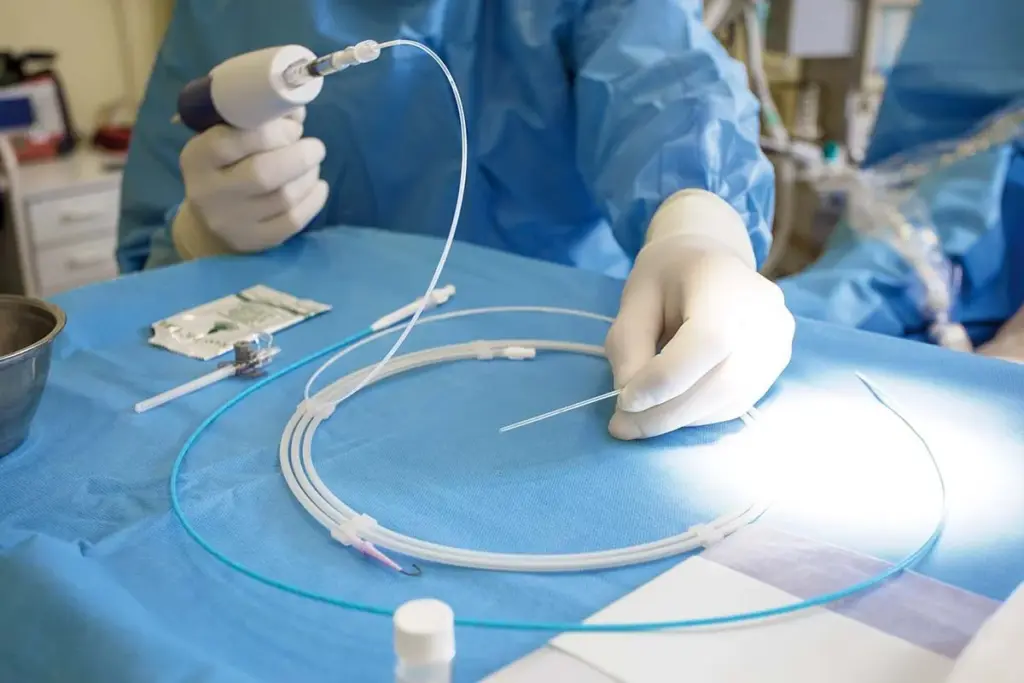

Renal denervation is a minimally invasive procedure designed for patients with uncontrolled hypertension. It involves inserting a catheter into the renal arteries (the arteries supplying the kidneys) and using energy (radiofrequency or ultrasound) to disrupt the overactive sympathetic nerves surrounding the arteries. By quieting these nerves, the procedure reduces signals that tell the body to raise blood pressure, helping lower blood pressure in patients who haven’t responded to medication alone.

In most cases of primary hypertension, medication is a lifelong commitment because the underlying tendency for high blood pressure persists. However, significant lifestyle changes—such as massive weight loss, dietary shifts, and exercise—can sometimes improve blood pressure to the point where medication dosages can be reduced or, in rare cases, discontinued under medical supervision. The “cure” is usually control; stopping medication without a doctor’s approval typically leads to a rebound in pressure.