Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

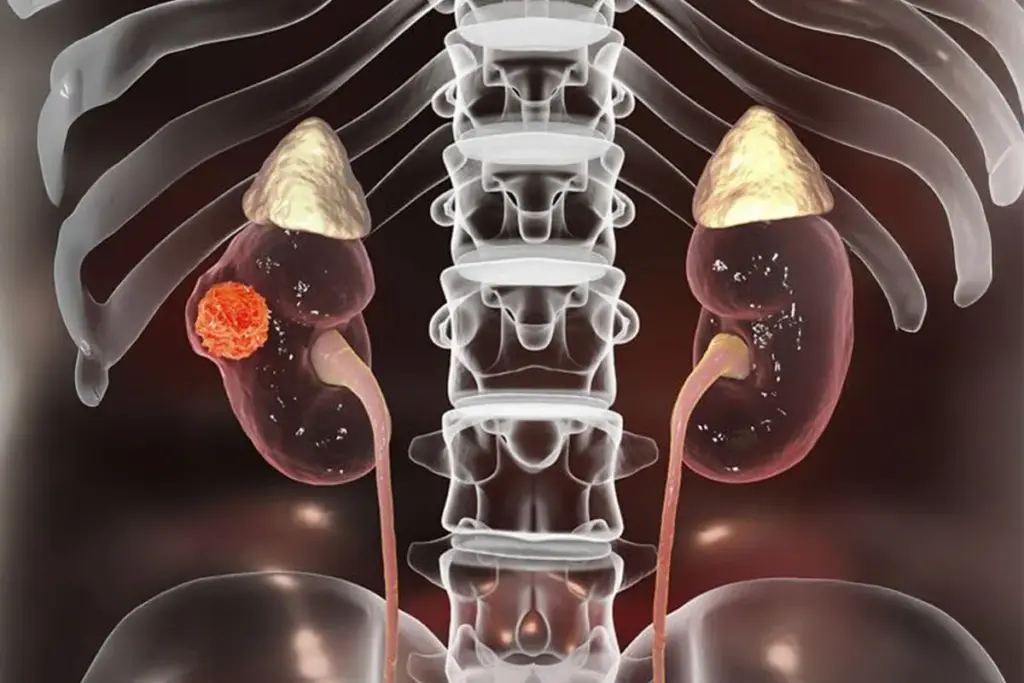

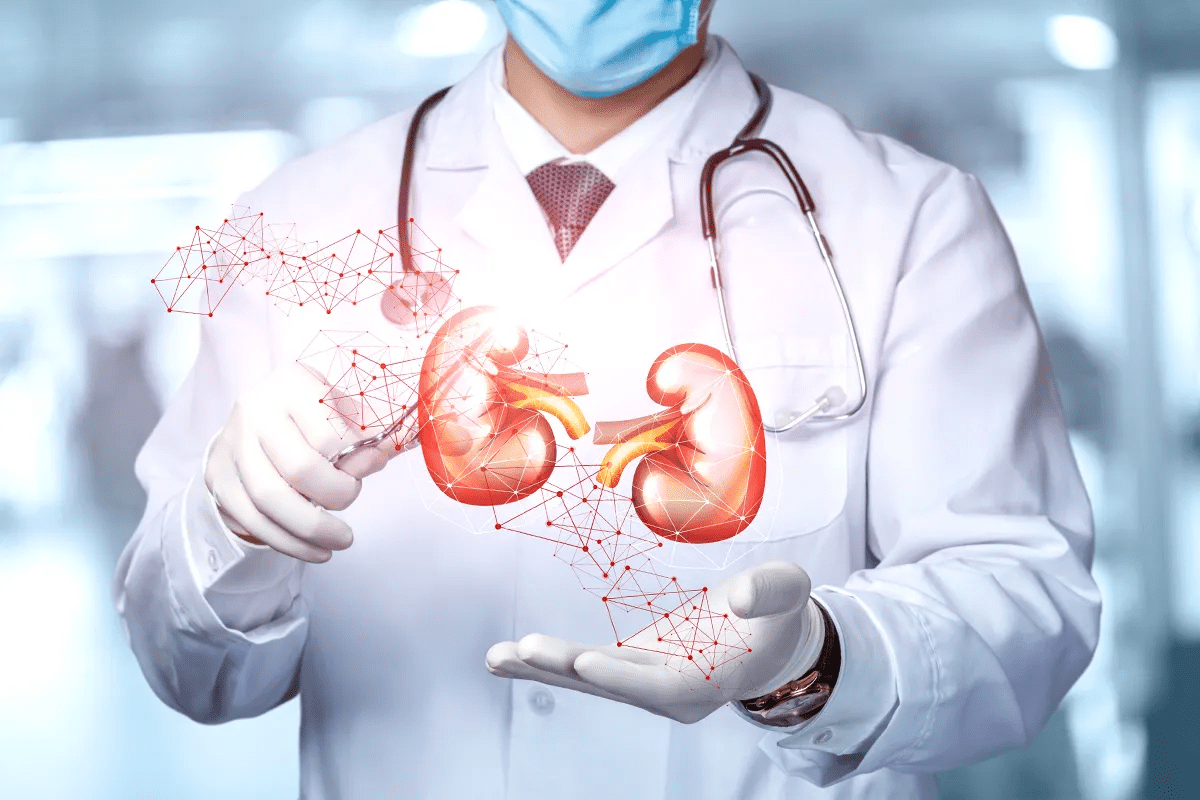

The renal system is a key part of the body’s filtration and balance. The kidneys, found in the back of the abdomen, filter blood, balance electrolytes, maintain acid-base levels, and help control blood pressure and red blood cell production. Kidney cancer happens when cells in the kidney grow out of control. Most adult cases are Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), which starts in the lining of the kidney’s tubules. RCC has a distinct metabolism, relies heavily on forming new blood vessels, and can behave in many ways, from slow growth to spreading quickly.

Today, doctors see kidney cancer as a group of different diseases that start in the same organ. Instead of just looking at how the cells appear under a microscope, experts now focus on the genetic changes that cause these cancers. This is important because the kidney has many types of cells, and cancer can start in different parts, each with its own outlook and treatment options. The most common type, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, begins in the proximal tubule and is usually caused by changes in the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene. This change makes the tumor act as if it is low on oxygen, pushing it to create new blood vessels to support its growth.

Kidney cancer is closely tied to the organ’s high energy needs. The kidneys get about 20% of the heart’s output to support their work. When cancer develops, the cells change how they make energy, switching from using oxygen efficiently to relying more on glycolysis and making fats. This causes fat and glycogen to build up inside the cells, giving clear cell cancer its typical look. This change helps the tumor survive and grow, even making the environment less friendly to normal cells and the immune system.

Kidney cancer is not limited to tumors in the kidney’s main tissue. It also includes Urothelial Carcinoma, which starts in the lining of the kidney’s drainage system and is more like bladder cancer than other kidney cancers. Rare types, like collecting duct carcinoma and renal medullary carcinoma, are aggressive and start deep in the kidney. Understanding kidney cancer today means knowing about kidney development, blood supply, and the immune system, and seeing the patient as someone facing a complex local crisis in the kidney.

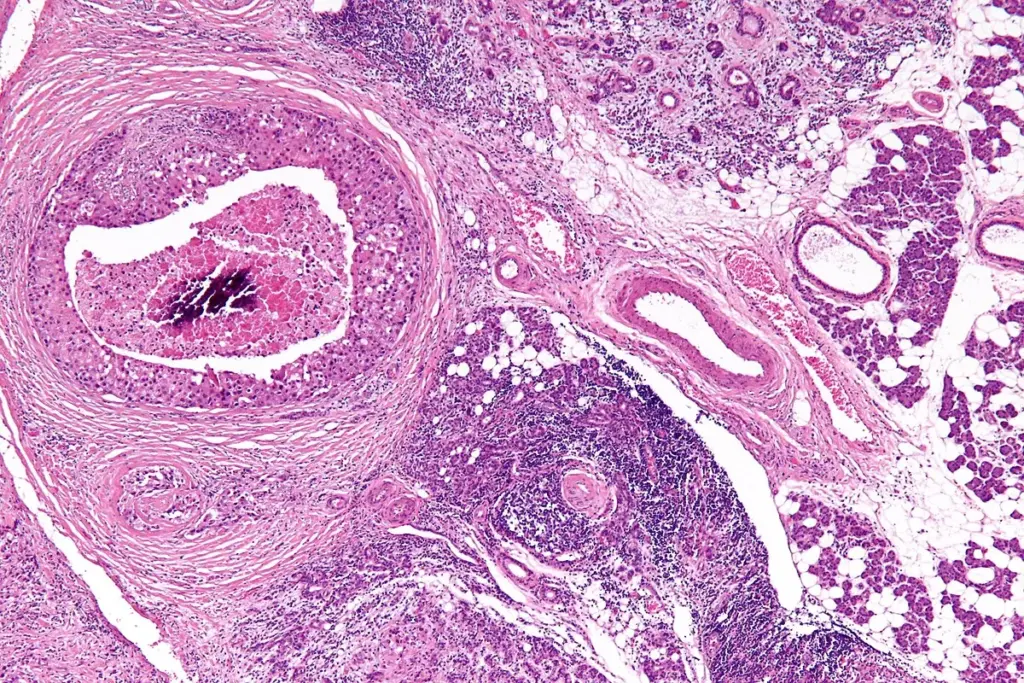

The cellular origin of renal malignancies dictates their biological behavior and their response to systemic therapy. The dominant subtype, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, provides the clearest example of how a specific genetic defect dictates cellular architecture. The loss of the VHL protein function leads to the accumulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIFs). These transcription factors accumulate in the nucleus and drive the expression of genes that promote cell survival, glucose uptake, and, most notably, angiogenesis. Consequently, these tumors are among the most vascularized malignancies in the human body, creating a chaotic network of leaky, immature blood vessels. This hypervascularity is a defining feature that has made kidney cancer the prototype for anti-angiogenic targeted therapies.

Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma, the second most common subtype, presents a different cellular architecture. These tumors typically possess a frond-like growth pattern and are frequently associated with mutations in the MET proto-oncogene or the fumarate hydratase gene. Unlike the lipid-rich clear cells, papillary tumors often exhibit distinct mitochondrial anomalies and a propensity for multifocality, meaning multiple tumors may arise simultaneously within the same kidney. Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma represents another distinct lineage, likely originating from the intercalated cells of the collecting duct. These cells are characterized by an abundance of mitochondria and a unique genetic profile involving the loss of multiple whole chromosomes, which generally confers a more favorable prognosis than the clear cell and papillary variants.

Molecular Subtypes and Genomic Drivers

The kidney is a metabolically active organ, second only to the heart in mitochondrial density and oxygen consumption. Kidney cancer represents a fundamental dysregulation of this metabolic machinery. Malignant renal cells exhibit the Warburg Effect, a phenomenon in which cells preferentially use glycolysis for energy production even in the presence of ample oxygen. This inefficient method of energy generation allows the cancer cells to divert carbon chains into biosynthetic pathways, facilitating the rapid production of lipids, nucleotides, and amino acids required for cell division. This metabolic rewiring is supported by the upregulation of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes, often driven by the same HIF pathways that promote angiogenesis.

This metabolic shift has profound implications for the local microenvironment. The high rate of glycolysis leads to the production and export of lactic acid, creating an acidic extracellular environment. This acidosis suppresses the function of local immune cells, such as T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, thereby creating an immunological shield around the tumor. Furthermore, the accumulation of lipids within the cancer cells serves as a reservoir of energy and building blocks for cell membranes, supporting the tumor’s resilience during periods of nutrient scarcity. Research into “metabolic checkpoints” seeks to exploit these specific vulnerabilities, aiming to starve the cancer by blocking its preferred fuel sources or disrupting its waste disposal mechanisms.

Key Physiological Functions Compromised

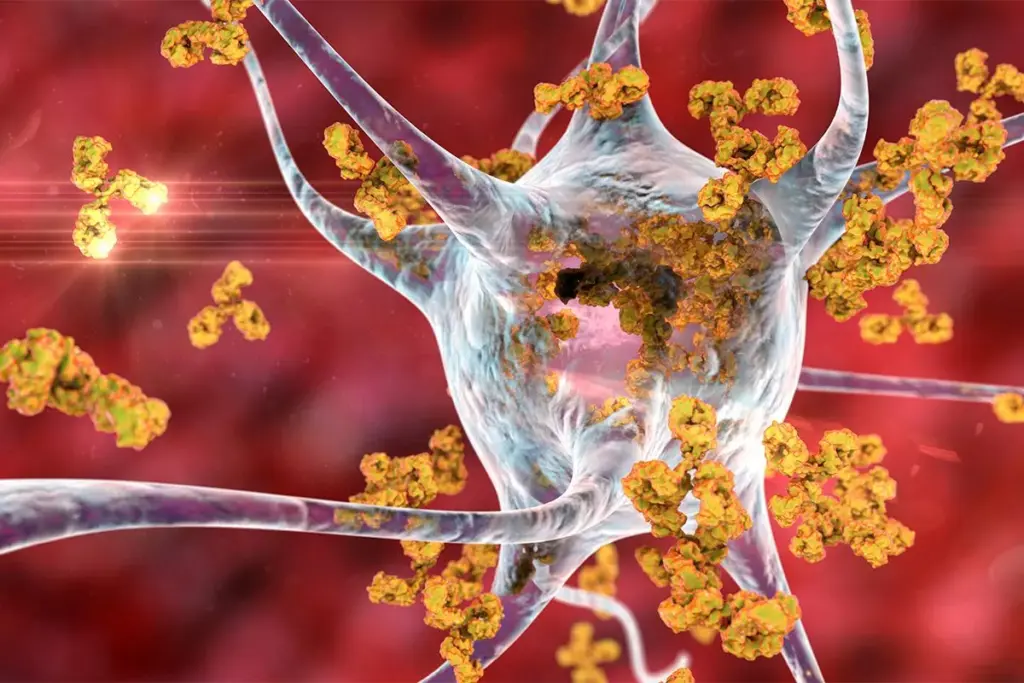

The field of nephro-oncology is currently witnessing a renaissance driven by global advances in biotechnology. The era of “one size fits all” has been replaced by the age of precision medicine, which has replaced cytokine therapy. Modern biotechnology focuses on integrating immunotherapeutics and targeted molecular inhibitors. The realization that kidney tumors are highly immunogenic—meaning they can elicit an immune response—has revolutionized treatment. Biotechnological research has elucidated the mechanisms of immune checkpoints, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, which tumors use to deactivate T-cells. By engineering monoclonal antibodies to block these checkpoints, clinicians can re-engage the patient’s own immune system to recognize and destroy renal cancer cells.

Furthermore, the concept of the “liquid biopsy” is rapidly gaining traction in the global research community. This technology involves isolating and analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from a simple blood draw. This non-invasive method promises to revolutionize the definition of disease status, allowing for the detection of molecular recurrence long before it becomes visible on radiographic imaging. It also provides a dynamic window into the tumor’s evolving genetic landscape, enabling clinicians to identify the emergence of resistance mutations in real time and adjust therapeutic strategies accordingly. The integration of artificial intelligence into the analysis of radiological images, a field known as radiomics, further refines the definition of the disease by predicting tumor aggressiveness and genetic subtype based on subtle imaging patterns invisible to the human eye.

In the context of regenerative medicine, the definition of kidney cancer management has expanded to include the preservation of renal function. The kidney possesses a limited capacity for regeneration; once nephrons are lost, they are not replaced. Therefore, the modern approach to kidney cancer emphasizes “nephron-sparing” procedures. This philosophy dictates that, whenever oncologically safe, the tumor should be removed while preserving the remaining healthy kidney tissue. This is critical because chronic kidney disease is a significant long-term risk factor for cardiovascular mortality.

Robotic-assisted surgical platforms represent a technological pinnacle in this domain, enabling precise tumor excision and rapid reconstruction of the renal defect to minimize ischemia time (the time the kidney is without blood flow). Concurrently, research into renal stem cells and bioscaffolds aims to enhance kidney healing after partial resection, minimizing scar formation and maximizing functional recovery. The intersection of oncology and nephrology thus strives for a dual goal: the complete eradication of the malignancy and the maximal conservation of the patient’s renal reserve.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

A renal cyst is a fluid-filled sac that is very common and usually benign, posing no threat to health. Kidney cancer is a solid tumor composed of malignant cells that grow uncontrollably. Radiologists use specific imaging criteria, such as the Bosniak classification, to distinguish between harmless simple cysts and complex cysts or solid masses that require surgical intervention.

Primary kidney cancer originates within the kidney tissues, but the kidney can also be a site for metastases from other cancers, such as lymphoma or lung cancer. Additionally, cancers can arise in the renal pelvis, which collects urine; these are urothelial carcinomas and are biologically similar to bladder cancer, requiring different treatments than the more common renal cell carcinoma found in the kidney parenchyma.

The kidneys are located deep within the body in the retroperitoneal space, allowing tumors to grow quite large without causing a visible lump or pain. Because the other kidney can compensate for the loss of function, symptoms like kidney failure are rare in the early stages. Consequently, many tumors are discovered incidentally during scans for unrelated issues.

Most kidney cancers are sporadic, meaning they occur by chance due to mutations acquired during life. However, about three to five percent of cases are part of hereditary syndromes, such as Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, or Hereditary Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. These conditions often lead to multiple tumors in both kidneys and require specialized genetic screening and management.

The VHL gene is a tumor suppressor gene that acts as a gatekeeper for cell growth and oxygen sensing. In the majority of clear cell renal cell carcinomas, this gene is mutated or silenced, leading the cells to falsely believe they are oxygen-starved falsely falsely. This triggers the formation of new blood vessels and rapid cell growth, resulting in a highly vascular tumor.

The ICD-10 code Z94.89 is key for patients who have had organ and tissue transplants. At livhospital.com, we know how important accurate coding is for

Recent studies have shown that PET scans are safe for patients, even those with kidney disease. The FDG tracer in PET scans is not harmful

Kidney disease is a big problem in the United States. Over 37 million adults have some form of kidney disease, says the National Kidney Foundation.

For patients with renal cell carcinoma, surgery is often the main treatment. At Liv Hospital, we use our medical skills and care to help patients

Surgery is often the first choice for treating kidney tumors that are in one place. At Liv Hospital, we know how important renal cell carcinoma

At Liv Hospital, we know how important it is to look into other treatments for kidney cancer. While supplements can’t cure cancer on their own,

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)