Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Pediatric oncology is a unique branch of medicine that differs from adult oncology in several key ways, including the origins and biology of the cancers. Adult cancers often develop over time due to environmental exposures and aging, leading to carcinomas. In contrast, most pediatric cancers are related to problems in early development. These cancers start when the normal process of organ and cell development goes wrong, causing immature cells to keep dividing instead of maturing into their proper roles. Understanding this difference is crucial for how we diagnose, treat, and manage cancer in children.

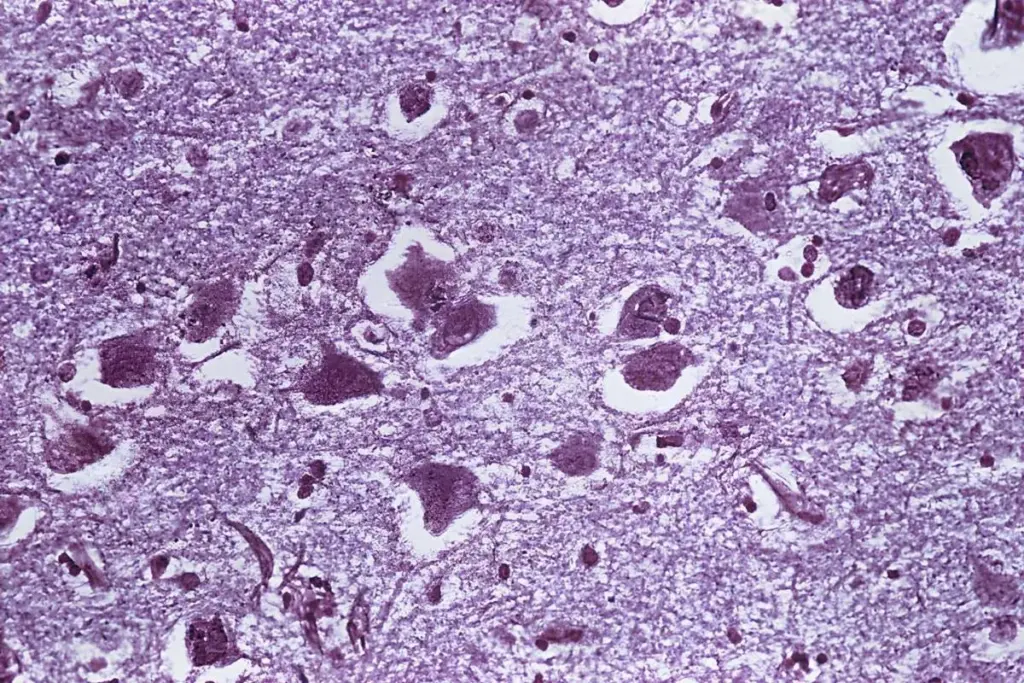

Pediatric cancers often look more like fetal tissue than adult tissue under the microscope. Many are called small, round, blue cell tumors because of their appearance, which shows they are made of immature cells. These tumors grow quickly, unlike most adult cancers, because the signals that should stop cell growth after birth stay active. While this fast growth makes the disease aggressive, it also means these cancers respond well to treatments that target dividing cells, which helps explain why cure rates in children are often higher than in adults.

Pediatric cancers have a different genetic profile compared to adult cancers. Adult tumors usually have many mutations built up over years, but childhood cancers often have only a few key genetic changes. These changes, like chromosomal translocations or gene amplifications (for example, MYCN), act as strong triggers that keep cells growing. Because of this, doctors can use more precise molecular tests to diagnose and plan treatment for pediatric cancers, rather than relying only on where the tumor is in the body.

The pathogenesis of many pediatric cancers is rooted in the concept of developmental arrest. During embryogenesis, pluripotent stem cells differentiate through a hierarchy of progenitors to form specific organs. In pediatric oncology, a specific progenitor cell often sustains a genetic hit that prevents it from completing this differentiation program. The cell remains stuck in a proliferative, embryonic stage, expanding clonally to form a tumor. For instance, Wilms tumor represents a failure of the nephrogenic blastema to differentiate into renal tubules and glomeruli, while retinoblastoma results from the arrest of retinal progenitor differentiation.

This way of thinking changes the focus from just removing the tumor to understanding why the cells stopped maturing. Treatments like regenerative medicine and differentiation therapy try to help these cancer cells finish developing into normal, healthy cells. This approach shows that pediatric oncology is as much about understanding development as it is about treating cancer.

The genomic architecture of pediatric cancer is characterized by specific, recurrent structural variations rather than the point mutations common in adults. Chromosomal translocations, where parts of two chromosomes break and fuse, create novel fusion proteins that function as potent oncogenes. These fusion oncoproteins act as master regulators, reprogramming the cell’s transcriptional machinery to maintain a stem-cell-like state. The EWS-FLI1 fusion in Ewing Sarcoma is a prototypical example in which the fusion protein aberrantly activates targets that drive cell proliferation and survival.

Furthermore, the role of germline predisposition is significantly more pronounced in the pediatric population. It is estimated that at least ten percent of children with cancer have an underlying cancer predisposition syndrome, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. These syndromes involve germline mutations in critical tumor-suppressor genes, such as TP53, or growth-regulatory genes. Understanding this germline context is essential not only for treating the index patient but also for patient surveillance and surveillance of the patient’s family members.

Pediatric cancer affects the whole body of a growing child. Unlike adult cancer care, which often focuses on saving what organ function remains, pediatric oncology must consider how both the disease and its treatment affect the child’s ongoing growth and development. Fast-growing tissues like bone marrow, growth plates, and the developing brain are especially at risk.

Cancer itself can cause changes throughout a child’s body. For example, leukemia can damage the bone marrow, leading to anemia and a weak immune system even before any treatment starts. Some solid tumors release hormones or other substances that affect growth and metabolism. As a result, a child with cancer has high nutritional needs, but the tumor also uses up energy, making it harder for the child to grow normally.

The management of pediatric cancer is at the forefront of global biotechnology, particularly in the realms of immunotherapy and precision medicine. The field has moved beyond the era of non-specific chemotherapy to the era of targeted cellular engineering. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in which the patient’s own immune cells are genetically modified ex vivo to express a receptor that recognizes a specific antigen on leukemia cells. This “living drug” has revolutionized the treatment of refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Concurrently, the integration of next-generation sequencing into routine clinical care enables molecular profiling of every tumor. This “precision oncology” approach seeks to match specific genomic alterations with targeted inhibitors, regardless of the histological tumor type. Liquid biopsies, which detect circulating tumor DNA in the blood, are emerging as non-invasive tools for monitoring treatment response and detecting relapse earlier than radiographic imaging.

The classification of pediatric cancers is distinct from that of adults, dominated by leukemias, brain tumors, and sarcomas rather than epithelial carcinomas. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy, originating from lymphocyte precursors. Central nervous system tumors form the second largest group, ranging from low-grade gliomas to highly aggressive medulloblastomas. Extracranial solid tumors include neuroblastoma (sympathetic nervous system), Wilms tumor (kidney), rhabdomyosarcoma (muscle), and osteosarcoma (bone).

Each of these categories is further subdivided based on histology and molecular features. For example, medulloblastoma is no longer treated as a single entity. Still, it is stratified into four distinct molecular subgroups (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4), each with a different prognosis and treatment protocol. This granular classification ensures that therapy is tailored to the tumor’s specific biology, maximizing cure rates while minimizing toxicity.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Pediatric cancers are primarily embryonal or developmental in origin, arising from primitive cells that fail to mature. In contrast, adult cancers are typically carcinomas arising from epithelial tissues, driven by cumulative environmental damage and aging. This biological difference means pediatric cancers often grow faster but are more responsive to chemotherapy.

This term describes the microscopic appearance of many pediatric cancers, such as neuroblastoma and lymphoma. These cells appear this way because they are primitive, undifferentiated cells with large nuclei and minimal cytoplasm, reflecting their embryonic nature and rapid rate of division.

A germline mutation is a genetic alteration present in the egg or sperm that is passed down to the child and exists in every cell of their body. In pediatric oncology, these mutations predispose the child to developing cancer, as seen in syndromes like Li-Fraumeni or Retinoblastoma, unlike somatic mutations, which occur only in the tumor cells.

Developmental arrest occurs when a primitive stem or progenitor cell becomes stuck at an immature stage and continues to divide rather than maturing into a functional cell. This population of immature, dividing cells accumulates to form a tumor, which is the underlying mechanism in many pediatric malignancies, such as Wilms’ tumor.

Fusion oncogenes form when parts of two chromosomes break and fuse, a process standard in pediatric cancers such as Ewing Sarcoma. These fusion genes produce abnormal proteins that act as powerful drivers of cancer cell growth and serve as specific targets for diagnosis and, potentially, new therapies.

Knowing what a polyp is is key to understanding colorectal cancer risk. A polyp is a growth inside the colon or rectum. Most are harmless,

Are polyps scary in kids? Discover amazing facts about childhood health and find powerful ways to protect your family’s vital digestion. Polyps in the gut

Getting a cancer diagnosis can feel like a lot to handle. But, it’s key to take the right steps for the best treatment. Research indicates

Many think cancer leads to unintentional weight loss. But, some cancers cause weight gain. Obesity-related cancers, like breast cancer and endometrial cancer, are often linked

Nuclear medicine is key in finding and treating childhood diseases. Pediatric nuclear medicine is common and used often in kids’ care. Every year, almost 370,000

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)