Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

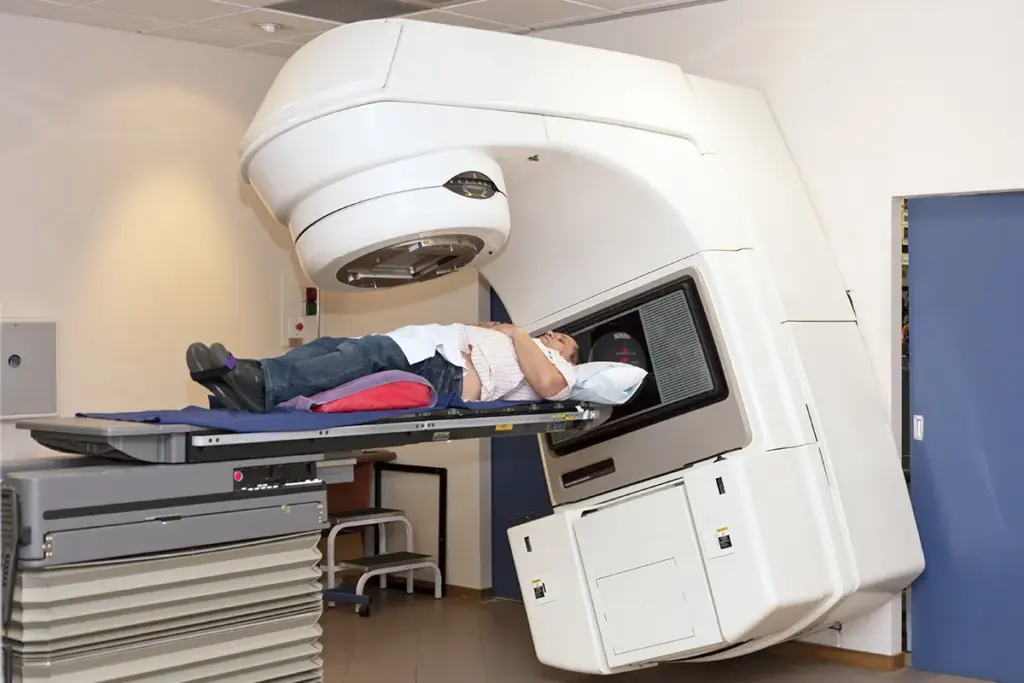

Radiation therapy, also called RT or XRT, is one of the main treatments for cancer, along with surgery and chemotherapy. It involves carefully using ionizing radiation on body tissues to destroy cancer cells. This treatment uses high-energy particles or waves, such as x-rays, gamma rays, electron beams, or protons, to damage the DNA of cancer cells. The main goal is to stop the tumor from growing and dividing, while protecting the nearby healthy tissues as much as possible.

At the cellular level, radiation therapy works by breaking the chemical bonds in DNA. This can happen directly, when radiation hits the DNA, or indirectly, when radiation creates free radicals from water in the cell that then damage the DNA. If a cell with damaged DNA tries to divide, it cannot do so properly and dies. Cancer cells are especially sensitive to this process because they divide quickly and often cannot repair their DNA as well as normal cells.

From the perspective of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, radiation therapy is a potent modulator of the local microenvironment. While its primary intent is destructive towards the malignancy, it also initiates a cascade of cytokine releases and vascular changes that alter the landscape of the treated tissue. Modern radiation oncology is no longer a “one-size-fits-all” approach but a highly personalized discipline. It has evolved from 2D planning based on simple X-rays to 4D treatment planning that accounts for the physiological motion of organs, such as breathing or digestion. The definition of radiation therapy now encompasses a spectrum of techniques ranging from curative intent, where high doses are delivered to eliminate the tumor, to palliative intent, where lower doses are used to relieve symptoms like pain or bleeding, and even to stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR), which delivers surgical-like precision without an incision.

The principles of radiobiology govern the clinical application of radiation, specifically the “Four Rs”: Repair, Reassortment, Repopulation, and Reoxygenation. These principles dictate why radiation is typically delivered in daily small doses, called fractions, over several weeks rather than in a single massive dose.

Reoxygenation: Hypoxic (oxygen-starved) tumor cells are resistant to radiation. As the outer layers of a tumor are killed, oxygen can penetrate deeper, making the remaining core cells more sensitive to subsequent doses.

Biotechnology and artificial intelligence are now key parts of radiation oncology. Modern linear accelerators (LINACs) can shape the radiation beam very precisely using small tungsten leaves that move during treatment. Some machines now combine MRI with the LINAC, allowing doctors to adjust the treatment plan each day based on changes in the tumor or organs. This approach keeps the treatment focused on the right spot throughout therapy.

Modern radiation therapy aims to protect the body’s ability to heal by reducing damage to healthy tissues. Radiation can harm important stem cell areas in organs like the salivary glands, bone marrow, and the hippocampus. Advanced methods like IMRT and VMAT help shape the radiation dose to avoid these areas. By doing this, doctors try to keep organs working well and maintain the patient’s quality of life after treatment.

Key Physiological Mechanisms Utilized

Fibrosis Induction: In the healing phase, radiation induces collagen deposition, which can wall off residual tumor cells but also impairs tissue flexibility.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

External beam radiation delivers high-energy rays from a machine (a linear accelerator) outside the body, aiming them at the tumor from various angles. Brachytherapy, or internal radiation, involves placing radioactive sources (seeds, ribbons, or capsules) directly inside or next to the tumor, allowing for a higher dose to the cancer with less exposure to surrounding healthy tissues.

Patients undergoing external beam radiation do not become radioactive. The radiation ends the moment the machine is turned off, and it is safe for them to be around others, including children and pregnant women. However, patients receiving systemic radioisotopes or permanent brachytherapy implants may emit low levels of radiation for a short time and require specific safety precautions.

Chemotherapy is a systemic treatment that uses drugs traveling through the bloodstream to kill rapidly dividing cells throughout the entire body. Radiation therapy is a local treatment that affects only the specific part of the body where the beam is aimed. Therefore, radiation side effects are generally limited to the treated area, whereas chemotherapy side effects are systemic.

The Gray (Gy) is the unit of absorbed radiation dose. One Gray is defined as the absorption of one joule of radiation energy per kilogram of matter. Oncologists prescribe the total dose in Grays (e.g., 60 Gy) and divide it into smaller daily fractions (e.g., 2 Gy per day) to maximize tumor kill while sparing normal tissue.

The actual delivery of external beam radiation is painless, similar to having an X-ray taken. Patients do not feel, see, or smell the radiation as it enters the body. However, side effects that develop over time, such as skin irritation (e.g., sunburn) or inflammation of internal linings (mucositis), can cause discomfort and pain as the treatment progresses.

Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer Cancer

Cancer

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)