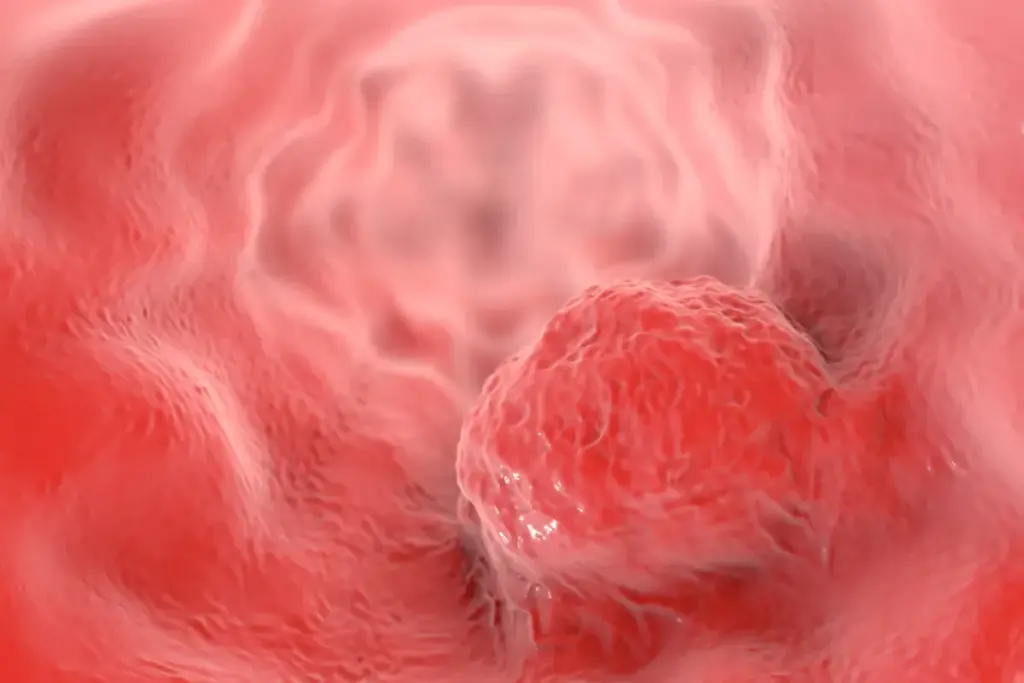

Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

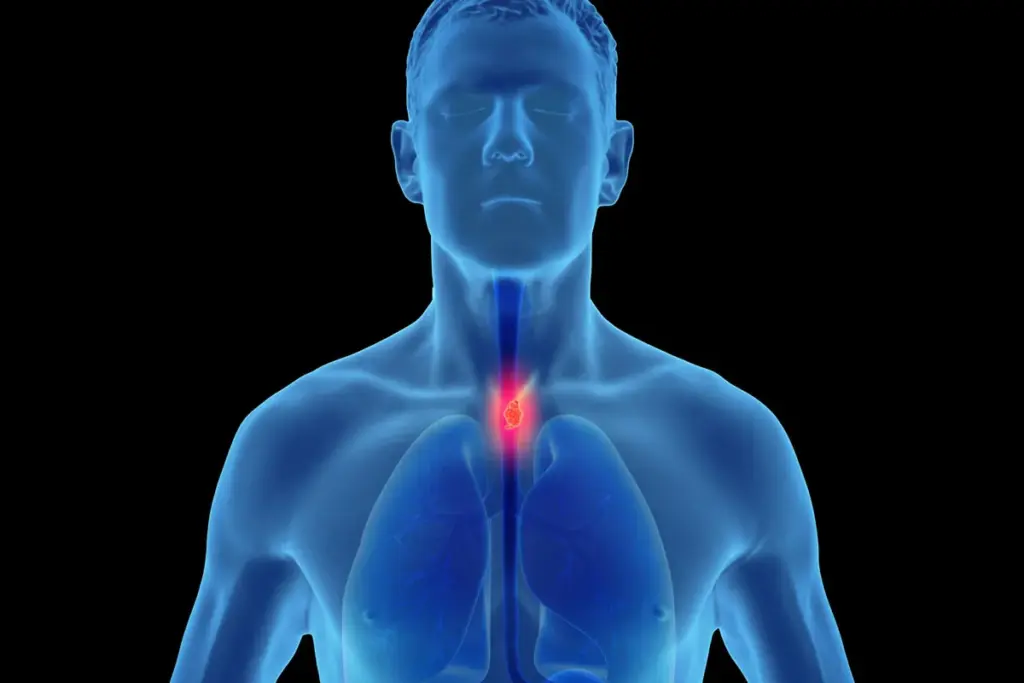

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the throat to the stomach, helping move food quickly and efficiently. Esophageal cancer happens when the cells lining this tube become cancerous, often spreading early because the esophagus lacks a protective outer layer. There are two main types of esophageal cancer: Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma. Although both start in the esophagus, they differ in how common they are, what causes them, and the types of cells they come from. Understanding these differences is important for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma starts in the flat cells lining the upper and middle parts of the esophagus and is often linked to long-term irritation, making it the most common type worldwide. Esophageal Adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, begins in glandular cells near the lower esophagus, usually where it meets the stomach. This type is closely related to chronic acid reflux and Barrett’s esophagus, a condition where the normal lining changes to protect against acid but becomes unstable. Today, esophageal cancer is defined not just by where it starts, but also by the underlying changes in the cells and their environment.

The lining of the esophagus is constantly renewing itself, thanks to stem cells at its base. Cancer develops when this renewal process goes wrong. In Adenocarcinoma, long-term exposure to acid and bile causes these stem cells to change into a different, less stable cell type, which can become cancerous. In Squamous Cell Carcinoma, damage to the stem cells leads to DNA changes and loss of normal cell control. As a result, esophageal cancer is now seen as a problem where the body’s repair system becomes disrupted and leads to cancer.

The structure of the esophagus affects how cancer behaves. Normally, the esophagus is lined with tough, flat cells that protect it from food. Squamous Cell Carcinoma keeps some of these features but loses normal cell organization and invades deeper layers. This type of cancer often has a lot of inflammation and low oxygen areas, which encourage the growth of new blood vessels.

Adenocarcinoma forms in a changed environment, often after Barrett’s esophagus develops. In Barrett’s, the lining changes to include mucus-producing cells, which can become cancerous and form glands that grow into deeper layers. The esophagus has many lymph vessels close to its surface, unlike the colon. This makes it easier for even small tumors to spread to nearby lymph nodes, which is why this cancer can be so aggressive.

Molecular Pathogenesis and Genomic Drivers

Esophageal cancer rates vary widely by region and population. Squamous Cell Carcinoma is most common along the so-called Asian Esophageal Cancer Belt, from the Middle East to China, mainly due to diet and environment. In contrast, Western countries have seen a sharp increase in Adenocarcinoma over the past 40 years, which is linked to rising obesity and more cases of chronic acid reflux.

Because of this change, Western medicine now focuses more on monitoring people with Barrett’s esophagus. Doctors use targeted screening to find those at risk and catch the disease before it turns into cancer. This approach is based on the fact that Adenocarcinoma usually develops in steps: first inflammation, then cell changes, then abnormal growth, and finally cancer. Stopping the process early is the main goal of prevention.

Metaplasia is key to understanding Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. It happens when one type of mature cell changes into another type that can better handle stress. In the esophagus, the usual flat cells are replaced by columnar cells that resist acid. While this change helps at first, these new cells are unstable and more likely to develop mutations.

Scientists are studying how cells in the esophagus change and what controls these changes. Proteins like CDX2 help drive the switch to intestinal-type cells seen in Barrett’s esophagus. By learning more about these processes, researchers hope to find treatments that can reverse these changes or stop them from becoming cancer, helping the esophagus heal normally.

Key Physiological Functions Compromised

The management of esophageal cancer is increasingly driven by bio-intelligent pathways that integrate genomic data with clinical staging. The definition of resectability has evolved. It is no longer just about anatomical location, but also about biological behavior. Patients are stratified not only by TNM stage but also by their physiological reserve and tumor molecular profile.

Modern definitions also incorporate the response to neoadjuvant therapy. Esophageal cancer is rarely treated with surgery alone. The standard of care involves chemotherapy and radiation before resection. The tumor’s response to this initial therapy whether it shrinks significantly or remains stable redefines the prognosis. A “complete pathological response,” where no live tumor cells are found at the time of surgery, is the new benchmark for therapeutic success. This integrates the biological response into the clinical definition of the disease status.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma develops in the flat, thin cells lining the upper and middle esophagus and is often linked to smoking and alcohol. Adenocarcinoma arises from glandular cells in the lower esophagus, usually at the junction with the stomach, and is strongly associated with chronic acid reflux, obesity, and Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s Esophagus is a condition where the usual lining of the esophagus changes to resemble the lining of the intestine. This is a regenerative adaptation to chronic acid exposure from reflux. It is considered a pre-cancerous condition because these altered cells have a higher risk of developing into Esophageal Adenocarcinoma over time.

No, esophageal cancer is not contagious and cannot be spread from person to person. It is caused by genetic mutations within an individual’s cells, driven by a combination of lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, and chronic inflammation, not by a transmissible virus or bacteria.

The esophagus can stretch significantly to accommodate food, so a tumor can grow quite large before it causes difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), which is usually the first noticeable symptom. Because there are few pain receptors in the early mucosal lining, early-stage cancers are often painless and silent, leading to delayed diagnosis.

While chronic reflux (GERD) is a risk factor for Adenocarcinoma, the vast majority of people with reflux never develop cancer. The progression from reflux to Barrett’s esophagus and then to cancer occurs in a small percentage of individuals. However, chronic and severe reflux should be managed medically and monitored by a specialist.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)