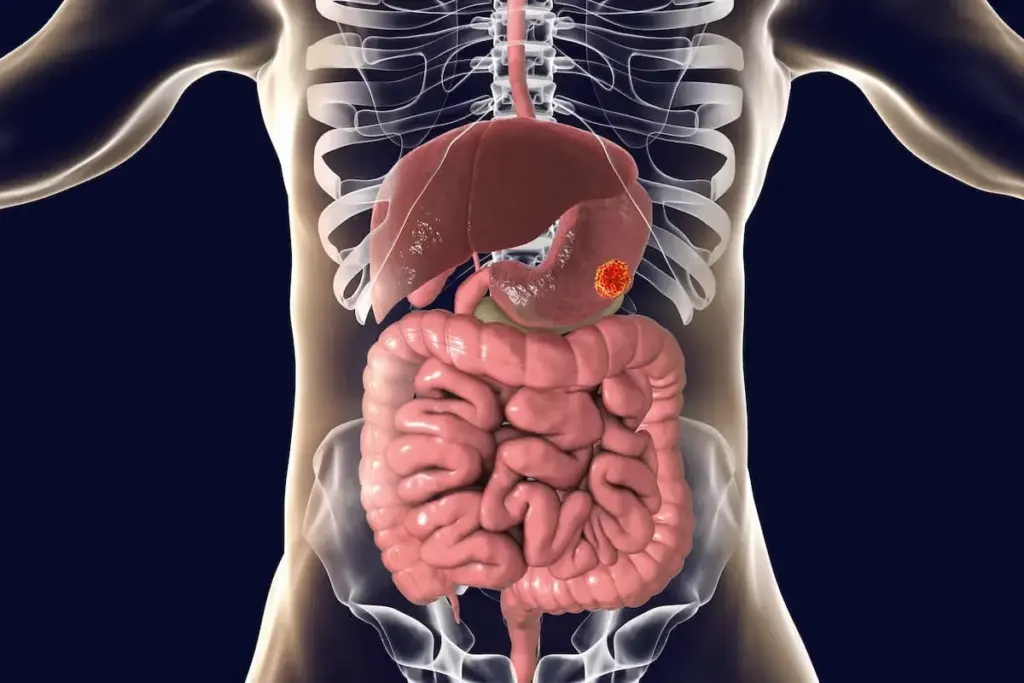

Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

The definitive diagnosis of gastric cancer relies entirely on visual inspection and tissue acquisition, making Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), or upper endoscopy, the gold standard procedure. During an EGD, a flexible tube with a high-definition camera is passed through the mouth into the stomach. This allows the gastroenterologist to examine the entire mucosal surface. Modern endoscopes are equipped with advanced imaging technologies such as Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) or chromoendoscopy. These techniques use specific wavelengths of light or dyes to highlight abnormal blood vessel patterns and subtle mucosal irregularities that might be invisible under standard white light.

Because early gastric cancer can look like a benign ulcer or a patch of redness, the endoscopist must have a high index of suspicion. Any suspicious lesion, and even benign-appearing gastric ulcers, must be biopsied. The standard protocol involves taking multiple tissue samples from the center and the margins of the lesion to avoid missing the cancer cells. These samples are sent to pathology for histological confirmation.

In Japan and South Korea, where incidence is high, population-based endoscopic screening has been implemented, leading to the detection of many cancers at the earliest, most curable stages. In Western nations, screening is not universal but is reserved for high-risk individuals, such as those with a family history, genetic syndromes, or chronic atrophic gastritis. The quality of the endoscopy is paramount; a hurried exam or a stomach not fully cleared of food debris can easily lead to missed diagnoses.

Once a diagnosis of cancer is confirmed via biopsy, the next critical question is “how deep?” This determines the treatment path. Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) is the most accurate tool for answering this. An EUS scope has a miniature ultrasound probe at its tip. By placing this probe directly against the stomach wall, the physician can see the stomach’s layers as distinct bands.

EUS allows for the precise determination of the “T” stage (Tumor depth). It can distinguish between a tumor that is limited to the mucosa (T1a), one that invades the submucosa (T1b), and one that invades the muscle layer (T2) or beyond. This distinction is vital because T1a tumors may be treated endoscopically without surgery, whereas T1b and deeper tumors usually require surgical gastrectomy and lymph node removal.

Furthermore, EUS is excellent for assessing the regional lymph nodes located just outside the stomach wall. Enlarged or round lymph nodes suggest metastatic spread. The EUS scope can also be used to perform a Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) of these nodes to confirm if they contain cancer cells. This information helps oncologists decide if chemotherapy should be given before surgery to shrink the disease.

To evaluate the broader extent of the disease, particularly distant spread, Computed Tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is the standard modality. A high-quality CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast helps visualize the primary tumor, the relationship to major blood vessels, and the presence of metastases in the liver, lungs, or distant lymph nodes. Positron Emission Tomography (PET-CT) is often used as an adjunct, especially for tumors at the gastroesophageal junction, as it relies on the metabolic activity of the tumor cells (their hunger for sugar) to light up areas of active cancer that might look normal on a CT scan.

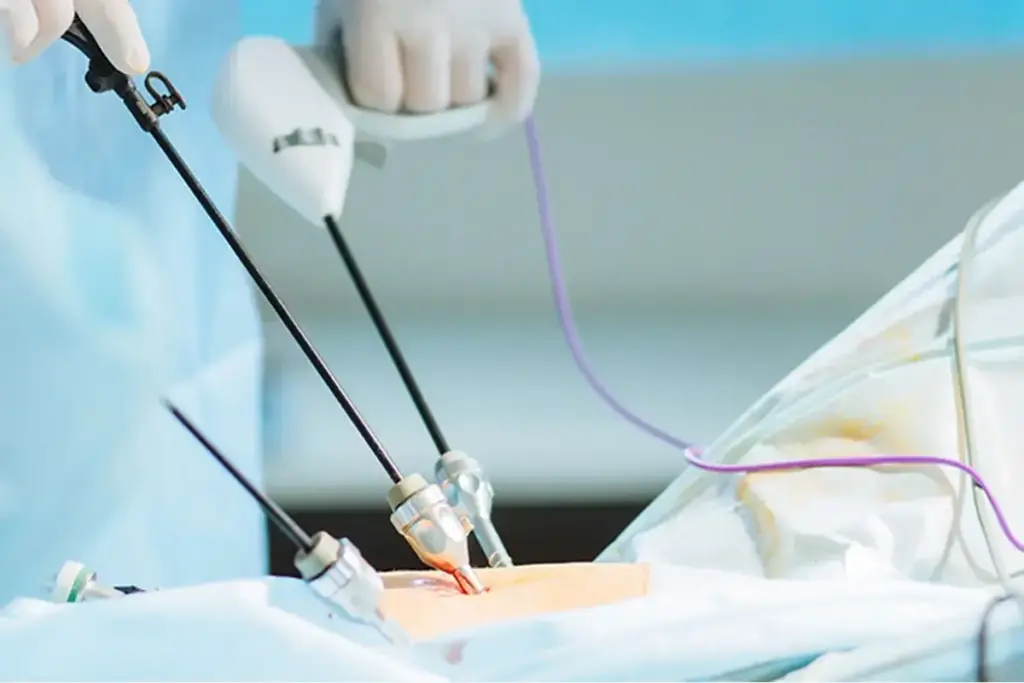

However, gastric cancer has a notorious limitation with CT scans: it often spreads to the peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen) in the form of tiny, sand-like grains that are too small to be seen on any scan. This is called “occult metastatic disease.” To address this, a Staging Laparoscopy is frequently performed for patients with potentially resectable tumors.

In this minimally invasive surgical procedure, a camera is inserted into the abdomen to inspect the liver surface and the peritoneum visually. The surgeon also performs “peritoneal washings,” where saline is poured into the abdomen and then sucked back out. This fluid is analyzed by a pathologist for free-floating cancer cells (positive cytology). If free cells or visible peritoneal seeds are found, the cancer is considered Stage IV (metastatic), and major surgery to remove the stomach is usually aborted in favor of systemic chemotherapy, sparing the patient a futile and debilitating operation.

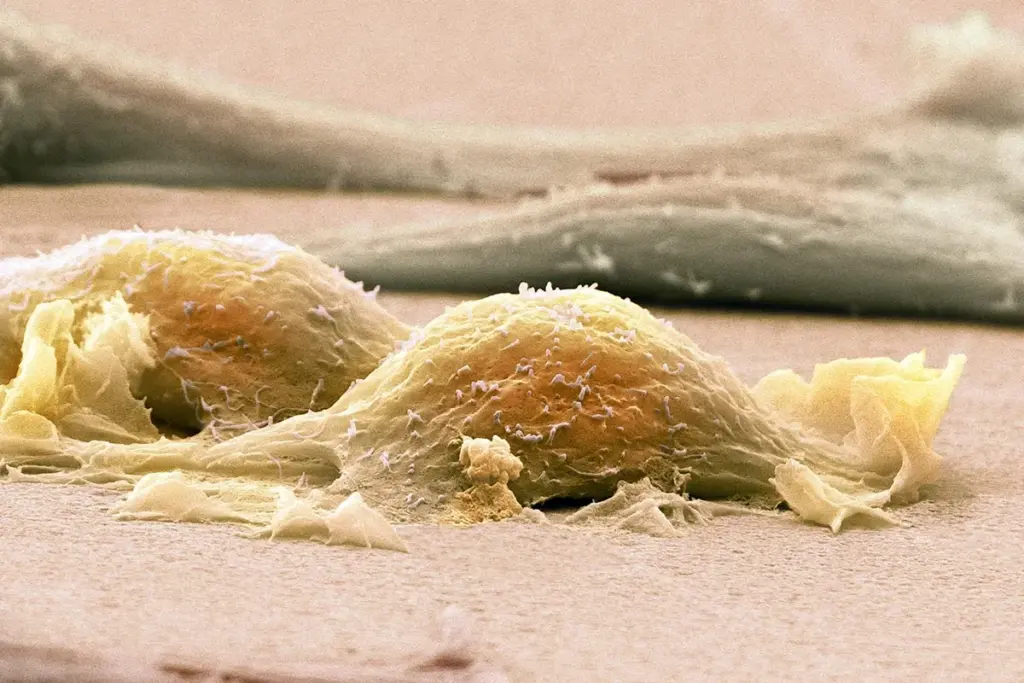

The diagnosis is not complete until the tumor’s molecular profile is understood. Modern pathology goes beyond just saying “adenocarcinoma.” The biopsy tissue is tested for specific biomarkers that serve as targets for biological therapies. The most critical biomarker is HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2). Overexpression of HER2 occurs in about twenty percent of gastric cancers, particularly intestinal types. Identifying this allows for the use of trastuzumab, a drug that targets this receptor.

Another crucial test is for Microsatellite Instability (MSI) or Mismatch Repair Deficiency (dMMR). Tumors that are MSI-High have a high mutation burden because they cannot repair DNA damage. Paradoxically, these tumors often have a better prognosis and respond exceptionally well to immunotherapy (checkpoint inhibitors) but may not respond as well to standard chemotherapy.

Testing for PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1) expression is also standard. This protein helps cancer cells hide from the immune system. The level of PD-L1 expression helps predict the efficacy of immunotherapy drugs. In some cases, testing for EBV (Epstein-Barr Virus) is performed, as EBV-positive tumors form a distinct subgroup that may be more sensitive to immunotherapy. This transition from histological to molecular staging is the foundation of personalized oncology.

The prognosis and treatment plan are formalized using the TNM classification system.

T (Tumor): Describes how deeply the primary tumor has grown into the stomach wall. T1 is superficial, T2 invades muscle, T3 invades the subserosa, and T4 invades the serosa or adjacent organs.

N (Node): Describes the number of regional lymph nodes containing cancer. N0 is none, N1 is 1-2 nodes, N2 is 3-6, and N3 is seven or more. The number of positive nodes is a powerful predictor of survival.

M (Metastasis): Indicates whether the cancer has spread to distant organs (liver, lungs, peritoneum) or distant lymph nodes. M0 is no spread, M1 is distant spread.

These components are grouped into stages 0 through IV. Stage I is early and highly curable. Stages II and III are locally advanced but potentially curable with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy. Stage IV represents metastatic disease, where the goal is typically palliative—extending life and controlling symptoms—rather than cure. Accurate staging is a dynamic process and may change after surgery when the pathologist examines the whole specimen (pathological staging vs. clinical staging).

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Clinical stage is the doctor’s best estimate of the cancer’s extent based on CT scans, EUS, and physical exam before any treatment starts. Pathological stage is determined after surgery, when the pathologist examines the tumor and lymph nodes under a microscope. The pathological stage is more accurate and determines the need for further treatment.

CT scans are excellent for seeing large masses, but they are inferior at seeing tiny spots of cancer (less than 5mm) on the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum). A laparoscopy allows the surgeon to see these tiny spots directly. Finding them changes the treatment from surgery to chemotherapy, saving you from an unnecessary major operation.

Being HER2-positive means your cancer cells have too many copies of a gene that makes a growth-promoting protein called HER2. This drives the cancer’s growth. However, it is also a target. Drugs like trastuzumab can attach to this protein and shut it down, which is a very effective treatment option not available to HER2-negative patients.

No. The risk of spreading gastric cancer through a standard endoscopic biopsy is virtually non-existent. The biopsy forceps take tiny samples from the inside of the stomach. The benefits of obtaining a diagnosis to plan life-saving treatment vastly outweigh any theoretical risks.

Generally, no. While markers like CEA and CA 19-9 can be elevated in stomach cancer, they are not specific and can be normal even in advanced disease. Newer tests looking for circulating tumor DNA are being developed, but currently, a diagnosis always requires an endoscopy and biopsy.

Medical imaging tests, like CT scans, use contrast agents to make internal structures clearer. These substances are usually safe but can upset some people’s stomachs.

Can stomach cancer cause itchy skin? Many people are unaware that stomach cancer can present in unusual ways.. One of these is itchy skin. This

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)