Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

For a fortunate subset of patients diagnosed at the very earliest stage (T1a), organ-preserving treatment is possible. Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) and Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) are minimally invasive techniques performed through the mouth, without any external incisions. These procedures are feasible only when the risk of lymph node metastasis is negligible—typically in small, non-ulcerated tumors confined strictly to the mucosa.

ESD is the more advanced technique. It involves injecting a fluid cushion under the tumor to lift it away from the muscle layer. Then, using specialized electrosurgical knives passed through the endoscope, the physician carves around and underneath the tumor, removing it in one single piece (en bloc). This allows the pathologist to examine the edges and confirm that the cancer is completely removed.

If the pathology report shows the cancer was deeper than expected or had aggressive features, surgery may still be recommended. However, in successful cases, ESD offers a cure while preserving the stomach, maintaining the patient’s quality of life and nutritional status. This approach is standard in Japan and is becoming increasingly available in specialized Western centers.

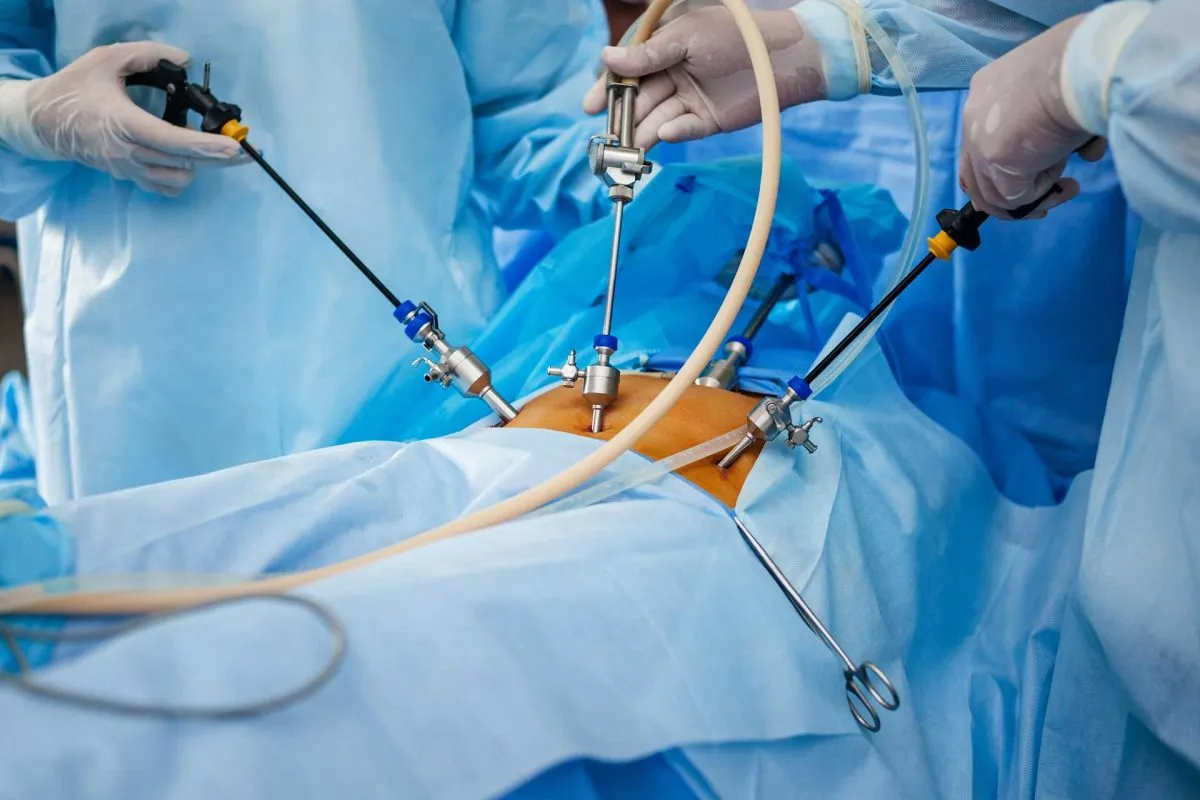

For cancers that have invaded beyond the mucosa but are not metastatic, the cornerstone of curative treatment is radical gastrectomy. The extent of the resection depends on the tumor’s location. For tumors in the lower part of the stomach (antrum), a Subtotal Gastrectomy is performed, removing the lower two-thirds of the stomach. For tumors in the body or upper part of the stomach, a Total Gastrectomy is required, removing the entire organ.

The critical component of cancer surgery is not just removing the stomach, but reconstructing the digestive tract. In a subtotal gastrectomy, the small intestine is connected to the stomach remnant (Billroth II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction). In a total gastrectomy, the esophagus is connected directly to the small intestine (Esophagojejunostomy). The Roux-en-Y reconstruction is the preferred method as it prevents bile from the liver from refluxing into the esophagus, which can cause severe pain and inflammation.

Oncological safety demands obtaining “negative margins,” meaning no cancer cells are found at the cut edges of the tissue. If cancer cells are found at the margin (R1 resection), the risk of recurrence is high. Therefore, surgeons often remove a significant cuff of healthy tissue around the tumor to ensure complete clearance.

Removing the stomach addresses the primary tumor, but addressing the lymph nodes is equally vital to prevent local recurrence. The extent of lymph node removal is a subject of global debate but has standardized over time. A “D1” dissection removes only the nodes attached directly to the stomach. A “D2” dissection removes the D1 nodes plus the nodes along the major arteries feeding the stomach (hepatic, splenic, celiac, and left gastric arteries).

Decades of clinical trials have established the D2 lymphadenectomy as the standard of care for curative intent. While it is a more technically demanding surgery with a slightly higher risk of complications, it provides better long-term survival rates by removing microscopic deposits of cancer that D1 surgery would leave behind. Current guidelines recommend retrieving 15-25 lymph nodes to achieve accurate staging, though D2 dissections often yield many more.

In some cases, adjacent organs must be removed to achieve a complete clearance. For instance, the spleen may be removed (splenectomy) if the cancer is invading the splenic hilum. However, surgeons try to preserve the spleen whenever possible to maintain the patient’s immune function.

Surgery alone is often insufficient for locally advanced gastric cancer (Stage II and III) because microscopic cells may have already spread into the bloodstream. Therefore, the standard of care in the West has shifted to “perioperative chemotherapy.” This involves administering chemotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant) and continuing it after surgery (adjuvant).

The current gold standard regimen is known as FLOT (Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, Oxaliplatin, and Docetaxel). Administering chemotherapy before surgery has several advantages: it shrinks the tumor, increasing the chance of a successful surgical removal; it treats potential micrometastases early; and it acts as an “in vivo” test of whether the cancer is sensitive to the drugs. Patients typically receive four cycles of FLOT, undergo surgery, and then receive four more cycles.

For patients who are not candidates for the aggressive FLOT regimen due to age or frailty, other combinations like FOLFOX or CAPOX may be used. In some Asian protocols, the strategy differs, often favoring upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation, reflecting biological and healthcare system differences.

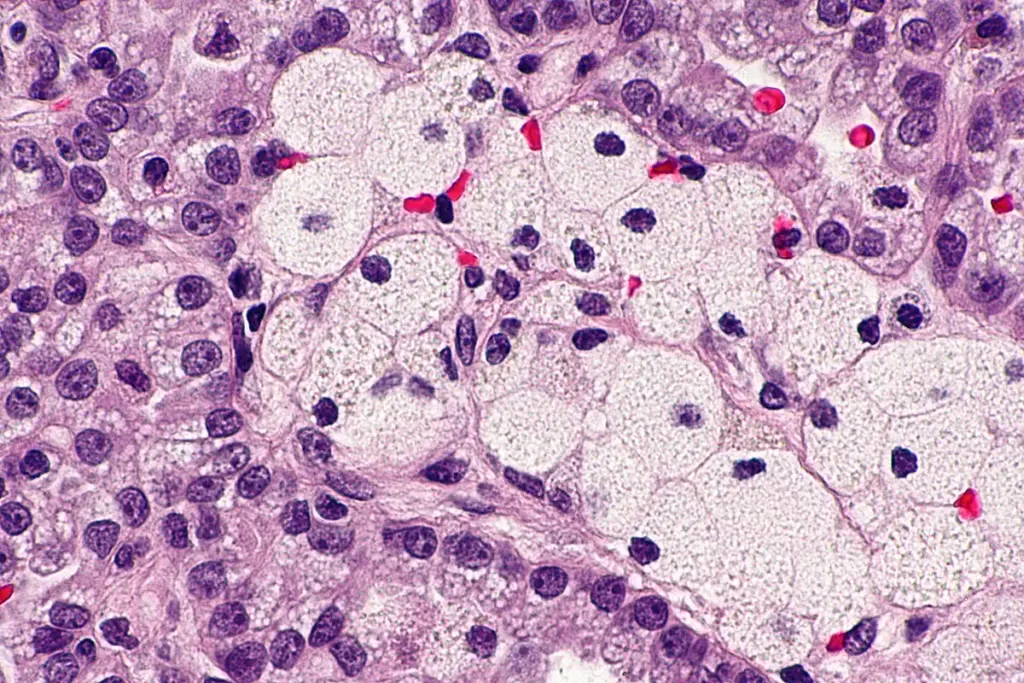

For advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, or for cases where surgery is not an option, systemic therapy is the primary treatment. This landscape has evolved from broad-spectrum cytotoxic drugs to precision medicine. As mentioned in the diagnosis, patients with HER2-positive tumors receive Trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy. This antibody binds to the HER2 receptor, blocking the growth signals and flagging the cell for immune destruction. Newer drugs like Trastuzumab Deruxtecan are showing promise even when standard treatments fail.

Immunotherapy has transformed the outlook for specific subsets. Checkpoint inhibitors like Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab are now approved for first-line treatment in combination with chemotherapy for tumors that express PD-L1 (CPS score > 5) or are MSI-High. These drugs unmask cancer cells, allowing the patient’s own T cells to recognize and attack the tumor. In MSI-High patients, responses can be durable and profound.

Another target is angiogenesis. Drugs like Ramucirumab inhibit VEGF, a protein that tumors use to grow new blood vessels. By cutting off the blood supply, the cancer is starved of oxygen and nutrients. These targeted agents are often used in the second-line setting after initial chemotherapy has stopped working.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Generally, no. Except for very early cancers removed endoscopically, surgery is required for a cure. Chemotherapy and radiation can shrink the tumor and control symptoms, but they rarely eliminate the primary solid mass. They are partners to surgery, not replacements for it in the curative setting.

Recovery is a significant process. Patients usually stay in the hospital for 7 to 10 days. It takes 6 to 8 weeks to recover from the surgical wounds and physical fatigue. However, the nutritional adaptation—learning to eat without a stomach—is a lifelong process that takes months to stabilize.

Historically, this was considered untreatable. However, modern approaches like HIPEC (Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy) are being explored. In selected cases, surgeons remove all visible disease and circulate heated chemotherapy directly in the abdomen during surgery. This is complex and performed only in specialized centers.

Giving chemo before surgery (neoadjuvant) attacks micrometastases that are too small to see on scans but are likely present. It also increases the likelihood that the surgeon can remove the entire tumor with clear margins (R0 resection). Studies show this approach improves overall survival compared to surgery first.

Yes, but its role varies. It is often used in combination with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) after surgery if the lymph node dissection was not adequate (less than D2). It is also used effectively for palliation to stop bleeding or relieve pain from obstruction in advanced cases.

Medical imaging tests, like CT scans, use contrast agents to make internal structures clearer. These substances are usually safe but can upset some people’s stomachs.

Can stomach cancer cause itchy skin? Many people are unaware that stomach cancer can present in unusual ways.. One of these is itchy skin. This

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)