Cardiology is the medical specialty focused on the heart and the cardiovascular system. It involves the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels. These conditions include coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), and valve disorders. The field covers a broad spectrum, from congenital heart defects present at birth to acquired conditions like heart attacks.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

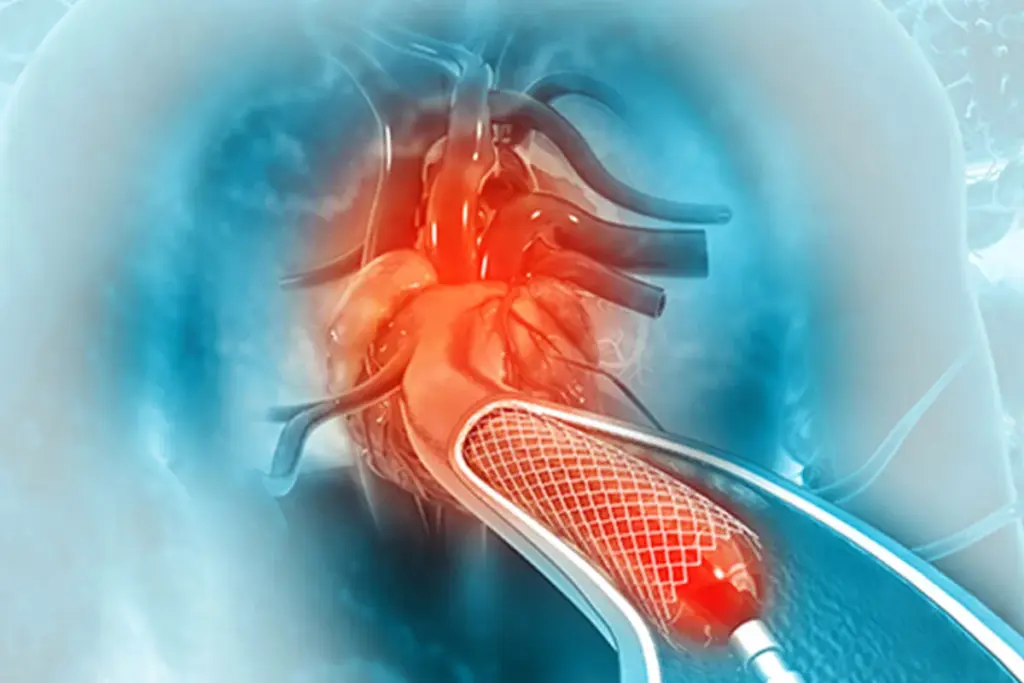

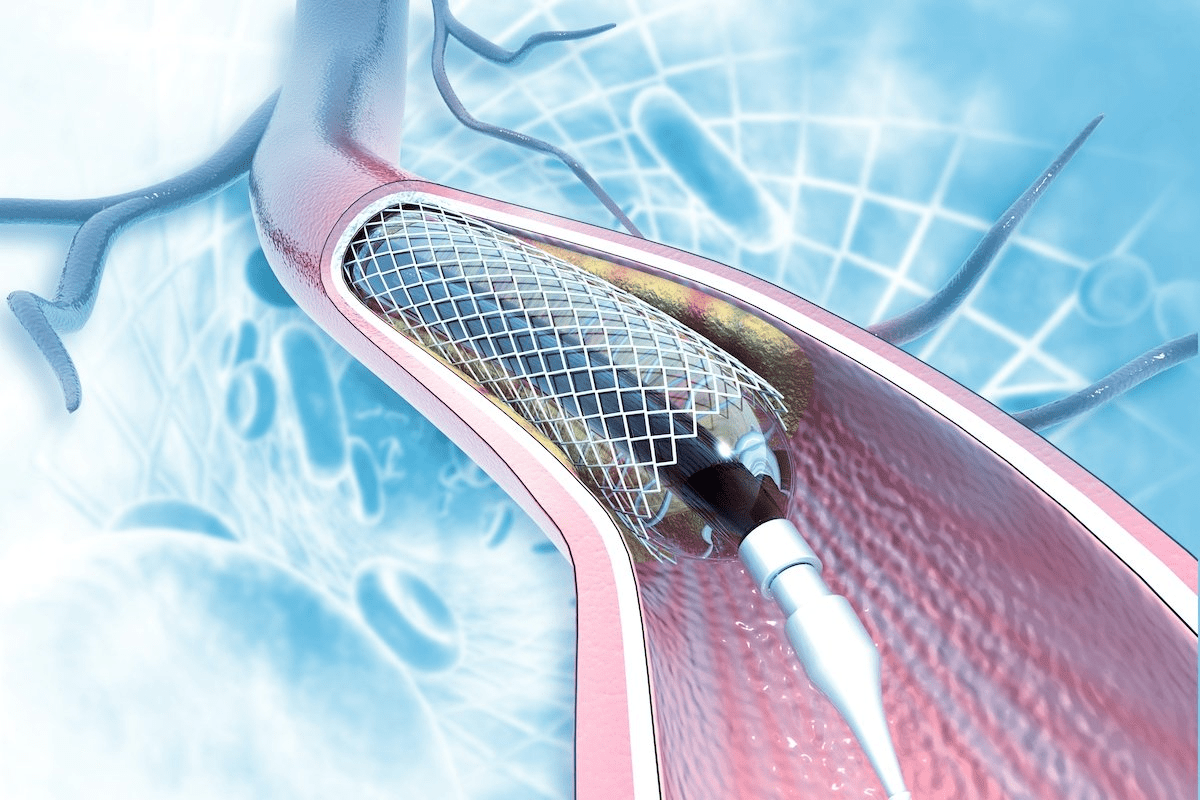

A coronary stent is a small, specialized medical device that plays a massive role in modern heart care. You can think of a stent as a tiny, expandable tube made of metal mesh, similar to a miniature scaffold or a spring found in a ballpoint pen. Its primary purpose is to act as a permanent support structure inside your coronary arteries. These arteries are the vital blood vessels that supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle itself. Over time, these vessels can become narrowed or blocked by a buildup of fatty deposits called plaque, a condition known as coronary artery disease. When an artery narrows, blood flow is restricted, which can lead to chest pain, shortness of breath, or a heart attack.

The application of a coronary stent is a procedure designed to reopen these narrowed pathways and keep them open for the long term. It is a minimally invasive treatment, meaning it does not require open-heart surgery or large incisions. Instead, doctors use long, thin tubes called catheters to place the stent exactly where it is needed. Once the stent is expanded against the artery wall, it locks in place and becomes a permanent part of your heart’s plumbing system. By restoring blood flow, stents help relieve symptoms, improve the quality of life, and, in emergency situations, save lives by stopping a heart attack in its tracks. Understanding this technology demystifies the process and helps patients feel more confident about their treatment plan.

The fundamental job of a coronary stent is to hold an artery open. Imagine a tunnel that has started to collapse or a garden hose that is being pinched. Water—or in this case, blood—cannot flow through efficiently. A stent acts like a tunnel liner. It is delivered to the blockage site in a collapsed, thin state. Once it is in the correct position, it is expanded. This expansion pushes the plaque buildup against the walls of the artery, widening the channel.

The stent is designed to be strong enough to resist the elastic recoil of the artery. Arteries are muscular tubes that naturally want to squeeze shut or return to their narrowed shape after being stretched. The metal mesh of the stent provides the structural integrity needed to prevent that from happening. It creates a smooth, wide scaffolding through which blood can flow freely, ensuring that the heart muscle receives the oxygen and nutrients it needs to pump effectively without strain.

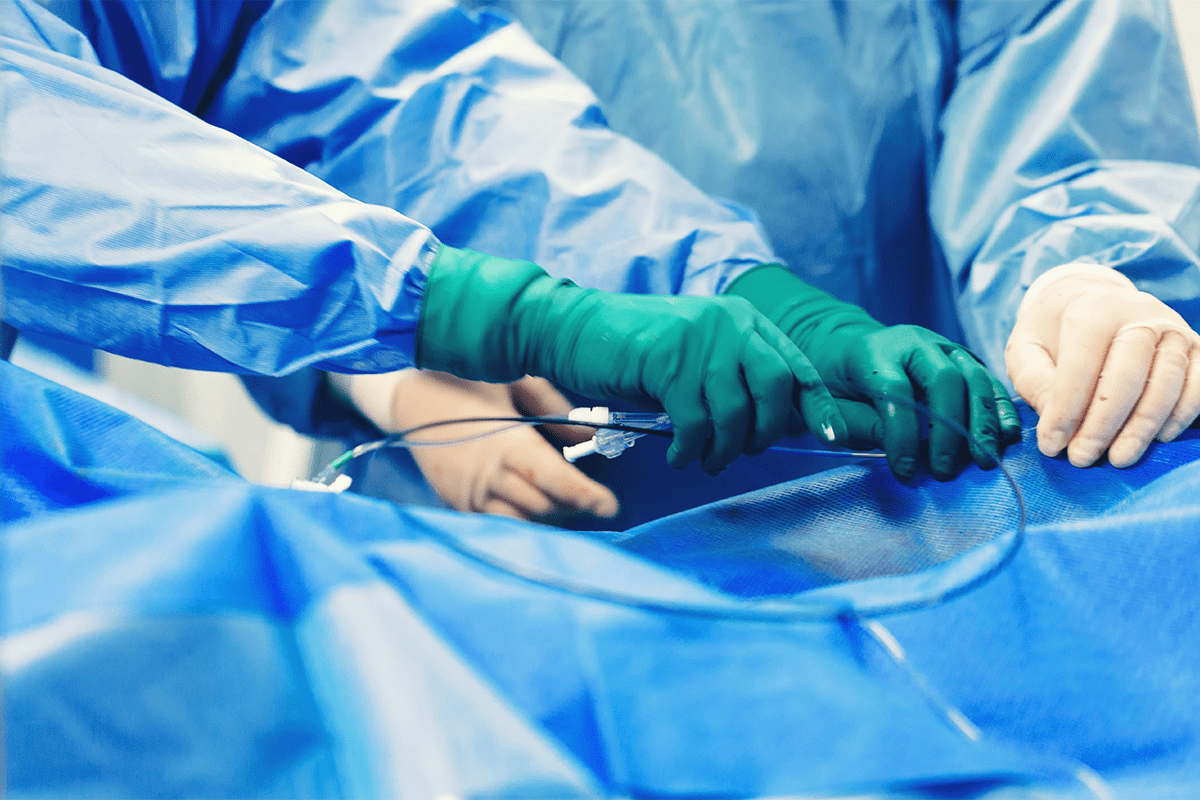

It is common to hear the terms “angioplasty” and “stenting” used together, and it is advantageous to understand the difference. Angioplasty is the technique used to open the artery, while the stent is the device left behind to keep it open. The procedure is formally known as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It begins with the doctor guiding a catheter tipped with a tiny, deflated balloon to the blockage.

Once the balloon is inside the narrowed section, it is inflated. The force of the balloon squashes the plaque and stretches the artery wall. In the past, this was often done without a stent, but doctors found that the arteries frequently collapsed or narrowed again (restenosis) shortly after. Today, the stent is almost always mounted on the outside of that balloon. When the balloon inflates, the stent expands with it. The balloon is then deflated and removed, but the stent stays expanded, locking the artery open.

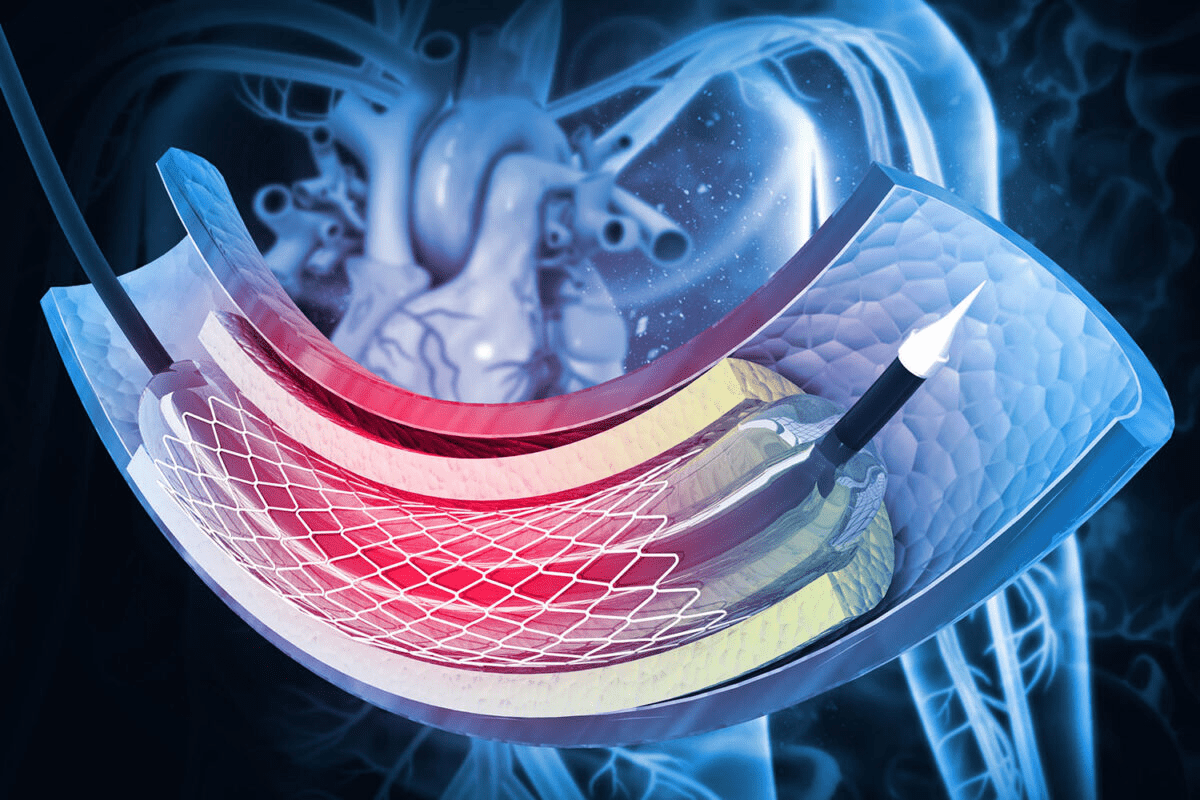

Not all stents are the same. Medical technology has evolved to produce different types of stents to address specific problems, particularly the issue of scar tissue growing over the device. The two main categories you will hear about are bare metal stents and drug-eluting stents. The choice of which stent to use depends on your specific anatomy, your risk of bleeding, and your ability to take blood-thinning medication for a prolonged period.

The development of these different types represents a history of doctors trying to solve the body’s natural reaction to a foreign object. When a metal object is placed in a blood vessel, the body tries to heal over it. Occasionally this healing is too aggressive, forming excess scar tissue that blocks the artery again. The different stent types are essentially different strategies for managing this healing process.

Bare Metal Stents (BMS) were the first generation of modern stents. As the name implies, they are mesh tubes made of stainless steel or cobalt-chromium alloys with no special coating. They provide excellent structural support and act as a strong scaffold. The advantage of a bare metal stent is that the artery heals over it relatively quickly. This means patients only need to be on strong blood-thinning medication for a shorter time, usually about a month. However, because they are bare metal, there is a higher risk that scar tissue will grow too much inside the stent, causing it to narrow again.

Drug-eluting stents (DES) are the standard of care for most patients today. These are metal stents coated with a special polymer that contains medication. Once the stent is implanted, it slowly releases this medication into the artery wall over several months. The medication is designed to stop scar tissue from growing too aggressively. This procedure drastically reduces the risk of the artery narrowing again (restenosis). The trade-off is that healing takes longer, so patients must take blood-thinning medication for a longer period, typically six months to a year, to prevent blood clots from forming on the exposed metal.

To appreciate where a stent goes, you need to visualize the heart’s fuel lines. The heart is a pump, but it also needs its blood supply to function. This supply of blood is provided by the coronary arteries, which wrap around the surface of the heart. There are two main systems: the left coronary artery and the right coronary artery. These split into smaller branches that dive deep into the heart muscles.

Depending on the vessel size and blockage location, stents can be placed in the large main arteries or smaller branches. The location matters because a blockage in a main artery affects a larger area of the heart muscle than a blockage in a tiny branch. Doctors use angiograms (X-ray movies) to map this plumbing system and decide exactly which pipe needs repair.

The primary reason a stent is necessary is ischemia, which is a medical term for a lack of oxygen. When plaque builds up, it acts like sludge in a pipe. Only a trickle of blood can pass through a pipe that is 90% blocked. At rest, the flow might be enough. But when you exert yourself—walking up stairs or feeling stressed—the heart beats faster and needs more blood. The blocked artery cannot deliver it.

This supply-and-demand mismatch causes symptoms like chest pain (angina). If the plaque ruptures, a clot forms and blocks the pipe 100 percent. The outcome is a heart attack. A stent is necessary to mechanically push that blockage aside and restore full flow. It turns a narrow, inefficient stream back into a rushing river, ensuring the heart muscle receives the fuel it needs to do its job without straining or dying.

The concept of opening arteries without major surgery began in the late 1970s with simple balloon angioplasty. While revolutionary, it had limitations; arteries would often recoil or tear. The first stents were introduced in the 1980s and 1990s to solve these mechanical issues. These early versions were bulky and difficult to maneuver.

Over the decades, engineering has refined these devices significantly. Modern stents are incredibly flexible, allowing them to travel through twisting arteries. They are thinner, causing less injury to the vessel wall. The drugs used on coated stents have become safer and more effective. Today, the procedure is so refined that it is routine, with high success rates and very low complication rates, transforming what used to be a major medical crisis into a manageable condition.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

No, you will not feel the stent. The inside of your arteries does not have nerve endings that sense touch or pressure. Once the stent is implanted, you will not be aware of its presence, and it will not cause any sensation of weight or discomfort.

No, a coronary stent will not set off metal detectors at airports or security checkpoints. The amount of metal in a stent is incredibly small, and it is made of non-ferrous (non-magnetic) materials like stainless steel or cobalt-chromium alloys that security scanners generally ignore.

Yes, most modern coronary stents are MRI-safe. However, it is important to tell the MRI technician that you have a stent and, if possible, show them your stent implant card. They may need to adjust the scanner settings, but it typically does not prevent you from having the scan.

Coronary stents are permanent implants. They are designed to remain in your artery for the rest of your life. They do not wear out, and they do not need to be removed or replaced. The body’s tissue eventually grows over the stent, incorporating it into the artery wall.

Yes, most patients are awake during the procedure. You are given a sedative to help you relax and feel sleepy, but you are usually conscious enough to follow instructions, such as taking a deep breath. You won’t feel pain because local anesthesia numbs the catheter entry site.

Heart stents are used to open clogged arteries. They help improve blood flow to the heart. But, sometimes, these stents can become blocked again. This

Knowing when a stent or bypass surgery is needed is key for both patients and doctors. At Liv Hospital, we focus on you, with top-notch

Every year, thousands of patients worldwide get help for blocked heart arteries. Choosing between minimally invasive treatments is a big decision. At Liv Hospital, we

Learning about a coronary stent procedure is important for heart health. At Liv Hospital, we think education is key. A coronary stent procedure video shows

At Liv Hospital, we know patients often ask about heart stent limits. The number of heart stents a person can have varies. It depends on

Coronary artery disease affects millions worldwide. For many, a stent procedure is a lifesaving intervention. But what does this mean for patients facing the prospect

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)