Plastic surgery restores form and function through reconstructive procedures, cosmetic enhancements, and body contouring.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Facial asymmetry correction is a comprehensive field of plastic and reconstructive surgery dedicated to restoring balance and proportion to the human face. It operates on the understanding that while absolute symmetry is biologically impossible and often aesthetically unnatural, significant deviations can disrupt facial harmony. The goal is not to create a mirror image but to establish an equilibrium where the left and right sides complement each other seamlessly.

Surgeons view asymmetry as a multidimensional puzzle involving the skeletal foundation, the soft-tissue envelope, and the dynamic neuromuscular system. Correcting these imbalances requires a deep understanding of craniofacial growth patterns and the aging process. The procedure aims to center the facial midline and harmonize the features relative to that axis.

This discipline integrates principles from maxillofacial surgery, aesthetic plastic surgery, and dermatology. It addresses congenital differences that have existed since birth as well as acquired asymmetries resulting from trauma, lifestyle, or uneven aging. The definition of success is a face that appears balanced to the casual observer and functions correctly.

Modern approaches emphasize the preservation of the patient’s unique identity. The correction aims to remove the distraction of the asymmetry, allowing the patient’s natural beauty to be appreciated without visual interruption. It is a restorative process that aligns the patient’s external appearance with their internal sense of self.

A fundamental distinction in defining facial asymmetry is determining whether the cause is skeletal or soft-tissue. Skeletal asymmetry involves the bones of the face, including the mandible, maxilla, cheekbones, and orbit. These structural discrepancies often require surgical manipulation of the bone to achieve a lasting correction.

Soft tissue asymmetry involves the fat pads, muscles, and skin. This can manifest as uneven volume, different eyebrow heights, or varying degrees of skin laxity. Distinguishing between these two etiologies is the first step in diagnosis, although most patients present with a combination of both.

Skeletal asymmetry often dictates the face’s “frame.” If the frame is crooked, the soft tissue “canvas” will drape unevenly. Therefore, addressing the bone is often the primary step in significant corrections. This provides a stable foundation for subsequent soft-tissue refinements.

Soft tissue asymmetry can be dynamic or static. Dynamic asymmetry appears only when the face is moving, such as smiling or talking, and is usually related to nerve or muscle function. Static asymmetry is present at rest. Understanding this difference defines the treatment pathway, distinguishing between surgical restructuring and neuromuscular modulation.

Many cases of facial asymmetry are congenital, meaning they are present at birth or develop during growth spurts. Conditions such as hemifacial microsomia or plagiocephaly affect the development of the jaw, ear, and cheek on one side. These developmental pathways create a template that persists into adulthood.

Even without a specific syndrome, genetic traits often show uneven expression. One side of the face may naturally grow faster or larger than the other. This developmental variance is normal to a degree but becomes a clinical concern when it affects function or causes psychosocial distress.

Understanding the developmental origin helps surgeons predict how the face will continue to age. Tissues that failed to develop fully in youth often age faster or differently than the unaffected side. The surgical plan must account for these longitudinal changes.

Developmental asymmetry often involves the teeth and the bite (occlusal asymmetry). The jaw may deviate to one side, causing a crossbite. In these cases, the procedure definition expands to include functional orthognathic surgery to correct the bite and the aesthetic appearance.

Acquired asymmetry refers to imbalances that develop after birth due to external factors. Trauma is a leading cause, where fractures of the nose, cheek, or jaw heal in a malaligned position. This alters the underlying skeleton and can trap soft tissues, leading to scarring and volume loss.

The definition of correction in trauma cases involves refracturing or repositioning bones to their pre-injury state. It is a reconstructive effort to reverse the damage and restore the original facial architecture. This often requires complex mapping of the distorted anatomy.

Acquired asymmetry can also result from medical conditions like Bell’s Palsy or tumors. Nerve damage leads to muscle atrophy on the affected side and hypertonicity on the healthy side, as the healthy side overcompensates. The treatment here is defined by reanimation and static suspension.

Lifestyle factors also play a role. Chewing predominantly on one side can lead to hypertrophy of the masseter muscle, making one jaw angle appear wider. Sleeping on one side for decades can contribute to deeper sleep lines and tissue flattening. These functional habits define the acquired structural changes.

Volume loss is a key component of facial aging and asymmetry. As we age, facial fat pads deflate and shift. This process rarely happens symmetrically. One side of the face may lose volume faster, leading to a deeper nasolabial fold or a lower cheek position on that side.

Facial asymmetry correction defines volume restoration as a critical pillar of treatment. By refilling these deflated compartments with fat grafting or implants, surgeons can restore balance without pulling the skin tight. This volumetric approach addresses the deflationary component of the imbalance.

This concept extends to the lips and perioral region. Uneven volume loss in the lips can create a crooked smile. Correcting this involves precise micro-augmentation to match the volume of the opposing side. The definition of symmetry here is measured in millimeters of projection and fullness.

Volumetric correction also camouflages underlying skeletal discrepancies. If a patient is not a candidate for bone surgery, adding volume to the deficient side can create the illusion of skeletal symmetry. This “camouflage” technique is a valid, less invasive approach to correction.

The face is a dynamic organ of communication. Asymmetry is often most visible during movement. When a person smiles, talks, or blinks, the muscles may contract unevenly. This dynamic asymmetry is defined by the function of the facial nerve and the strength of the mimetic muscles.

Correction involves modulating these muscle forces. This can be achieved by selectively weakening hyperactive muscles (using neurotoxins or surgery) or by strengthening/reanimating weak muscles. The goal is to synchronize the movement of both sides of the face.

The concept of “synkinesis” is relevant here, in which voluntary movement of one muscle triggers involuntary movement of another. This often occurs after nerve injury recovery. Defining the specific pattern of aberrant muscle firing allows for targeted treatment to separate and control these movements.

Understanding the vector of muscle pull is essential. Muscles pull against the skin and bone to create expression. If the anchor points are asymmetrical, the expression will be too. Releasing or repositioning these anchor points is part of the surgical definition of dynamic correction.

Facial analysis relies on a grid of vertical and horizontal reference lines. The central vertical meridian divides the face into two halves. In asymmetry correction, the surgeon defines how far each feature (nose, chin, dental midline) deviates from this central axis.

Horizontal lines connect the pupils, the cheekbones, and the corners of the mouth. Ideally, these lines should be parallel to the floor. Asymmetry often presents as a “cant,” where these horizontal planes are tilted. Correcting the cant is a primary definition of skeletal realignment procedures.

The vertical height of the face is also analyzed. One side of the face (hemiface) may be vertically shorter than the other, causing the eye, ear, and mouth corner to sit higher. This three-dimensional distortion requires a complex understanding of spatial geometry to correct.

Surgeons use cephalometric analysis to define these planes scientifically. This moves the diagnosis from a subjective “it looks crooked” to an objective measurement of degrees and millimeters. This quantitative definition guides the precise surgical movements required.

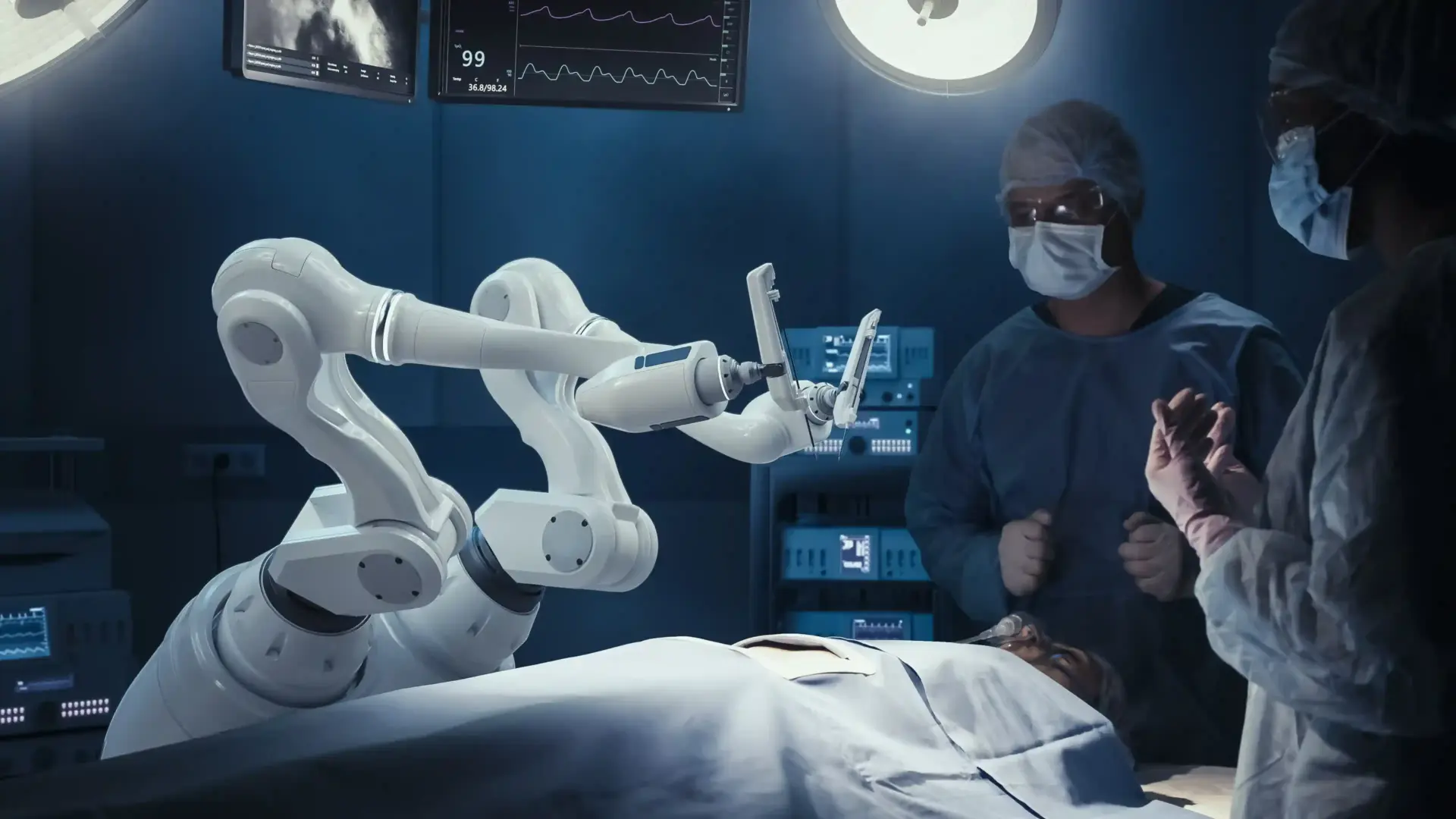

The modern definition of facial asymmetry correction is inextricably linked to technology. High-resolution CT scans and 3D photography allow surgeons to visualize the skull and soft tissue in exquisite detail. This eliminates guesswork and provides a roadmap for the internal anatomy.

Computer-aided design (CAD) allows for virtual surgical planning (VSP). The surgeon can perform the surgery on a computer screen before ever touching the patient. This defines the exact cutting planes and movement vectors needed to achieve symmetry.

This technology extends to the fabrication of custom implants and surgical guides. If one side of the jaw is deficient, a custom implant can be 3D printed to match the other side perfectly. This capability defines the current era of personalized reconstructive surgery.

Intraoperative navigation serves as a GPS for the surgeon. It allows real-time tracking of anatomical structures during the procedure, ensuring that the execution matches the virtual plan. This technological integration defines the safety and accuracy of modern correction.

The face is the primary marker of identity. Asymmetry can lead to significant self-consciousness, social anxiety, and avoidance of photography or social interaction. The definition of correction extends beyond the physical to the psychosocial restoration of the patient.

Patients often develop compensatory behaviors, such as tilting their head or covering one side of their face with hair. Successful correction allows the patient to abandon these behaviors. It is a liberation from the constant awareness of the imbalance.

The consultation process involves assessing the patient’s motivation. The goal is to achieve improvement and harmony, not perfection. Defining realistic expectations is a crucial part of the therapeutic alliance. The surgery is successful when the patient feels their external appearance aligns with their inner self.

Surgeons acknowledge the “mirror phenomenon,” in which patients are more critical of their asymmetry in a mirror than others are in person. Correcting the asymmetry helps reconcile these differing perceptions, leading to a unified and positive self-image.

The field is increasingly incorporating regenerative medicine. This involves using the body’s own signaling cells to improve tissue quality. Fat grafting is not just for volume; the stem cells within the fat can rejuvenate the overlying skin and soften scar tissue from previous trauma.

This biological definition of correction focuses on the quality of the tissue rather than its position. Improving skin elasticity and thickness helps the soft tissue drape more symmetrically over the facial skeleton. It addresses the “fabric” of the face alongside the “frame.”

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and nanofat are used to treat fine irregularities and improve circulation. This is particularly relevant in cases of hemifacial atrophy or radiation damage. The definition of correction now includes optimizing the biological environment of the facial tissues.

By combining structural surgery with regenerative therapies, surgeons can achieve results that look natural and age well. This holistic approach ensures that the corrected face maintains its symmetry and vitality over time.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Almost every human face has some degree of asymmetry. “Normal” asymmetry is subtle and usually not noticed in daily interaction. It becomes a clinical concern when the deviation is significant enough to distract from the overall facial harmony or cause functional issues with chewing, speaking, or vision.

It spans both categories. If the asymmetry is due to a congenital disability, trauma, or causes functional problems (like jaw pain or vision obstruction), it is often classified as reconstructive. If the concern is purely regarding appearance without functional impairment, it is considered cosmetic.

Facial exercises cannot change the underlying bone structure, which is the primary cause of most significant asymmetry. While they might slightly tone muscles, they cannot correct deviations of the jaw, chin, or orbits, and in some cases, may exacerbate muscle imbalance.

Correction can be performed once facial growth is complete, typically in the late teens (17-18 for females, 18-21 for males). However, severe congenital cases or trauma may require intervention during childhood, often in multiple stages, to guide proper growth.

Modern techniques prioritize “stealth” incisions. Many procedures are performed inside the mouth (intraoral) or through hidden incisions in the eyelid crease, nose, or hairline. The goal is to make any necessary external scars as inconspicuous as possible.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)