Plastic surgery restores form and function through reconstructive procedures, cosmetic enhancements, and body contouring.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Diastasis recti is a condition defined by the separation of the rectus abdominis muscles, which run vertically along the front of the abdomen. This separation occurs at the linea alba, the midline connective tissue that connects the muscle bellies. When this tissue stretches and thins, the muscles drift apart, creating a gap that compromises the abdominal wall’s structural integrity.

This condition is not merely aesthetic; it represents a functional failure of the core containment system. Patients often present with a visible bulge or ridge running down the center of their stomach, particularly when engaging their core muscles. This lack of support can lead to secondary issues such as lower back pain and pelvic floor dysfunction.

Skin laxity, or dermatochalasis, refers to the loss of skin elasticity and its subsequent inability to retract to the body’s contours. In the context of reconstructive surgery, this often manifests as hanging folds of tissue, particularly after massive weight loss or aging. The skin loses its structural proteins, collagen and elastin, becoming thin and non-resilient.

This condition creates physical and hygiene challenges. Deep folds of skin can trap moisture and bacteria, leading to chronic rashes and infections. The excess tissue can also be heavy and uncomfortable, mechanically restricting movement and making it difficult to find properly fitting clothing.

Persistent adipose tissue refers to localized deposits of subcutaneous fat that are resistant to diet and exercise. In reconstructive patients, these deposits can be asymmetrical or disproportionate, often resulting from trauma, previous surgeries, or congenital conditions. This is distinct from general obesity; it is a localized contour deformity.

These fat deposits can obscure the underlying muscular anatomy and create irregular body contours. Reconstructive efforts often involve addressing these deposits to smooth the transition between reconstructed areas and the surrounding normal tissue, ensuring a harmonious result.

Pregnancy induces profound physiological changes that can leave lasting impacts on the body’s structure. The abdominal wall undergoes immense stretching, which can permanently alter the fascial integrity and skin quality. Beyond diastasis recti, women may experience umbilical hernias and significant loss of skin elasticity.

Reconstructive procedures address these sequelae by restoring the abdominal wall’s tensile strength. The goal is to restore the musculature to its pre-pregnancy anatomical position and remove the damaged, non-contractile skin that can no longer effectively support the abdominal contents.

Following massive weight loss, whether through bariatric surgery or lifestyle changes, patients are often left with significant redundant skin. The skin envelope, having been stretched for prolonged periods, fails to shrink back to the smaller body volume. This results in circumferential excess tissue on the abdomen, arms, thighs, and back.

This condition is functionally debilitating. The excess skin acts as a dead weight, causing fatigue and impeding the active lifestyle the patient has worked to achieve. Reconstructive body contouring removes excess skin to complete the patient’s weight-loss journey and restore functional mobility.

Aging causes a systemic decline in tissue quality, affecting all reconstructive outcomes. The natural loss of collagen, bone resorption, and redistribution of fat compartments contribute to sagging and volume loss. In reconstructive surgery, these factors must be accounted for to ensure the repair ages naturally with the patient.

The thinning of the dermis makes the skin more fragile and less able to hide underlying irregularities. Surgeons must often employ techniques to add volume or thickness, such as fat grafting, to counteract these age-related changes and provide durable coverage.

Genetics plays a crucial role in determining tissue quality, healing potential, and predisposition to certain deformities. Some patients have genetically weaker connective tissue, making them more prone to hernias, varying degrees of skin laxity, and poor scar formation. Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are extreme examples of this.

Understanding a patient’s genetic background helps the surgeon predict how their tissues will handle surgical manipulation and healing. It influences the choice of technique, such as using mesh reinforcement in patients with inherently weak fascia to prevent recurrence.

A weakened abdominal wall directly impacts posture and core stability. The abdominal muscles act as the anterior support for the spine. When this support is compromised, as in diastasis recti or after abdominal trauma, the back muscles must overcompensate, leading to chronic strain and lordosis (swayback).

Reconstructive repair of the abdominal wall restores the cylinder of stability required for proper spinal alignment. Patients often report significant improvements in back pain and posture once the anterior muscular integrity is re-established.

Hernias occur when internal organs or tissues push through a weak spot in the surrounding muscle or connective tissue (fascia). In reconstructive patients, these are often incisional hernias resulting from previous surgeries or ventral hernias due to congenital weakness. They present as bulges that may enlarge with coughing or straining.

Repairing these defects is a core component of abdominal reconstruction. It involves reducing the herniated contents back into the abdominal cavity and reinforcing the defect, often with prosthetic mesh, to prevent recurrence and restore the abdominal wall’s continuity.

Scar contracture is a tightening of the skin that occurs after second-degree or third-degree burns or deep trauma. As the wound heals, the scar tissue shrinks, pulling the edges of the skin together. When this occurs over a joint, it can severely restrict movement and freeze the limb in a flexed position.

Reconstructive surgery releases these contractures to restore the range of motion. This often involves excising the scar tissue and replacing it with a skin graft or flap that provides ample healthy tissue, allowing the joint to extend fully again.

Congenital anomalies are structural defects present at birth that can affect any part of the body. Common examples requiring reconstruction include cleft lip and palate, microtia (underdeveloped ear), and syndactyly (fused fingers). These conditions can affect feeding, speech, hearing, and hand function.

Reconstruction aims to normalize the anatomy early in life to support proper development. These procedures are often staged over several years to accommodate the child’s growth, using local tissues to recreate complex structures such as the lip, palate, or ear.

Facial palsy results from damage to the facial nerve, causing paralysis of the muscles of facial expression. This leads to functional issues such as inability to close the eye, difficulty speaking and eating, and significant facial asymmetry. It can be congenital or acquired through trauma, Bell’s palsy, or tumor resection.

Reconstructive options range from static procedures that suspend the face to improve symmetry at rest to dynamic muscle transfers. Dynamic procedures involve moving a muscle, such as the temporalis or gracilis, to the face and connecting it to a nerve source to restore the ability to smile.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

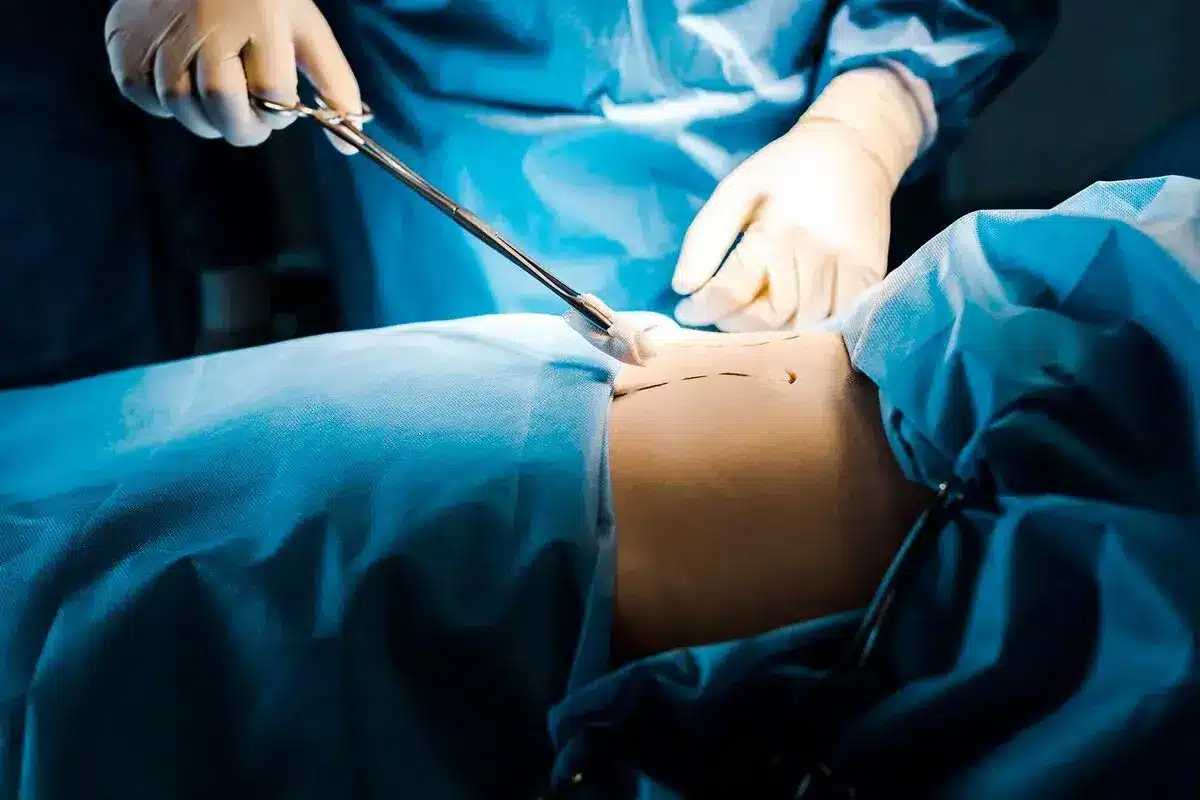

A tummy tuck is often cosmetic, focusing on removing skin and fat. Reconstructive abdominal surgery, usually called a panniculectomy or abdominal wall reconstruction, focuses on repairing hernias, correcting muscle separation that causes pain, or removing excess skin that can lead to chronic infections.

If your back pain is caused by a severe separation of your abdominal muscles (diastasis recti) or a large hernia, repairing the abdominal wall can often alleviate the pain by restoring proper core support and spinal alignment.

Insurance coverage varies. Typically, insurance will cover the removal of the hanging apron of skin (panniculectomy) if it causes documented medical issues, such as chronic rashes or ulcers that don’t respond to treatment. It rarely covers circumferential body lifts.

Yes, if the nerve injury is identified early. Microsurgery can reconnect severed nerves. If the gap is too large, a nerve graft from another part of the body can be used to bridge it and guide regenerating nerve fibers.

Yes, immediate reconstruction is very common and often preferred. It allows the surgeon to preserve the breast skin envelope, leading to a more natural result and sparing the patient the experience of waking up with no breast mound.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)