Stem cells can develop into many cell types and act as the body’s repair system. They replace or restore damaged tissues, offering new possibilities for treating diseases.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Multiple myeloma is not a sudden event but rather the culmination of a progressive spectrum of plasma cell disorders. Understanding this progression is vital for determining the appropriate indication for intervention. The disease typically evolves through asymptomatic precursor stages before becoming “active” myeloma requiring treatment.

The acronym CRAB often serves as a reminder of the hallmark features of active myeloma and of indications for initiating therapy. These symptoms reflect the systemic impact of the plasma cell proliferation and the accumulation of M-proteins.

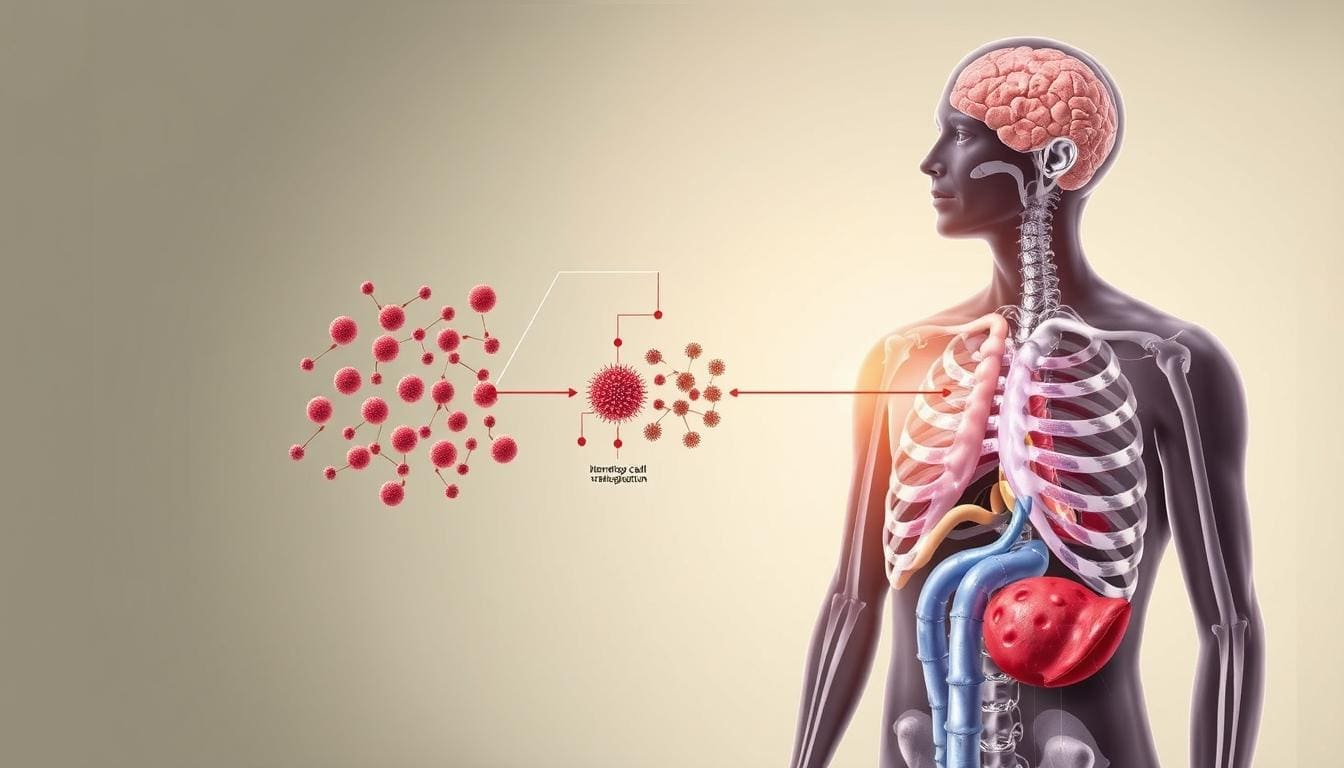

In a subset of patients, the light chains produced by the plasma cells misfold and form insoluble protein fibers called amyloid. These fibers deposit in organs such as the heart, kidneys, nerves, and digestive tract, causing a condition called AL Amyloidosis. While distinct from classic myeloma, it is a related plasma cell dyscrasia that is often treated with similar strategies, including stem cell transplantation, to stop the production of the amyloid-forming protein.

Additionally, patients often present with recurrent infections. Because the malignant plasma cells produce useless M-proteins and suppress the production of normal, functional antibodies, the patient effectively has a compromised immune system (hypogammaglobulinemia), making them susceptible to pneumonia and other bacterial infections.

While the exact cause of the genetic mutations initiating myeloma remains elusive, several risk factors have been identified that may contribute to the condition:

Not all patients with myeloma are immediate candidates for regenerative therapies like stem cell transplantation. The indication is based on a careful assessment of “transplant eligibility.”

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Smoldering myeloma is a state in which laboratory values indicate myeloma (elevated M-protein or plasma cells). Still, the patient has no symptoms and no organ damage (no CRAB features). It is a “waiting room” between benign MGUS and active cancer. It typically requires close observation rather than immediate chemotherapy.

Yes, myeloma is often detected incidentally during routine blood work for other conditions. A finding of elevated total protein or anemia might trigger further testing that reveals the M-protein. Detecting the disease at the MGUS or Smoldering stage allows for monitoring, ensuring treatment begins exactly when necessary to prevent bone or kidney damage.

Myeloma cells secrete chemicals that activate osteoclasts (bone-destroying cells) and inhibit osteoblasts (bone-building cells). This leads to weak, brittle bones and the formation of lytic lesions. The pain is caused by micro-fractures, significant fractures, or the stretching of the bone lining (periosteum) by the expanding tumor mass.

In some cases, the level of M-protein in the blood becomes so high that it thickens the blood, making it sludge-like. This is called hyperviscosity. It can slow down blood flow to the brain and eyes, causing dizziness, confusion, vision changes, and headaches, and requires urgent treatment to filter the blood (plasmapheresis).

No. Most people with MGUS never develop multiple myeloma. The risk of progression is estimated at approximately 1% per year. Many individuals live their entire lives with MGUS without it ever evolving into a malignancy, though lifelong monitoring is recommended.

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)