Cancer involves abnormal cells growing uncontrollably, invading nearby tissues, and spreading to other parts of the body through metastasis.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Sarcoma is a diverse and complex group of cancers that develop from mesenchymal tissue, not from the epithelial lining of organs like carcinomas. Mesenchymal tissue is the early connective tissue that forms the body’s framework. In modern medicine, sarcoma means a cancer that starts in mesodermal tissue, which later becomes bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, blood vessels, and fibrous tissue. Unlike epithelial cancers, which often behave in similar ways, sarcomas are very varied, with over seventy different types that can act and respond to treatment in many different ways. Sarcoma mainly affects the body’s support structures, disrupting the tissues that hold everything together.

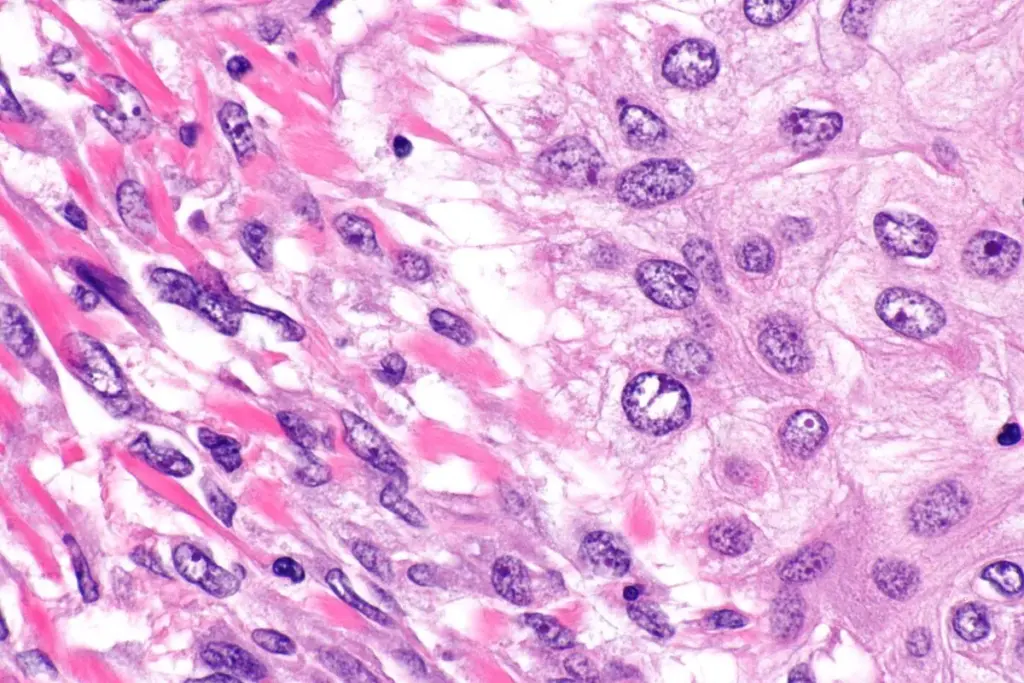

Today, doctors understand sarcoma by looking at how it develops and the genetic changes that cause it. While carcinomas usually result from years of environmental damage to DNA, many sarcomas, especially in children and young adults, are caused by sudden chromosomal changes called translocations. These changes join two different genes, creating a new protein that disrupts normal cell function. Because of this, sarcomas are now classified not just by how the cells look under a microscope, but by the specific genetic changes that drive their growth. This new approach helps doctors choose treatments based on the tumor’s genetics, not just its location.

In regenerative medicine, sarcoma is seen as a breakdown in the body’s ability to repair itself. Mesenchymal stem cells, which can become bone, cartilage, or fat cells, normally help heal injuries. In sarcoma, this process stops, and the cells start growing out of control. These cancer cells keep some of the qualities of stem cells, like the ability to move and multiply, but they can’t fully mature into healthy tissue. Because of this, doctors now see sarcoma as a problem with cell development, and treatments are being developed to help these cells mature or to target the features that keep them in a stem-like state.

The type of cell where a sarcoma starts determines how it is classified and how aggressive it might be. Sarcomas are usually divided into soft tissue sarcomas and bone sarcomas, but many types share similar genetic features. Most sarcomas are soft tissue sarcomas, which begin in muscles, fat, nerves, or deep layers of skin. For example, liposarcoma comes from early fat cells, leiomyosarcoma starts in smooth muscle cells (like those in blood vessels or the uterus), and rhabdomyosarcoma, which mostly affects children, resembles developing skeletal muscle.

Bone sarcomas, such as Osteosarcoma and Chondrosarcoma, arise from specialized cells that mineralize the skeleton. In Osteosarcoma, the malignant osteoblast produces an aberrant, unmineralized bone matrix called osteoid. This production of matrix by the tumor cells themselves is a defining feature of sarcomas. Unlike carcinomas, which induce surrounding normal cells to form a supporting stroma, sarcoma cells are autonomous matrix builders. They synthesize their own extracellular environment, creating a dense, often pressurized tumor microenvironment that acts as a physical barrier to drug delivery and immune cell infiltration. This autologous matrix production is a key target for novel therapies that aim to disrupt tumor structural integrity.

Molecular Subtypes and Fusion Oncogenes

Sarcoma tumors are unusual because their cancer cells build most of the surrounding support structure, called the extracellular matrix (ECM). Normally, the ECM helps support tissues and controls how cells behave. In sarcoma, the cancer cells make an abnormal, much stiffer matrix by producing unusual proteins and enzymes. This stiffness triggers signals inside the cells that help them survive, grow, and resist treatment.

The environment around a sarcoma tumor is often called ‘immune cold’ because the thick, abnormal matrix blocks immune cells from reaching the cancer. Sarcoma cells also release substances that turn helpful immune cells into ones that protect the tumor instead. Learning how this barrier works is important for creating new immunotherapy treatments. Today, understanding and breaking down this protective layer is a key part of treating sarcoma.

Global biotechnology is revolutionizing the classification and management of sarcoma by integrating Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and advanced molecular pathology. The traditional reliance on histopathology—looking at cell shape and staining patterns—is being augmented, and in some cases replaced, by genomic profiling. This “molecular reclassification” has revealed that many tumors previously categorized as “Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma” actually belong to distinct molecular subtypes with targeted therapy options.

Modern care for sarcoma now uses liquid biopsy, a blood test that looks for tumor DNA. Since sarcomas often release DNA into the blood, doctors can find specific gene changes, like EWS-FLI1, without surgery. This helps track the cancer, spot recurrences early, and see if the tumor is becoming resistant to treatment. Researchers also use patient tumor samples to grow models in the lab, which helps them test drugs and move toward more personalized treatments.

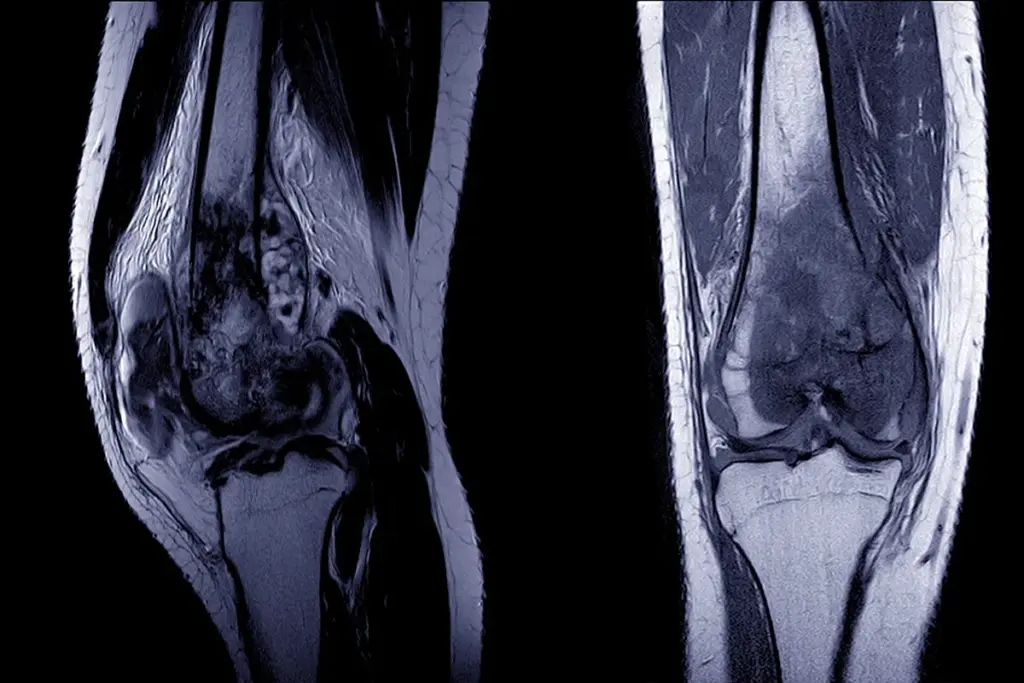

In regenerative medicine, treating sarcoma often means focusing on rebuilding function. Since these tumors usually grow in the limbs or trunk, surgery may require removing important bone, muscle, or nerves. Success in surgery now means not just removing the tumor, but also saving the limb and restoring movement. Surgeons use large bone grafts, 3D-printed metal implants, and engineered tissue to replace what was removed.

Research into tissue engineering aims to develop bioscaffolds seeded with the patient’s own stem cells to regenerate bone and muscle defects resulting from sarcoma resection. This regenerative approach seeks to restore the biomechanical integrity of the musculoskeletal system, allowing patients to retain mobility and quality of life. The intersection of oncology and regenerative engineering is most poignant in pediatric sarcoma, where reconstruction must not only restore function but also accommodate the child’s future growth.

Key Physiological Functions Compromised

Sarcoma cells use energy differently than normal connective tissue cells. They often change their metabolism to grow quickly, even when nutrients are low inside the tumor. This means they rely more on certain processes, like aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg Effect) and using glutamine. Aggressive sarcomas also have high activity in their energy centers and produce more harmful byproducts, which they manage by boosting their own protective systems. Learning how sarcoma cells get their energy helps researchers find new drugs that can block these pathways and slow tumor growth.

Send us all your questions or requests, and our expert team will assist you.

Sarcomas and carcinomas arise from different embryonic tissues. Carcinomas arise from epithelial cells that line the surfaces and organs of the body (such as the skin, lungs, or breast). Sarcomas arise from mesenchymal cells, which form the connective tissues (bone, muscle, fat, cartilage, and blood vessels). Because they start in different tissues, they behave differently, spread to other locations, and require various treatments.

Sarcomas are considered “orphan diseases” because they are relatively rare compared to other cancers, accounting for only about 1% of all adult malignancies. Because they are rare and extremely diverse (with over 70 subtypes), they have historically received less research funding and attention than common cancers. This underscores the critical role of specialized care at high-volume sarcoma centers in accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

A fusion gene occurs when parts of two different chromosomes break off and switch places (translocation), joining two genes that are usually separate. This creates a new, abnormal gene that produces a fusion protein. This protein acts like a permanently “on” switch for cell growth. Fusion genes are the primary cause of many sarcomas, such as Ewing Sarcoma and Synovial Sarcoma, and serve as specific targets for diagnosis and treatment.

No, the vast majority of lumps found in soft tissue are benign (non-cancerous). Common benign lumps include lipomas (fatty tumors), cysts, and fibromas. However, a soft tissue lump that is larger than a golf ball (5cm), growing in size, painful, or located deep within the muscle (deep to the fascia) should be evaluated by a specialist to rule out sarcoma, as these are “red flag” symptoms.

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM) is the structural web of proteins (like collagen) that surrounds cells. In sarcoma, the cancer cells themselves produce an abnormal, stiff ECM. This stiff matrix protects the tumor from the immune system, prevents chemotherapy drugs from penetrating deep into the tumor, and provides a pathway for cancer cells to migrate and spread to other parts of the body.

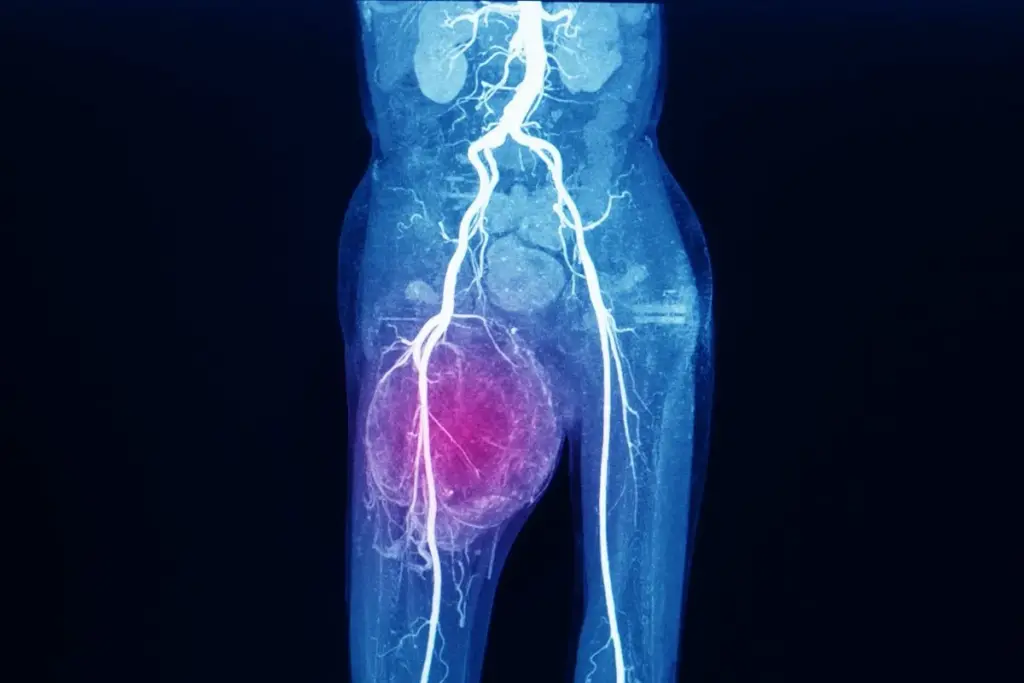

Finding bone cancer early is key to treating it well. We use advanced tools like PET scans to spot it. A PET scan shows how

Finding bone cancer early is key to better treatment and results. At Liv Hospital, we use top-notch diagnostic tools. This ensures we catch it right.

Finding bone cancer early is key to good treatment. Tests like PET scans, MRI, CT scans, and blood tests are important. They help us see

Bone scintigraphy is a detailed nuclear medicine imaging method. It helps find and diagnose different bone diseases. This includes fractures, infections, and cancer. A bone

Leave your phone number and our medical team will call you back to discuss your healthcare needs and answer all your questions.

Your Comparison List (you must select at least 2 packages)